- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘Singing the Snake’, the poem that opens this collection, tells the story of tribes gathering at Uluru in a time of drought when ‘people drank sand’. If the singing of the people was strong and true, the Snake of Uluru would push water out from the ‘place where every river in the world begins and ends’, so that it spilled from the top of the rock.

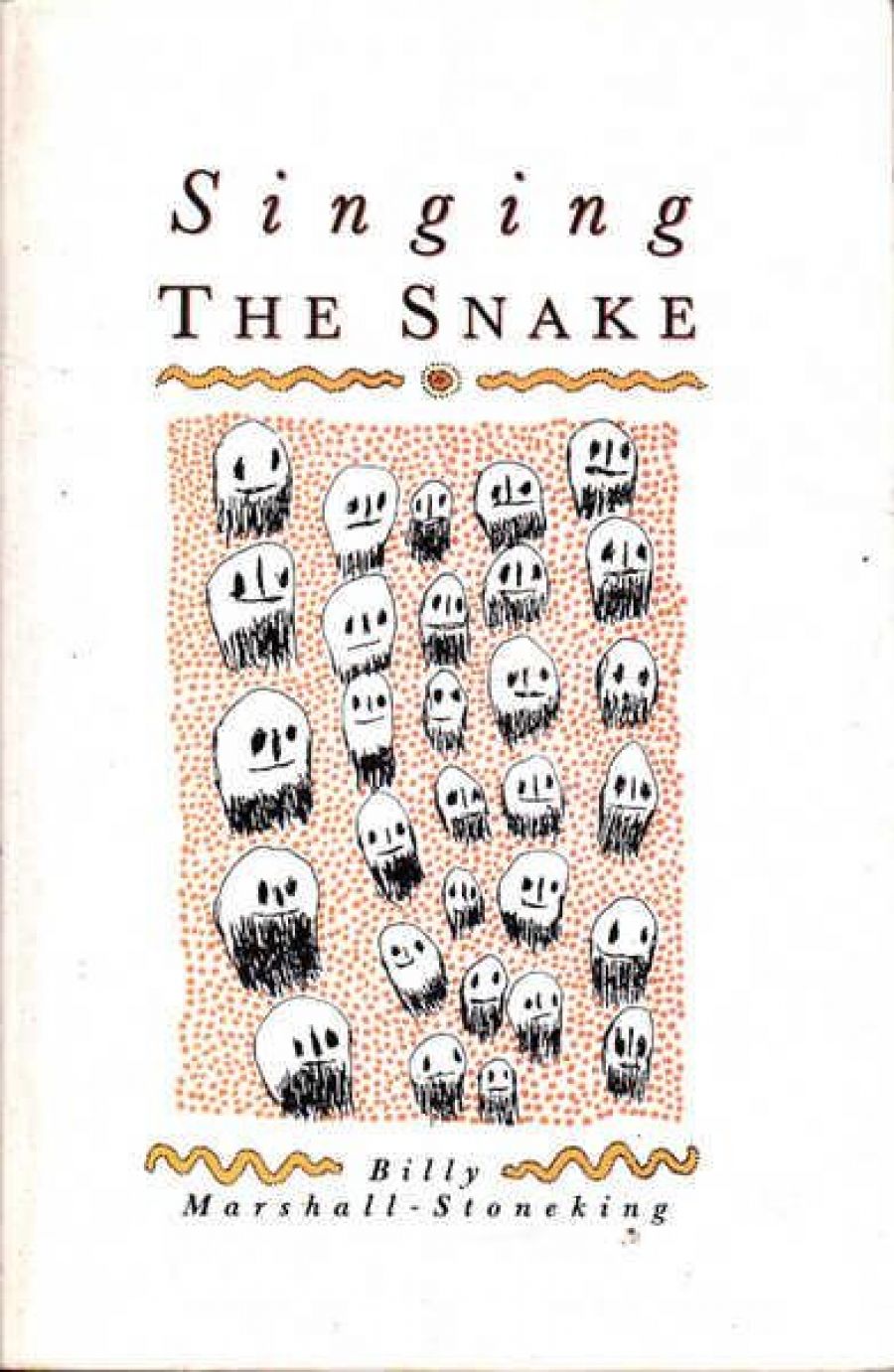

- Book 1 Title: Singing the Snake

- Book 1 Biblio: Angus & Robertson, 97 pp, $14.95 pb

Billy Marshall-Stoneking’s poetry comes from the centre of our continent, and at the same time from the distant edges of a once flourishing Aboriginal culture. He has listened to the Aboriginal voices of the desert and, rather like Melbourne’s PiO, he is intent on finding the mystery of poetry within the voices of a displaced people. But where PiO speaks from within the cafe culture of Greeks who find themselves in a hostile and alien land, Stoneking is the twentieth century Whiteman looking in at the decimation and dislocation of an annexed culture:

On Tuesday he comes to me and wants twenty dollars. I give him ten. He goes away.

The next day, oh, maybe little bit of ten dollar again.

He takes it and goes away.

On Thursday, meat and two oranges. Friday: one tine of tuna ‘pish’ & halfa bag ‘potate’.

Oh anyway!

He says he’s ‘pension’;

he calls me a ‘million’.

On Saturday, five dollars is lousy.

I’m a ‘mean bugger’.

It says much for the strength and confidence this poet has in his work that he can carry off humour in situations such as this without bringing any patronising or dismissive tones into the poetry. There is always a driving force of intense interest in Aboriginal culture and compassion for people in his writing.

The poems sometimes have the quality of ‘found’ art pieces. He discovers for us the poetry of English handled as a foreign object: ‘Everyone is living close to clothes.’ There is a wonderful list of the flotsam thrown up by our culture as it confronts the Aboriginal world:

Before camp pie and shoes

before motor car and Jesus,

before missionary and baby money,

before mining company and police,

before rifle and English,

before guitar,

before card games,

before the Queen …

There are examples of work produced in the process of ‘schooling’ aboriginal children. From ‘Tjungurrayi’ s Werd Book’ we have:

fill in the blanks: …

We will play

need and seek

a tray of

days

I have ten cents

to cry

Perhaps this unadorned presentation of voices and incidents is the only honest approach a white poet can take when his material has been found at the grotesque price of slaughter, disease and poverty. The stories that seem to be taken down verbatim here often have the same simplicity and force of the stories recorded by Steven Hawke in Noonkanbah. They stand not as part of a history, or a political argument here, however. They stand as poems – poems presented as literature to readers who are perhaps not prepared for the raw accusations of some of these stories:

Whitepella bin go round n round for nothin

night n day

bring em here

old people pinished!

very bad trip

flour, clothes, suger

eat em long –

kill em tinna corn beef

There are other poems which seem to re-fashion and re-tell Aboriginal myths, often conception myths. These are fine, simple poems, but perhaps the disservice they pay to these beliefs is that we cannot comprehend them as more than anthropological information, or ‘poetic’ stories not far distant from Charles Kingsley’s stories of the water babies. It seems that reader and writer can only flounder at this point. Where poetry might have seemed a rhetorically powerful place for the verbatim stories, it tends to prettify the religious stories.

Most of the time Stoneking effaces himself as a presence in these poems, in order to focus on the voices and stories of the desert people. But he cannot of course remove himself entirely, and the fragments of talk and events are selected with strong political and social concerns for the rights and for the tragedy of Aboriginal people. He does this, as an outsider, at his own expense. His is the task of the translator, the scholar, the editor, one who passes on what might otherwise be lost, passed over, or never understood.

Comments powered by CComment