- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Cultural Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Trio of sorts

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

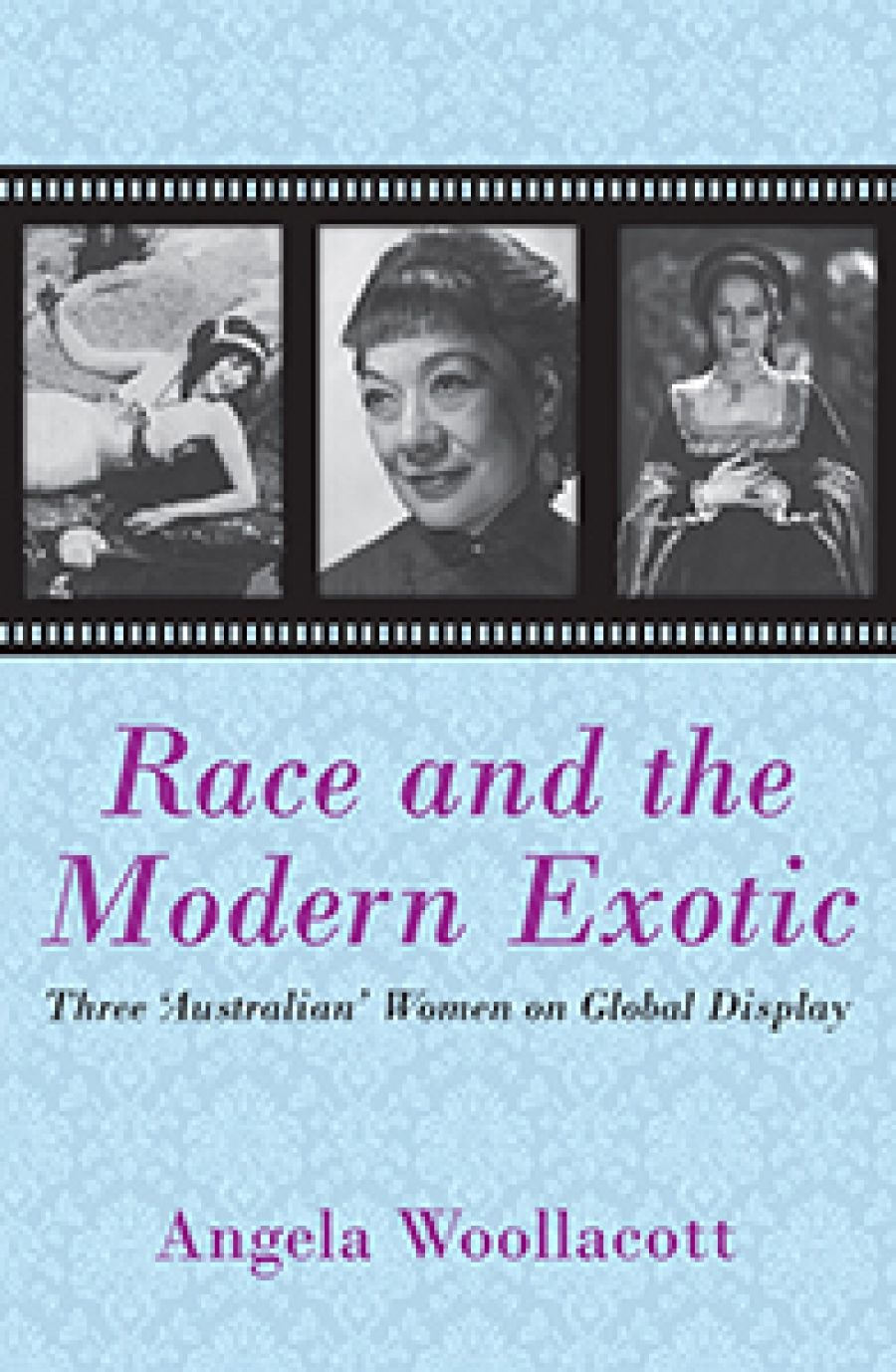

Annette Kellerman, described by Angela Woollacott as ‘swimmer, diver, vaudeville performer, lecturer, writer and a silent-film star’, has been rediscovered in recent years. In 1994 Sydney’s Marrickville Council renamed its Enmore Park Swimming Pool, upgrading it from a humble pool to the Annette Kellerman Aquatic Centre, in honour of the international celebrity, who briefly lived in the neighbourhood as a small child. A 2003 documentary by Michael Cordell celebrated ‘The Original Mermaid’. Now Woollacott presents her, in the company of two other performers, as creating ‘newly modern, racially ambiguous Australian femininities’. Her sisters in racial ambiguity are none other than film star Merle Oberon, whose claim to have been born in Tasmania began to be debunked not long after her death in 1979 (hence the inverted commas necessary for ‘Australian’ in the subtitle), and Rose Quong, performer and writer, whose fascinating story will be unknown to most of us, and is the real discovery of this book.

- Book 1 Title: Race and the Modern Exotic

- Book 1 Subtitle: Three 'Australian' women on global display

- Book 1 Biblio: Monash University Publishing, $24.95 pb, 154 pp

Born in 1886, Kellerman was encouraged to take up swimming as a child to help strengthen her legs which had been affected by rickets. She showed a marked proficiency in the pool and was soon competing in some of the first swimming events for women. From the beginning, her father saw her potential as a performer, and as early as 1903 she was giving a ‘diving exhibition’ at Melbourne’s Theatre Royal. As she took control of her own career, Kellerman began to see the potential of, as Woollacott puts it, ‘a shrewd use of the possibilities of the mass entertainment industry’. Her five-mile swim down the Yarra in 1905 attracted publicity and served as a preparation for the more challenging swims she would make in Europe later that year. After Kellerman’s thirteen-mile swim down the Thames and a twenty-two mile race down the Danube, the London Daily Mirror sponsored her first unsuccessful attempt to swim the Channel. Two further attempts, though unsuccessful, served to keep her in the public eye. She was, then, already