- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In 1868 John Heaps (alias Muley Moloch), a preacher, self-styled prophet, and trained bootmaker, left England with a group of eight women bound for Australia. Their intention was to set up a mission dedicated to the development of their own perfection and a preparation for the Second Coming of Christ ...

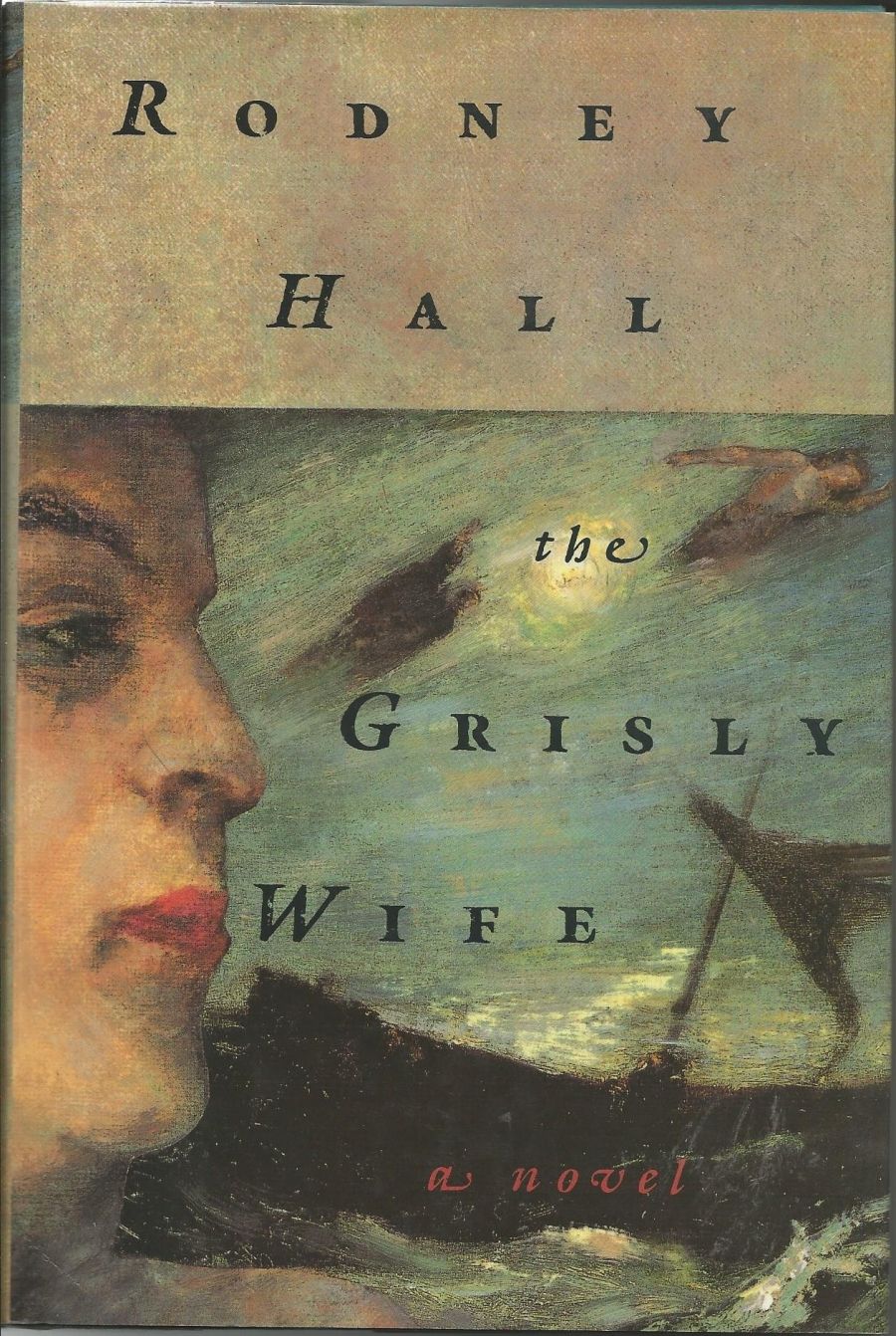

- Book 1 Title: The Grisly Wife

- Book 1 Biblio: Macmillan, $35, 0732907764

The initial brilliance of Catherine Byrne’s narration (the novel is entirely a dramatic monologue spoken by her) gives way to utter ordinariness. After the marvellous vitality and drama of the narrative’s first half – the miracles performed, the storms confronted, the freaks of nature experienced, the hells survived – everything peters out to domesticity, to gestures, to sandwiches and glasses of water.

Hall’s (Catherine’s) stunning descriptions of mid-nineteenth-century sea travel and shipwreck, the workings of a Boschian tannery, a consumptive’ s near-death delirium – and a scene where you will believe a man can fly (or you will believe a woman can believe a man can fly) – all occur in the novel’s first half. The incredible energy of these descriptions is linked to the power Muley Moloch has over the women. They are energised, inspired, captivated by him. He vitalises their universe in a violent, dramatic, seductive way. They believe his miracles (and so does the reader). Under his influence, Catherine is inspired to see the world with a transcendent vision.

But in its second half Catherine’s narrative questions Moloch and itself (once he shows interest in another woman). It is hinted that all the marvellous drama may be tricks, theatricals, a seduction of gullible imaginations and faiths by mere words, by lies, by salesmanship, by sleight of feet. The gloss dulls on the bootmaker/prophet, on the mission, on the hope for the Second Coming, and on the narrative itself.

Then the bombshell. The virgin birth was not a virgin birth. At least that is what the prophet subsequently claims. God didn’t do it at all! It was Muley Moloch himself! He raped his virgin wife while she was in a delirium, practically dead from consumption, and having hallucinatory visions of the production line in a tannery!

This really takes the shine off Muley Moloch’ reputation. Not surprisingly, the women are inclined to turn against him.

