- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Eye am an other: (or Eye and Mee talk about their phobias)

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Fictions about academic life have always been about sex, but these days the sexiest thing to write about is theory. Fortunately for the writer who wants to write about both sex and theory, the equation between sexual and textual intercourses has excellent credentials in the poststructuralist canon. Followers of Barthes and Derrida have taken to the pleasures of the theoretical text with an eagerness aptly defined by the sexual metaphors they overindulge in. Others, less enamoured by theoretical discourses, have found that these provide an excellent target for parody and satire, and thus manage at once to partake in the playful intercourse and retain a critical, mocking distance. What tends to be forgotten, amidst all this textual cavorting, is that literary theory is a reasonably rigid intellectual discipline: playful though it may be, it is easy to get it all wrong!

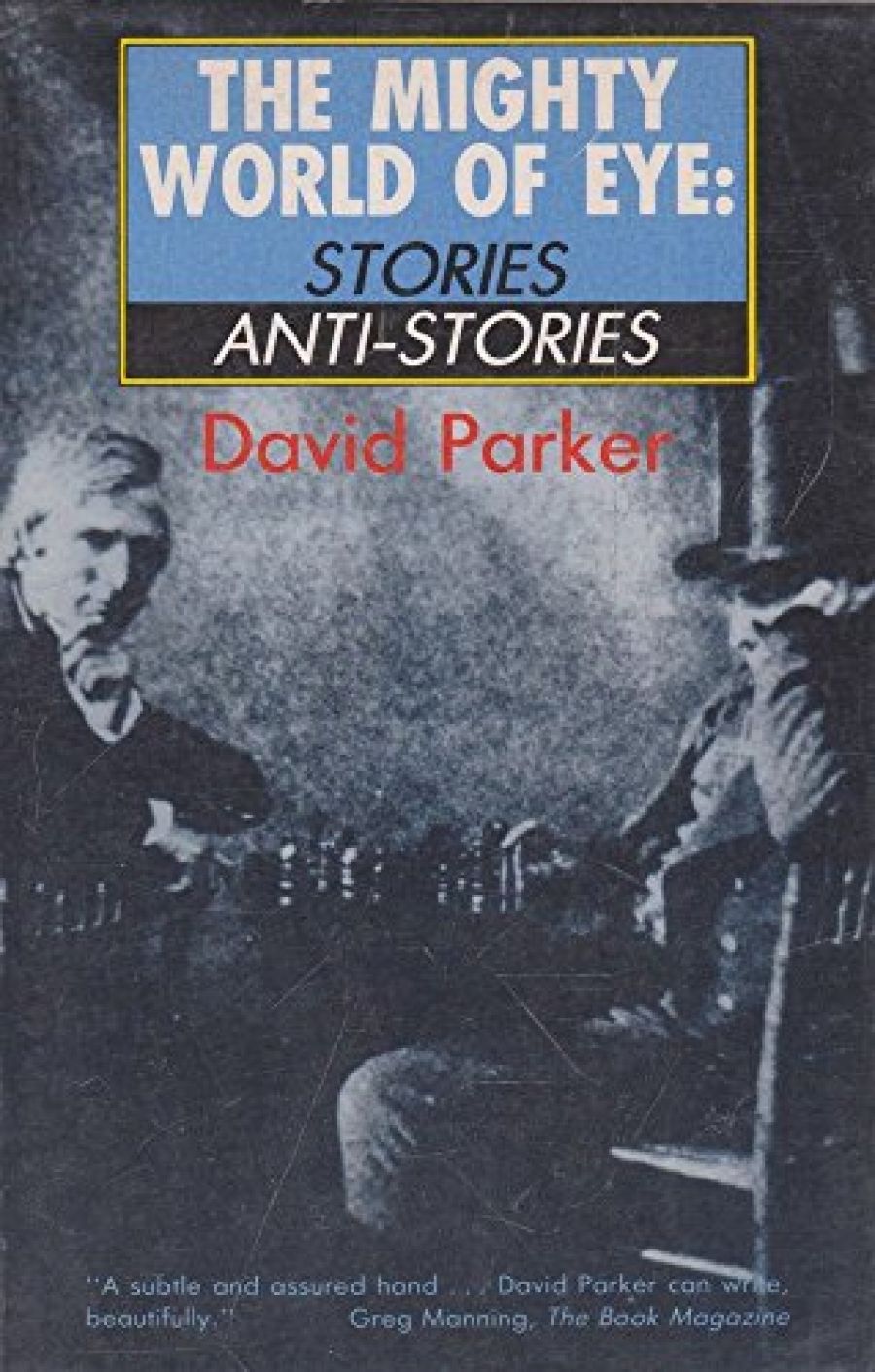

- Book 1 Title: The Mighty World of Eye

- Book 1 Subtitle: Stories/Anti-Stories

- Book 1 Biblio: Simon & Schuster/New Endeavour Press, $16.95 pb, 194 pp

The stories end on a revelation: the reader (and occasionally Roly himself) gets access to (or at least a glimpse of) the true nature of his situation. A well-rehearsed and perhaps dated recipe for short fiction, but it is a recipe that works well in most of these stories. Roly Eye is the kind of character one can both laugh at and identify with, the stories are often amusing, sometimes touching, and told with a keen eye for the trivia and revelations of everyday life.

Before the reader gets to the stories of Roly and his adventures, however, he/she has to negotiate a complex apparatus of material aiming at discouraging a simple, realistic reading of the text. The person responsible for the shape of the book is not, we learn, the naive author of the stories but his colleague and critic, Arthur Mee. In Mee’s competent hands The Mighty World of Eye becomes a very different kind of text, a critical edition, complete with introductory essays, detailed analyses of each story and, for the uninformed reader, an encyclopedia of poststructuralism. Using every trick of the poststructuralist trade, Mee goes about deconstructing the realist surface of Eye’s fiction and, inevitably, reaches the conclusion that it is transgressive of its apparent meaning. Borrowing a few ideas and many impressivesounding phrases from psychoanalytical criticism, feminist criticism, Marxism and deconstruction, he teases out the fissure of aporia of each text and poor Roly emerges in a sorry shape indeed: phallic inadequacy, phallogocentrism, nationalist homophobia, anglophile xenophobia, empiricism and poststructurophobia, to name a few of his shortcomings.

