The Indigenous August issue

Welcome to our Indigenous issue, a major addition to our suite of themed issues. In addition to our usual features, there is a range of reviews, essays, commentaries, and creative writing dedicated to Indigenous history, politics, archaeology, and society.

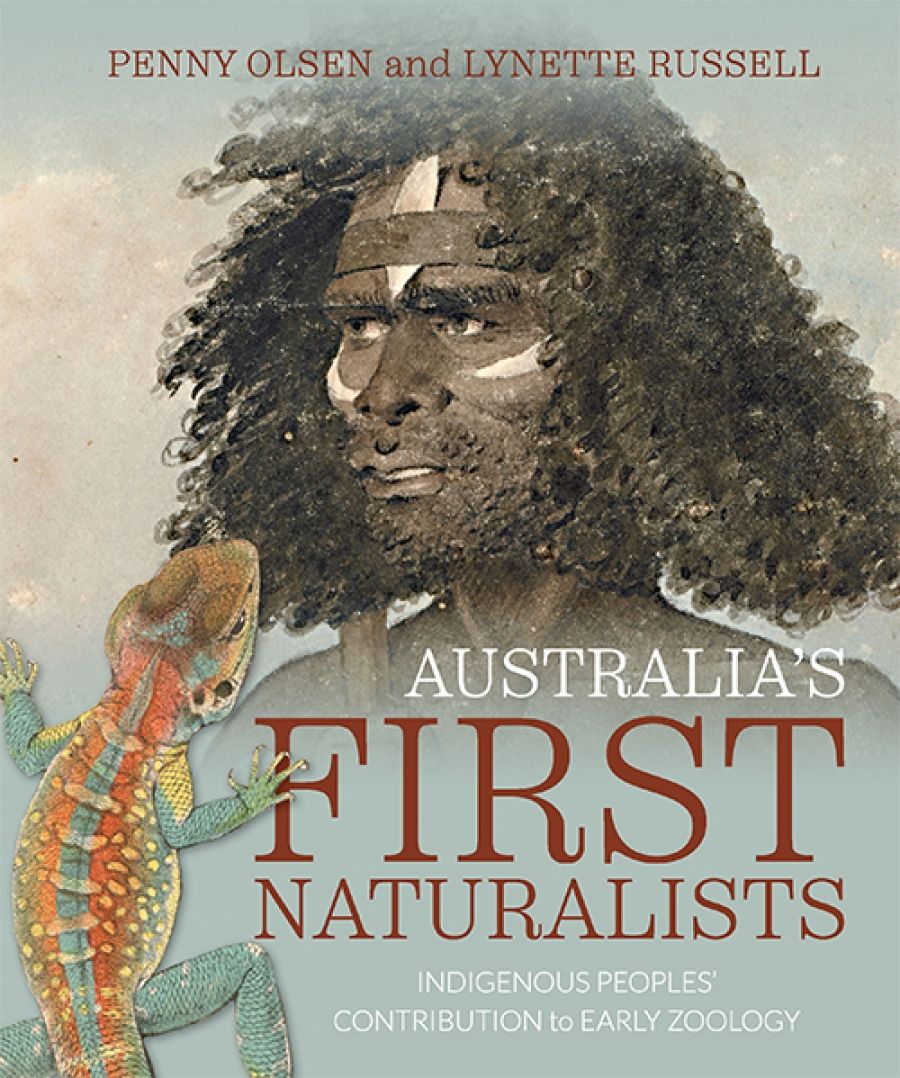

Guest Editor Professor Lynette Russell, Director of the Monash Indigenous Studies Centre, writes for ABR about the ‘efflorescence of Indigenous creative talent’ and the widespread debate about constitutional reform following the Uluru Statement from the Heart. She welcomes the fact that this themed issue – now an annual feature – marks an ‘engaged commitment to true reconciliation and Indigenous recognition’.

Elsewhere, Bruce Pascoe reviews two new books by Stan Grant; Omid Tofighian discusses 'Behrouz Boochani and the politics of naming'; Ellen van Neerven reviews Tara June Winch's new novel The Yield; an interview with Magabala Books publisher Rachel Bin Salleh; Sandra R. Phillips reviews Tony Birch's The White Girl; Deborah Cheetham reflects on 'A Night at the Opera'; and Sarah Maddison and Dale Wandin address the vexed and heterogenous Treaty processes underway in different states and territories.

