- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘Gordon Jacobs …’ Glass’s voice echoed around the columns of City Hall’s marble foyer as they climbed the stairs to Tuesday Reed’s office. He was as bitter, as irascible and stirred as she had ever seen him. ‘Was your Al, teflon-hearted scumbag.’

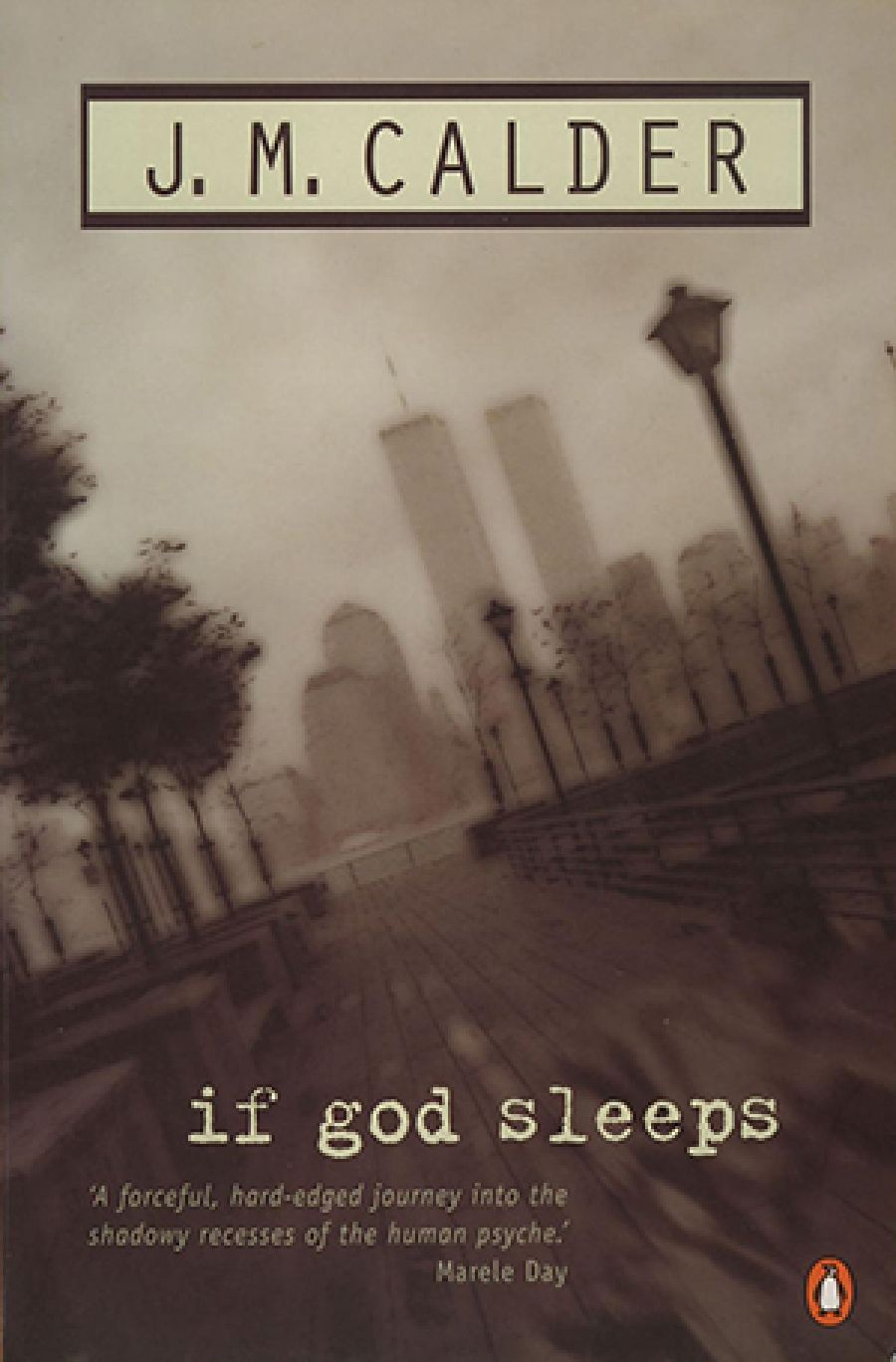

- Book 1 Title: If God Sleeps

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin Books, 357 pp

Instead of stopping at her door, the one with Public Prosecutor stencilled in gold letters across its bubbled glass, she walked past it to the adjoining interview room. She inserted her key in the lock, pushed the door open, invited Glass to precede her.