The fictional web thickens further; Arthur Mee is, in his tum, challenged. The two writers, we learn, are in fact colleagues at the University of Artificial City and the whole textual enterprise is tainted with their personal and professional rivalries. Masquerading as a collection of stories or as a critical edition, the book in fact aspires to be a novel of sorts, similar in structure to Nabokov’s masterpiece Pale Fire, where the creative writer is overshadowed and his text distorted by the paranoid projections of his commentator. Mee’s paranoia (which he projects onto Eye) stems from sexual frustration: he converted to poststructuralism after losing his wife to another poststructuralist colleague. His trendy theoretical discourses serve both as a substitute and as an act of revenge. In the end it is Roland Eye, for all his limitations, who is seen in the most sympathetic light, and fiction of the realist, humanist tradition is valorised over the various ‘transgressions’ currently in vogue.

What worries me in all this, is that we are never quite sure who or what is exposed to ridicule. Arthur Mee is obviously a caricature of the halfbaked poststructuralist critic, and anybody who has been around literature departments in the last ten years or so will recognise the type (or think they do). And yet it would seem that Parker’s mockery includes poststructuralist theorising itself, along with the reading and writing practices it has inspired. The problem is that poor Arthur is so hopelessly inadequate, both as a critic and as a theorist, that it is difficult to take this part of the parody seriously.

His deconstructionist ‘fissure hunting’, when it is not simply wrong, generally amounts to nothing but translating into poststructuralist jargon what any reasonably perceptive reader would have realised, and his knowledge of theory seems restricted to the commonplaces listed in his ‘brief encyclopedia’ (where Derrida gets an eight-line entry). He even commits a capital offense against his own credo by confusing Roland Eye, author of the stories, with the main character of each story (who, in Eye’s original version, did not carry his name) and interpreting each text as barely disguised autobiographical writing. The further assimilation of author and critic (EyeMee) could be seen to reflect the divided self of the book’s real author, but how that is to be interpreted in terms of parodic intentions, I am not quite sure.

The meta-theoretical dimension of Parker’s text, for all its inventiveness, remains problematic: it is not quite funny enough for the book to be read as an academic comedy a la Lodge or Bradbury (who also uses theory to write against theory), and its account of poststructuralism is so sketchy and distorted that it hardly amounts to a serious attack. Pace Mee, I, like Eye, refuse to believe that the literary climate at present is such that good conventional stories have to be revamped in pseudo-transgressive garb in order to seduce the reader.

Comments powered by CComment