a sporting celebrity when she made the transition to the vaudeville stage. She was tireless and astute in diversifying the act that she later took to the United States, adding dance, singing, tight-wire walking, and even male impersonation inspired by Vesta Tilley’s ‘Burlington Bertie’. She was soon dabbling in the infant movie business, and in 1914 made her first major film, Neptune’s Daughter, set on a South Sea island. Now a public figure, Kellerman rated a mention in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s This Side of Paradise and attracted the attention of Jack London.

It is the association of swimming with idyllic South Sea island settings that leads Woollacott to probe the extent to which Kellerman’s films drew on ‘racialised imagery’, though she concedes that the connection is loose. It is as if the primitive exoticism of the South Seas seemed a suitably scenic and romantic location for a not very serious film featuring swimming and diving, whereas there is little evidence of ‘racialised imagery’ playing much part in her stage act, with the limitations imposed by the water tank. What dominated all her performances and publications was the modernist promotion of women’s health and fitness, which provided the context and justification for the daring one-piece swimsuit she wore and promoted. She was billed as ‘the perfect woman’, her measurements advertised as being almost identical with those of the Venus de Milo.

Chinese-Australian Rose Quong did not enjoy Kellerman’s kind of success and fame, but her career was, in its way, just as striking. Born in Melbourne in 1879, Quong developed an early interest in Western literature and theatre; she competed in elocution competitions and gained a reputation in amateur theatre. Shakespeare was her passion, but such roles eluded her; on the other hand, her ‘Chineseness’ did not prevent her being cast in ‘European’ parts. She was praised for her performance as Everyman in the English morality play, and here, as with other plays she appeared in, it seemed as if, for reviewers, her acting was so impressive that her being Chinese became irrelevant. However, in Australia she never ventured into professional theatre. Woollacott does not speculate as to the reasons for this, but evidence suggests that Quong’s job in the public service may have been necessary to help support her mother in the wake of the death of her father.