Announcing the $10,000 ABR Indigenous Fellowship

To complement the Indigenous issue and to explore some of the issues touched on, ABR has created a new writers’ fellowship worth $10,000. The ABR Indigenous Fellowship – funded by our growing number of Patrons – is open to Australian Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander writers, commentators, critics, and scholars. Over a period of twelve months, the Fellow – to be chosen by Lynette Russell, dual Miles Franklin Literary Award-winning author Kim Scott, and Peter Rose – will contribute a series of non-fiction articles on Indigenous subjects.

Those interested in applying should consult the Application Guidelines and the Frequently Asked Questions. Applicants have until October 1 to apply.

'Nah Doongh’s Song'

As noted in the previous issue, Grace Karskens is the overall winner of the 2019 Calibre Essay Prize, as judged by J.M. Coetzee, Anna Funder, and Peter Rose. With Professor Karskens’s permission, we held over her essay until this issue because of the poignancy of the story of this abiding, embattled Aboriginal woman whose life encompassed nearly all of the nineteenth century.

Indigenous subjects often figure in the Calibre Prize, and they always resonate with our readers. (Martin Thomas’s essay ‘“Because it’s your country”: Bringing Back the Bones to West Arnhem Land’, which won the 2013 Calibre Prize, is by far our best-read online feature ever published.) Grace Karsken’s essay is a powerful addition to this growing literature.

The author told ABR:

‘I am delighted to win the prestigious Calibre Prize, and I want to gratefully acknowledge and thank ABR, the sponsors, and the judges. This is also a big win for Aboriginal biography, and for slow history: the time it takes to recover the stories of Aboriginal people who survived the maelstrom of invasion and dispossession with such courage and resolution.’

As we went to press, we were finalising two events to celebrate Grace Karskens’ essay. On Wednesday, August 28, she will be in conversation with Peter Rose at ANU; and there will be a similar event at Gleebooks in early September. Look out for details on our website and social media.

Blak & Bright

The Blak & Bright First Nations Literary Festival returns to Melbourne. This four-day festival (5–8 September) celebrates First Nations writers across many genres, including speculative fiction, oral stories, philosophy, drama, and poetry. Most events will be free and the full program will be available from 5 August.

