- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Anthologies

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This attractive collection of short pieces – mostly fiction – reminded me of the old music-hall adage: start with a bang and leave the best acts till the end. Robert Drewe’s selection certainly begins with a bang. John Updike’s ‘The City’ is the story of a man who arrives in a unnamed city, and sees no more of it than an anonymous hotel room and the hospital where he has his appendix removed. By the end of this cunningly crafted fable, we realise that the city’s fascination for Carson, the central character, is directly related to its being unknown, unseen and as much a cipher (and perhaps a menace too) as it was when he arrived, decidedly queasy from the airline’s freeze-dried peanuts – or so he thought at the time.

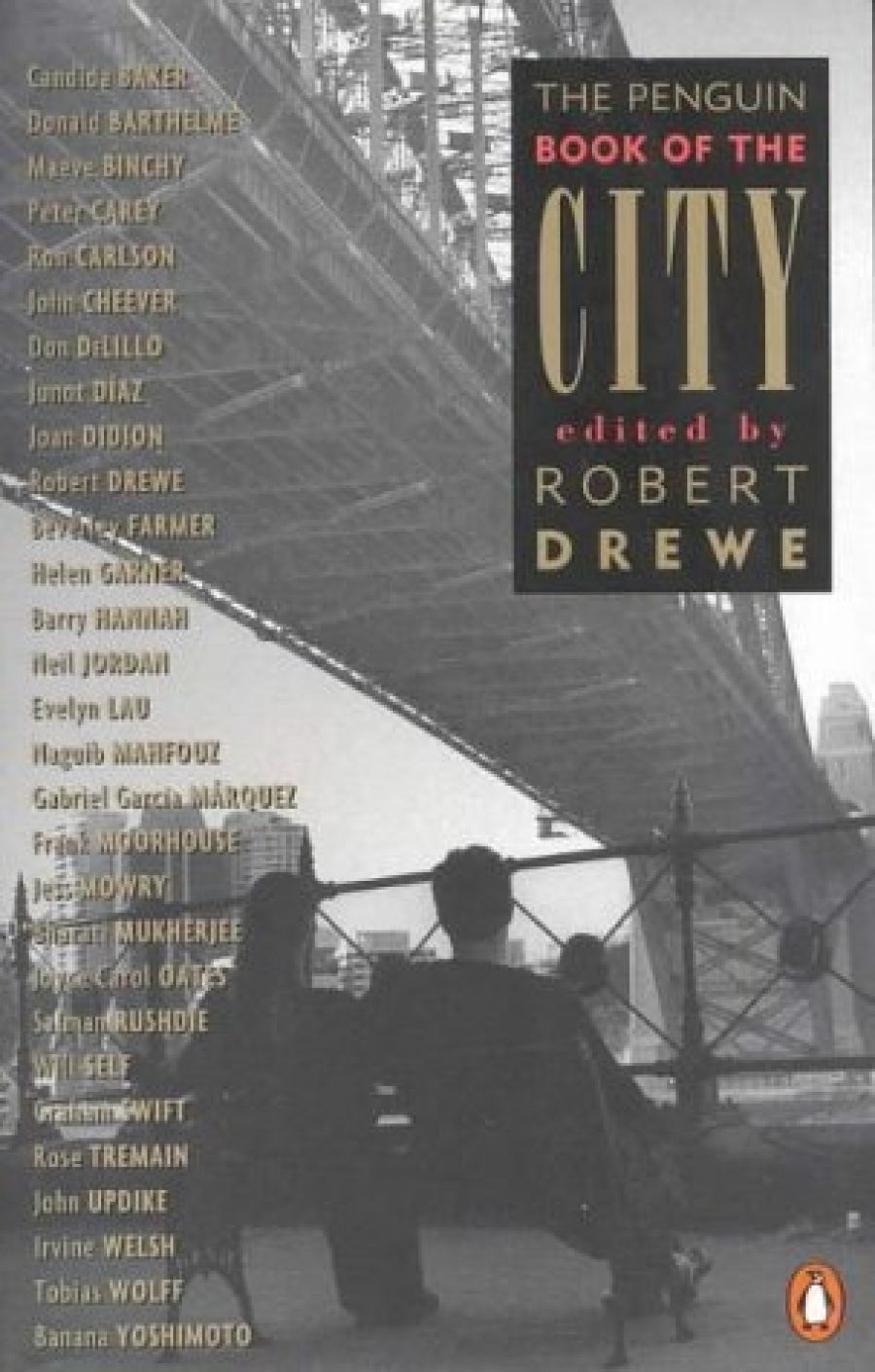

- Book 1 Title: The Penguin Book of the City

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin, $17.95 hb, 382 pp

Several of the best stories in this anthology are also concerned with strangers, visitors and outsiders. Maeve Binchy’s ‘Shepherd’s Bush’ brings a young Irishwoman to London for an abortion. Drewe’s ‘Life of a Barbarian’ is constructed around an Australian businessman who is caught in an earthquake in Tokyo’s Imperial Hotel. Bharati Mukherjee’s ‘Nostalgia’ is a masterly account of how the Porsche-driving, thoroughly Americanised Dr Manny Patel falls victim to his nostalgia for Indian customs, food and women in uptown Manhattan. Peter Carey’s familiar ‘Room No. 5 (Escribo)’ is a strikingly nightmarish evocation of one of those Second or Third World cities racked by rumour, suspicion and the threat of revolution. Graham Swift’s ‘Seraglio’ is a low-key, and for that reason all the more sinister, tale of an English couple’s holiday in Istanbul. On a much smaller scale, ‘Disnae Matter’ by Irvine Welsh (of Trainspotting fame) is an anecdote told in hilarious though almost impenetrable Scots about a punch-up in Disneyland.

The cities (whether real or imagined) in these stories are vivid and menacing because their protagonists are vulnerable and perplexed, as most of us are whenever we find ourselves without bearings. That is particularly evident in Beverley Farmer’s ‘A Man in the Laundrette’ (not, I think, among her most accomplished pieces) in which an Australian woman in New York is troubled as much by the grim enigma of an unfamiliar world as by the man who accosts her in a laundrette. Something of the same deracination colours Frank Moorhouse’s ‘The New York Bell Captain’, a clever if somewhat mannered fable of a man holed up in a hotel room fifteen stories above ‘Fifty-Fourth Street – and the bad end of Fifty-Fourth’.