The triumph inherent in the proto-feminist discovery by the last two remaining women, Catherine and Louisa – the discovery being that the women’s freedom had lain all along in each other, not in the centrality of the male – is acknowledged appropriately with no fanfare, no epiphany. The sense of this discovery simply trickles into the narrative. No storm. No phallic fireworks. No Boschian blood and guts. Major events keep happening (murders, the runaway son) but these are glimpsed only in the peripheral vision.

In fact, just when you think Catherine has lost the plot, has ground to a halt, has become boring and arbitrary and disjointed in her storytelling, has begun describing in cardboard cutout terms, you realise (or at least I did) that the narrative has done a Moebius loop, has metamorphosed into another sort of discourse. It has lost impact, but gained an undercurrent, a covert strength, a different kind of convincingness.

The significance of Catherine and Louisa’s discovery that their freedom is to be found in freedom from the supervising, censoring, centrally directing, supposedly miraculous male is a quiet miracle in itself, considering the times, and the women’s backgrounds and experiences, I suppose.

But I rather liked them all (and the narrative) better when the prophet could fly or make Catherine (and me) believe he flew; when Catherine could defy the elements (and the ship’s stewards) and go out onto the lurching deck in a monster Atlantic storm for no other reason than to feel she is alive; when I, as reader, felt (with Catherine) nausea in the stinking tannery or suffocation by consumption or deathly fear watching a shipwreck or astonishment seeing a drowned woman brought back to life or delight that the Messiah was kicking.

And I rather fancy Rodney Hall liked them better then too.

At the end, Hall allows Catherine to admit that the seductiveness of the recklessly inspiring and the fabulous has not been entirely wiped out of her: she expresses a final hope that her son Immanuel (now approaching thirty) might still be the Messiah.

So here is another novel set last century that constructs Australian experience out of disasters and miracles and unsatisfactory male-female relationships. I wonder why? We certainly don’t have the miracles anymore these days.

Comments powered by CComment