- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

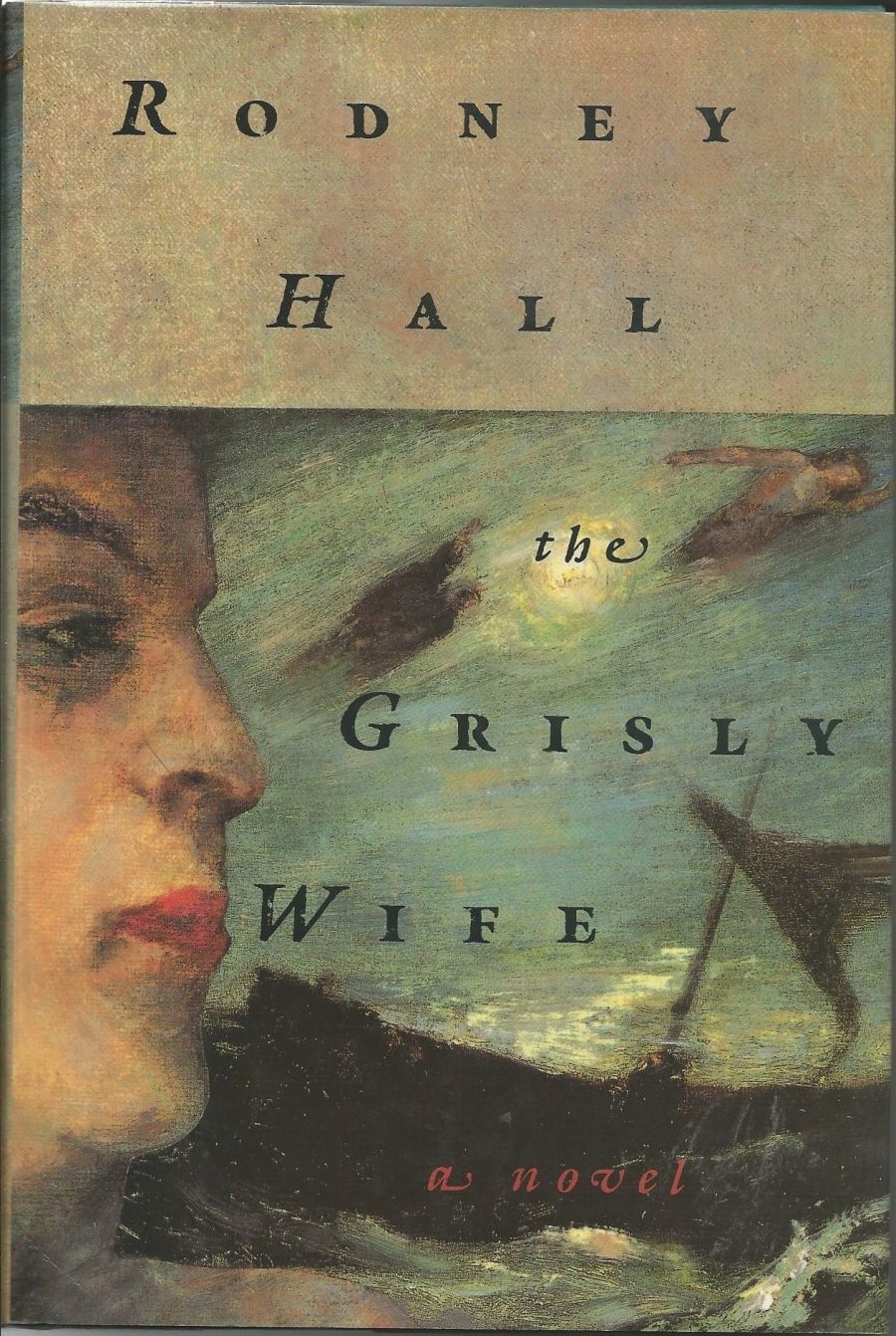

With the publication of Rodney Hall’s latest novel, The Grisly Wife, the author has brought to completion a trilogy that first began appearing in 1988. Since this last published novel is actually the middle work of the trilogy and what were formerly two separate novels are now bridged by this newcomer, we are finally given the opportunity to assess if and how the parts relate to the whole.

- Book 1 Title: The Grisly Wife

- Book 1 Biblio: Macmillan, $35

While the trilogy unfolds across sixty-odd years of colonial life to end on the eve of Federation, this is no mere costume drama or historical pastiche. The geographical location is precise (the territory that Hall himself inhabits on the south coast of New South Wales). But links are not only those of setting or time, or even incident; they are more universal. Hall’s stories deal with the freedom of the individual to act meaningfully, the endless scope for self-deception in human beings, and the coexistence of good and evil. Perhaps most dearly and powerfully it is the subversive effect of myth in a strange land that claims attention. By means of a background of verifiable history and geography we are given an insight into the way that ‘vision’ effects lives.

The trilogy tells us that ‘stories curl round on themselves to bite their own tails’, and this cyclical view of narrative underpins all three novels.

