- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

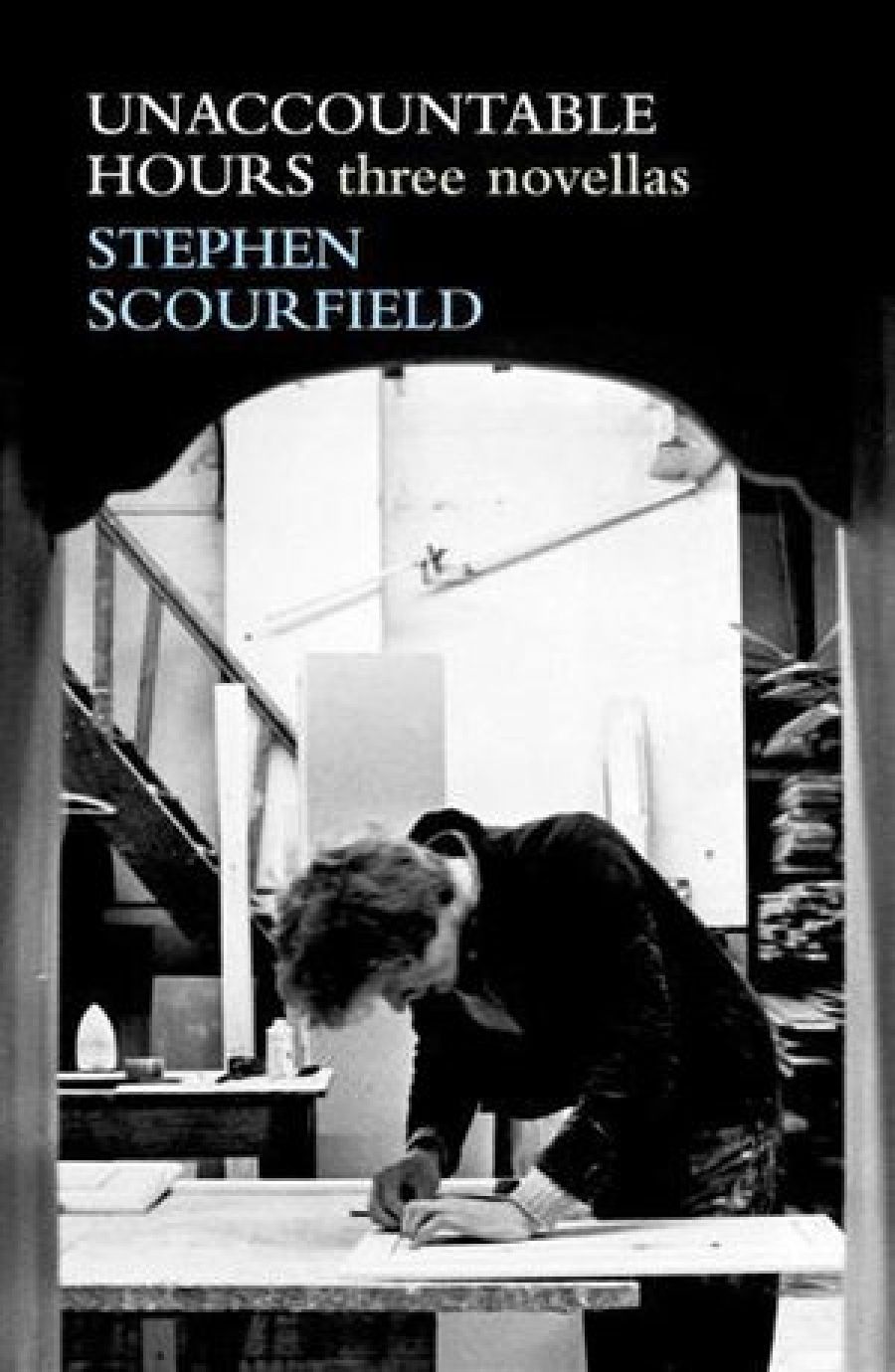

- Custom Article Title: Elena Gomez reviews 'Unaccountable Hours' by Stephen Scourfield

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Solitude is a wonderful enabler of art, but as we learn from Stephen Scourfield’s stories, it can engulf us in the absence of external balancing forces and can become dangerous in the process. Each of the characters in Stephen Scourfield’s three novellas (a craftsman, a novelist, and a student of nature) is a solitary, with the possible exception of Bea, the septuagenarian companion of Matthew Rossi in the second novella, Like Water, who is slightly more inclined towards relationships than Matthew, who says of his ‘fistful’of girlfriends, ‘In terms of human relationships, the only thing I enjoy more than their company is not having their company.’ When practised by Dr Bartholomew Milner, naturalist and Ethical Man, solitude’s dangers become obvious.

- Book 1 Title: Unaccountable Hours

- Book 1 Subtitle: Three novellas

- Book 1 Biblio: UWA Publishing, $32.95 pb, 352 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.booktopia.com.au/unaccountable-hours-stephen-scourfield/book/9781742583884.html

In Like Water, Matthew is a writer who has divided his life between Western Australia and Rome. Unlike in The Luthier or Ethical Man, we are privy to Matthew Rossi’s thoughts and fears. Also pivotal, and different from the other two novellas, is the fact that this is the only story in which Scourfield allows the reader to be part of the protagonist’s relationship from its embryonic origins. Even married and a father, Alton Freeman’s devotion to his family seemed muted and filtered through the devotion to his craft. But Matthew’s friend Bea is exciting, feisty, and loyal: their friendship is a pure, albeit strange one, given the forty-year age gap. Bea lends a brightness to this story that is not present elsewhere.

In the final novella, Ethical Man, the reader learns that Bartholomew Milner also has a craft. His self-imposed exile into the Western Australian wilderness is a part of it, and while his profession lies in the field of biology and nature, Bartholomew’s true craft is his Ethic. It is this Ethic that informs his secondary passion, science – the crux of his being. In all three stories elder, mentor-like figures prominently in each protagonist’s life. For Bartholomew, his reverend father serves as the cornerstone of his ethical development, and Bartholomew has been an unflinching disciple of this, despite digressing into the Buddhist lessons he encounters as an adult (‘never lie’ is the take-home message). We might, through this vehement condemnation of lying, catch a glimpse of Scourfield’s own ethics – the truth-advocating Buddhist teacher is remembered in Like Water, during a socially awkward moment in which Matthew finds himself.

Bartholomew’s Ethic is a burden, not only in the role it plays in his banishment from the science community – his refusal to stay silent on the controversial topic of the Sixth Extinction sees him discredited and humiliated in the media – but in far graver ways. His Ethic is damaged by its lack of contact with other beings: ‘He had accepted the compromises of this, its impossibility. (He lapsed into the egotistical desire to self-satisfy that characterised his species.) But now it seriously ate into him. Every action and its effect gnawed on him.’ When Bartholomew’s circumstance tests his resolve it becomes a case of him against the land. For all the wailing sands and humbling flora and fauna, his determined solitude prevents us from admiring or empathising with him.

The haunting quality of the Australian landscape that Scourfield evokes, particularly in the ocean (Like Water) and the desert (Ethical Man), is reminiscent of that in his first novel, Other Country (2007), which was set in a similarly other-worldly climate, Australia’s Top End. It is almost as if Scourfield must give us incisively drawn human characters who are able to compete against vivid environments without succumbing to their overpowering presence.

Comments powered by CComment