Those pieces where the characters are in their natural habitats seem to me on the whole less striking, or at least less obvious candidates for inclusion in a volume such as this. Joyce Carol Oates’s ‘Happy’ (‘She flew home at Christmas, her mother and her mother’s new husband met her at the airport …’) does not get beyond the predictable. Naguib Mahfouz’s parable ‘Blessed Night’, the tale of a Cairo drunk who endures a night of disorientation, seems to me to rely for much of its effect on familiarity with Egyptian customs, manners and social structures. Tobias Wolff’s ‘Next Door’ is – if one wants to be pedantic – a suburban rather than a city story: unspeakable neighbours may be encountered anywhere, in towns and townships as much as in cities.

Will Self’s ‘A Short History of the English Novel’ starts very well as a lively tale of a London where every waiter wants to be a writer, but Self does not know what to do with his material, and so falls into cliché at the end. Salman Rushdie’s ‘The Free Radio’ (about, inter alia, the vasectomy campaign in India) is also predictable, as is (in a way) Neil Jordan’s ‘Last Rites’, a powerful, but to my mind overcooked story of a young man who commits suicide in a London public baths.

The last story in the collection provides an exception. Don DeLillo’s recent (1996) ‘The Black-and-White Ball’ is the strong closer, guaranteed to bring the house down. But even in this wry morality tale set among the crème de la crème of 1960s New York very much at home in the ballroom of the Plaza, the focal characters, J. Edgar Hoover and Clyde Tolson, his sidekick, are by their very nature outsiders, eternally suspicious, even when wearing sequined masks and preening themselves before Truman Capote’s friends and hangers-on.

In his introduction Drewe writes that ‘the criterion for selection was simply the personal taste of a professional writer and amateur reader’. There is, of course, no use arguing about taste: Drewe’s and mine do not – could not possibly – coincide. Yet the inclusion of most, perhaps the great majority, of these pieces seems to me justified. I would have left one or two out; but more to the point, I would have welcomed more non-fiction. Some of the best contemporary writing about cities is to be found in essays, journalism and travel books. Certainly, the one journalistic piece in the collection, Joan Didion’s ‘L.A. Noir’ is splendid – I’d give my eye teeth (and a few more besides) to write like her.

Comments powered by CComment