On the surface, The Second Bridegroom is a simple enough story of a young convict’s escape into the bush, his succour at the hands of the Aboriginals and his instigation of the final massacre of most of those in the fledgling white settlement. The Grisly Wife exchanges this attempt to impose a secular order on the Second Eden for a sacred one, with a secret sorority. This sorority, including the ‘Second Eve’, arrives from England in the 1860s to establish a site for the Second Coming. And if the first novel explored what is essentially a male preserve and the second a female one then the third novel, Captivity Captive, is a joining of forces. It is a family novel but one in which internecine warfare, ‘the ferocity of a dosed family’, burgeons into three horrific murders.

Each novel, in fact, ends with a final revelation of murder for which Hall prepares us from the very beginning with more skill and sinister authorial manipulation than Ruth Rendell and company. Hall knows how to lead and excite the expectations derived from one popular genre and then confound them with adroit and admirable literary legerdemain.

However, if the reader’s expectations are confounded this is no more than mild compared to the total overthrow of the world order that confronts the main protagonist in each of the novels. Captivity and freedom, slavery and mastery are at the epicentre of this trilogy so that the escaped convict, the grisly wife, and the usurping son, who feel that they are in all-powerful roles, are finally revealed to be self-dramatising and deluded, supporting players rather than principals: ‘the power of what was being played out in this tragedy went so far beyond me that I had acted as a mere instrument in the conflict without waking up to the fact that I was never my own master in any sense’.

Each of these characters attempts to live and re-enact a myth, to take on some self-imposed mantle of immortality: the Second Bridegroom, the Second Coming, or the Second Fall from Grace. Each fails.

Thus the convict, transported for forgery, finds the whole of his new existence a forgery itself: ‘an outpost of stone and shingles like any little English port (forgery), its church a smaller copy of the very church you were baptised in (forgery), the citizens on the street respectable in full skirts and frock coats (forgery)’. But even more than this is the realisation that as a ‘King’ among the Aboriginals he is powerless, he is the still centre who can only initiate violence without participating in it. The one act of murder he attempts, the murder of another convict, is utterly confounded. And when he tries to import and initiate a fertility myth remembered from his Irish childhood that too becomes a forgery, a fatal inversion in this land of contraries.

The world of The Grisly Wife is seen to be equally bankrupt when its new arrivals attempt to impose another vision on the land. Catherine Byrne is one of a number of women, all physically impaired in some way, who follow a charismatic prophet (actually a deluded and pathetic man) into founding a select colony to welcome the Second Coming. Catherine comes to believe that she is re-enacting the Virgin Birth and is the chosen vessel for the new Christ. A much more mundane explanation of her pregnancy is finally offered.

The third, and perhaps the most powerful novel, is a reworking of the infamous and unsolved Gatton murders of 1898. For the devotees of mystery this is no romantic Hanging Rock scenario but a real-life murder of two sisters and a brother.

Pat Malone is the third of our outcast protagonists, again a witness and initiator but not a principal actor in the murders. He claims the killings become an empowering act, a sacrifice, which ‘broke’ his father’s power and made a heroic claim on God’s personal wrath. With the philosophy that he is better damned than dismal, Pat asserts: ‘my view of life has been cast on a huge scale by the sin I committed against my own blood’. This pathetic attempt at self-dramatisation convinces only him.

The Malone farm, ironically named ‘Paradise’, establishes Hall’s imaginative vision of coastal New South Wales as more Gothic even than William Faulkner’s Yoknapotawpha County. Pat’s father, literally a giant of a man, is God in his own small kingdom, ruling by fear and violence. Pat would usurp him by first bringing the erotic and incestuous tensions of the household to a climax and then donning the (false) mantle of a murderer:

In the world of our sty, in among the real pigs which we were, ran the squealing squabbling piglets we gave birth to: butting greedy little appetites, the clatter of jealousies on trotters that might one day be chopped off, stewed, and set cold in gelatine for a polite picnic lunch at the races, tiny clenched brains and pumping hearts to be grilled for breakfast or stuffed and baked on festival days. Even while we bowed out heads at the big table for Pa to say grace, the floor squirmed with lascivious snufflings and nips, the brush of a sprung flesh tail against your bare leg, the odour of insatiability and the wild confusion of an equality in squalor. The respectable silence of beasts devouring a beast above the board floated thick as oil on the pandemonium of what was being stifled below.

Pat’s self-categorisation of himself as an ‘angel’ has no other authority to back it up and his fall from grace is hardly cosmic enough to label it a Second Fall. In striking at the domestic god, Pat is overwhelmingly ambitious but he is not a heaven-scaling Satan as he would like to believe.

Is any redeeming insight finally offered into these three and the deaths they witness, into their doomed search for a heroic and mythic dimension? The convict who believed that ‘there is nothing to prevent our fables taking root here’ is proved totally wrong. The wife ‘trying to make a journey back to the innocence [she] can never find again at home’ is quite lost. It is finally Pat, of all the three, who does articulate a simple yet major truth distilled from his youthful experience: ‘I have come to see that one purpose behind our training in good and evil is so the land, this unimaginable and largely uninhabited continent, can show itself as beyond such littleness.’

Rodney Hall has offered us a trilogy that will resonate in the reader’s mind long after it has been read. If his characters are failures by their own standards they are noble creations in literature and their aspirations and visions are a mighty contrast to ‘the contemptible blandness, the utterly grey indifference and suffocating comfort now fallen like a blanket on the whole country’.

Comments powered by CComment