- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Whether you track backwards in time from the hidden pestilence that is Chernobyl, or forwards from the vengeful terror of Stalin’s collectivisation and anti-nationalist policies, it is an inescapable fact that the Ukraine has had a bloody and awful century. In the winter of 1932-33 alone some four to five million Ukrainians died in ...

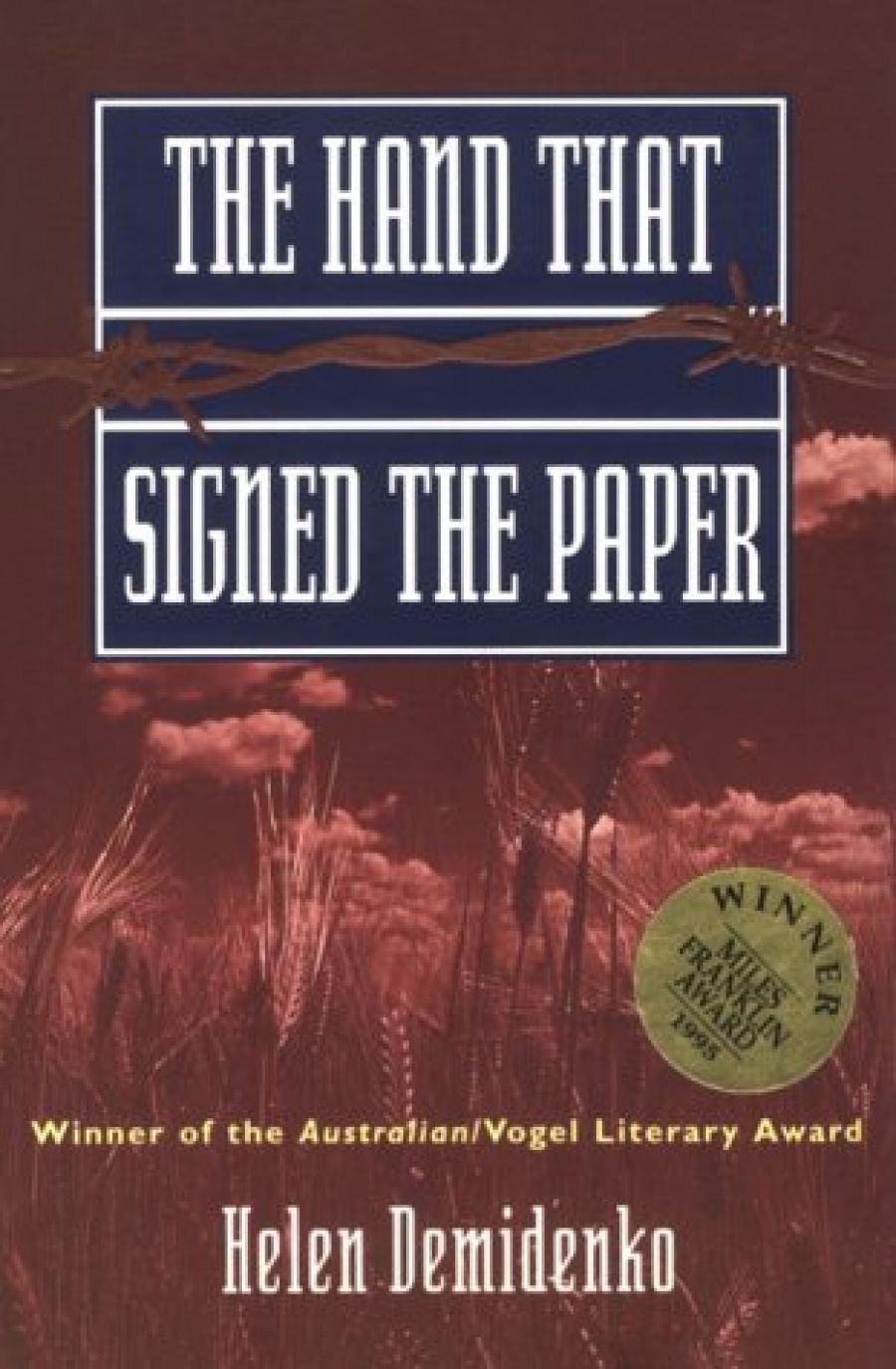

- Book 1 Title: The Hand That Signed the Paper

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $13.95 pb, 1863736549

There is much of this novel that seems to be based on fact, and I wondered whether the main protagonist, Vitaly Kovalenko, might be based on Heinrich Wagner, whose case was not brought to trial because of ill health. There is also, however, much that is clearly imagined, most especially the intimate sexual scenes that strand through the novel. These scenes serve to remind us, the jury, that the characters are made of flesh and blood, and can both love and hate with a passion we would do well to consider when forming our final verdict.

Demidenko argues the case for the defendant well, with great empathy and a profound understanding of the impact of the grand sweep of history on the individual. The title itself underlines this point of view. ‘The hand that signed the paper’ is from a poem by Dylan Thomas: ‘The hand that signed the paper felled a city ... Doubled the globe of dead ... bred a fever, And famine grew’. The relevance of these lines to the history of the Ukraine is striking. Demidenko’s case can be summarised as ‘Guilty due to extreme provocation’. I have been brutalised, therefore I am brutal. The ‘guilt’ is never denied; there are bald descriptions of Vitaly and others bayoneting Jewish babies, machine-gunning hundreds of Jews and perpetrating other atrocities.

Demidenko further invokes the determinism of historical circumstance with a quote from Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan, which says, ‘In such condition ... there is no Knowledge of the face of the Earth ... no Letters ... continual fear, and danger of violent death: And the life of man, solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short.’ The great significance here is the illiteracy of the Ukrainian peasant, which counterpoints the power of the hand that signs the paper. We are shown that Vitaly is unable to sign the papers that mark his entry into the German army (for which he has volunteered) but must sign with a cross. As jury we have to decide whether an illiterate peasant can be held responsible for his own actions. Here the author is having a bet each way; yes, the man is responsible, his motivation is that he has experienced such brutality and hardship, but no, the man is not responsible, because he is ignorant and powerless. Many a philosopher has agonised over this dilemma, and it is not resolved in this novel.

Demidenko’s sympathy for the defendant, while understandable, has resulted in a rather superficial view of Jews, who are not given the same benefits of authorial understanding as the protagonist. Most noteworthy is the lack of acknowledgment of pre-revolution Ukrainian anti-Semitism. The novel does not argue that Jews might also have been the victims of historical circumstance. It is also true that many Ukrainians were suspicious of Germany from the outset of the War and did not collaborate with it, believing it to be just another colonising nation.

This is a fine novel, both disturbing and challenging, and Demidenko skilfully reminds us that evil did not begin and end with the Second World War. I take my hat off to a writer who can produce a book of this calibre before her twenty-third birthday.

Comments powered by CComment