It is remarkable, surely, that Quong was a mature forty-four when she made the journey to England to embark on a new career – ‘my great adventure begins’, she wrote in her diary – and, though it was not her intention at the time, she was never to return to Australia. In England, and later in America, she gained some stage work, most notably appearing with Laurence Olivier and Chinese film star Anna May Wong in The Circle of Chalk, an adaptation of a traditional Chinese play (though according to Olivier, in Confessions of an Actor, the production was a flop). But Quong soon realised that on the professional stage her Chinese appearance was going to limit the parts available to her, and she radically altered the direction of her career, drawing on her Chinese background to give lectures that became ‘costume recitals’ on topics such as ‘The Culture, Wit and Wisdom of China’. As interpreter of the East to Western audiences, Quong’s new theatrical persona was, Woollacott suggests, exotic rather than erotic, distinguishing her, say, from Anna May Wong. Yet there was an erotic ambiguity to her stage presence: Gertrude Johnson told her that her voice sounded sexless – ‘too deep for a woman’s and too soft for a man’s’. It is perhaps appropriate that at the age of ninety-one, when she made her only film appearance in the Canadian Eliza’s Horoscope (1975)with Tommy Lee Jones, she was cast as herself, Rose Quong, ‘Chinese Astrologer’.

In a way, the Anglo-Indian Merle Oberon does not belong in the company of the Australian-born Kellerman and Quong, but Woollacott is primarily concerned with showing how Australians ‘participated in the construction of Merle Oberon as Tasmanian’, though of course they had no reason to doubt the life story that she and the studio had provided for them. It is hardly surprising that Australian fans took huge pride in Oberon becoming a Hollywood star. If there was a whiff of racial anxiety when she was cast as the Japanese wife of a naval commander in The Battle (1934),Woollacott argues that her ‘imagined Australianness trumped any such worries’. They were not to know the anxiety that Oberon herself experienced about her Anglo-Indian origins: she was sensitive to any suggestion that she was ‘exotic’, with its sexual connotations, and for a time she used a common bleaching cosmetic which would cause her skin problems. During her first visit to Australia in 1965 at the invitation of Qantas, she was uneasy when asked about her birthplace, and started randomly to vary the story. Charles Higham, later to co-write a biography of Oberon (Princess Merle, 1983), interviewed the film star and found her ‘distracted, frightened, and anxious to get home’. A visit to Hobart in 1978 was even more traumatic. Speaking at the civic reception accorded her, she broke down and had to leave the room. The irony is that when the truth about her Anglo-Indian background, with the documentation of her birth certificate, emerged, there were many in Tasmania who refused to accept it, and to this day claim to have evidence for their version of the Merle Oberon story.

If Oberon felt compelled to live with her painful secret, she at least had the considerable compensations of stardom. Rose Quong began by ignoring her Chineseness, feeling the pull, as so many Australians did, of the metropolitan culture. But, when faced with the realities of making a career on the English stage, she turned to exploiting her Chinese identity in order to eke out a modest living. Annette Kellerman, on the other hand, was secure in her racial identity – and I don’t think Woollacott fully acknowledges this – so she could draw on South Seas imagery on her own terms.

The title of Angela Woollacott’s book suggests that it is aimed at an academic or student audience. The narrative is laced with terms such as ‘gender transgression’, ‘hegemonic whiteness’ and (my favourite) ‘the transnational marketability of Orientalisms’. While the theoretical framework is necessary to a study such as this, some of the jargon does distract from the experiential reality of the three life stories that form its basis. Nevertheless, Race and the Modern Exotic succeeds in illuminating the difficulties faced by these talented and courageous women performers in negotiating the complex interaction between racial identity and sexuality.

Comments powered by CComment