ABR Behrouz Boochani Fellowship

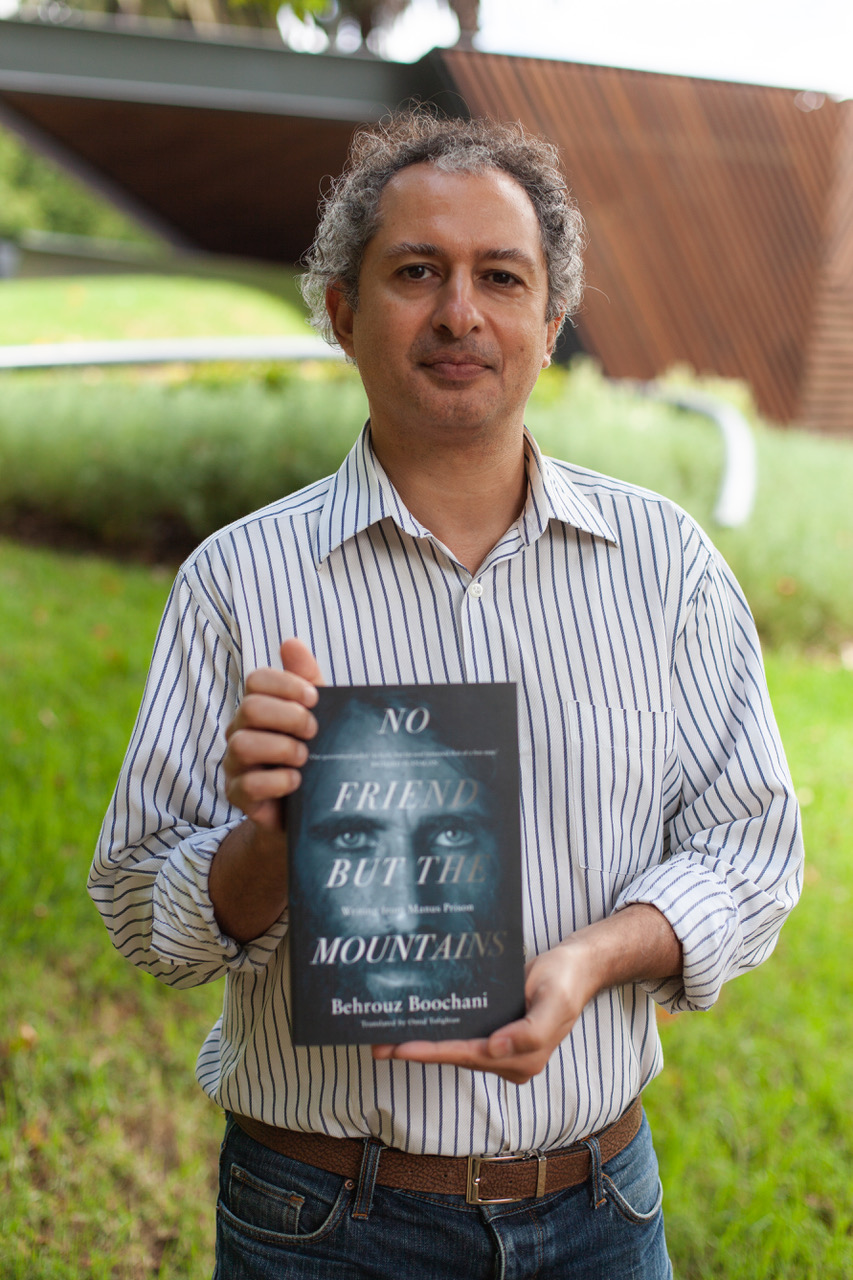

The appalling treatment of Kurdish-Iranian writer Behrouz Boochani (author of the celebrated book No Friend But the Mountains) and the other men imprisoned on Manus Island, Papua New Guinea – and the specious reasons advanced to justify their endless detention – are the source of international outrage.

Despite the obduracy of Canberra and the malign rhetoric of conservative commentators, much is being done to get Behrouz Boochani and his fellow asylum seekers off Manus Island once and for all. To quote Lucy Popescu, writing in the Literary Review (July 2019): ‘The perpetuation of this state of limbo amounts to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment , which is prohibited under international law … to which Australia is a state party.’

ABR is pleased to be part of this international campaign. We were delighted when Behrouz Boochani – for whom the organisation and many of our readers have the utmost respect – permitted us to name our new Fellowship after him. The ABR Behrouz Boochani Fellowship is generously funded by Peter McMullin, a Melbourne lawyer, businessman, and philanthropist, and presented in association with the Peter McMullin Centre on Statelessness at the University of Melbourne. The Fellow – to be chosen by J.M. Coetzee, Michelle Foster (Director of the McMullin Centre on Statelessness), and Peter Rose – will contribute a series of articles on any aspect of human rights, refugees, and statelessness.

Omid Tofighian, translator of No Friend But the Mountains, writes for us in our August issue. ‘Understood as part of other traditions of resistance,’ he says, ‘this Fellowship helps to galvanise a wider dynamic collective process. It has unlimited potential to initiate other projects and actions.’

Let us hope he is right and that this new Fellowship helps to initiate certain actions – and humanity – in Canberra.

Behrouz Boochani – eloquent, impassioned, heroic – has also commented: ‘We need to support writers inside the prison camps and also those people who are recording this history outside the prisons. The Fellowship is … a great step in helping to document the history and to transform the present situation.

The Fellowship, which closes on September 1, is open to English-speaking writers around the world.

Prompter Porter

The Peter Porter Poetry Prize, being offered for the sixteenth time, has been brought forward to separate it from the 2020 Calibre Essay Prize (to be advertised in October). The Prize, open to English-speaking poets around the world, is now worth a total of $9,000, with a first prize of $7,000. The judges are John Hawke (ABR’s Poetry Editor), Bronwyn Lea, and Philip Mead.

The closing date is October 1.

Jolley Talk

Later this month we look forward to naming the three shortlisted authors (and the three commended ones) in this year’s ABR Elizabeth Jolley Short Story Prize. We will then publish the three principal stories in our September issue.

Join us, if you are in Melbourne, on Wednesday, September 11 for the Jolley Prize ceremony (a free event). This year’s venue is Readings Hawthorn. Celebrated author Maxine Beneba Clarke will speak on behalf of her fellow judges (Beejay Silcox and John Kinsella) and will name the overall winner. Full details appear on our website.