‘So, two years ago, he rapes a minor.’ Caught up in his own train of thought. ‘Mind if I ..?’ he said, extracting a cigarette from his pack the moment they entered, not really asking or waiting for permission. The entire DA’s Office was strictly nonsmoking. Glass knew this as well as anyone. He’d been counseled before. So why did he do it? Was it a challenge? And why, she thought, did she let him do it? Was it something to do with the strangely agitated state he was in, this pacing energy? That somehow swept her along with it. He hadn’t apologized, part of her was still calm enough to notice, for being late for their appointment. A match rattled against her wastepaper bin.

‘A schoolgirl of fifteen,’ he poured on. ‘And this – ’

‘Scumbag.’

‘He’s got form,’ ticking off the obvious on his thick, powerful fingers, ‘he’s had his warning, he’s had his first stretch, he snatches this bloody kid – ’

‘Fifteen, you said. She’s almost a woman.’

‘That’s funny. I thought the sign …’ He gestured with his thumb back at the door of her office. ‘I thought it said prosecution.’

‘I’m just saying, pointing out. She wasn’t a kid.’

‘What, are you defending this asshole?’

‘I’m not defending anyone. I’m simply saying – ’

‘She’s a kid. You’ve got a kid, haven’t you?’

She let that pass.

‘She’s in her school uniform for Christ’s sake. She’s on her way home. He snatches her, in broad daylight, from a bus stop.’

He stopped, inhaled irritably on his cigarette.

‘She’s terrified.’

‘I know.’

‘You weren’t even here then.’

‘I meant I know how bad - ‘

‘He keeps her overnight on the edge of town in some festering fucking house trailer – ’

‘A fucking house trailer?’ She needed to slow him up, hold off this tide of anger.

‘Oh, very cool, very smart.’

‘Look, I realise you’ve been out all night on this – ’

‘He rapes her, vaginal, anal. What else? Oh yeah, get this – ’

‘Spare me.’

‘And he gets five for his pleasure. Five – with parole after two for …’

‘Good behaviour.’

‘Ri-ight. And we know what a well-behaved little scumbag he is, don’t we? We’ve seen that. We’ve heard from the social worker.’

‘It’s not their fault. They’ve got to – ’

‘We’ve read the psychiatric reports. We’ve heard it all.’

‘The girl hears it all, again. The mother and father are there in the court hearing it all. They’re there for the whole parade. For every beat of the drum. Every detailed ... act. And they learn – you know what they learn? – they learn how this lousy thirty-three-year-old scumbag who’s raped their daughter, who’s given her herpes for life – oh, no, you never get that in the court report, that’s always after, that’s always up to the victim, just to keep her mind on it in case she was ever in danger of forgetting, of putting it behind her and getting on with something that vaguely resembled her life – they learn Scumbag is just a mixed-up kid at heart. That he still bed-wets. That he didn’t get enough love. That he’s desperate to relate … I mean, give me a break.’

‘Wasn’t he on day release? I seem to recall – ’

‘Yeah, and now he’s on permanent release.’

Glass leant down and ground out his cigarette against the side of the bin.

‘We all are,’ he said. ‘Some other scumbag’s gone and done us the favour.’

As he rose, she went to the window and stood looking out over the city. Then she turned and sat leaning against the sill.

‘Still, there’s got to be an investigation.’

He looked at her, now the storm had passed. This was the Solomon Glass she knew. That unnerving, open gaze that held you, weighed you, would not let you look away for a moment for fear of what you might be admitting. It must terrify suspects, she’d sometimes caught herself thinking. That silent, wordless interrogation. Its breadth, its patience. That still spoke back to you. That, even now, was saying: Well, thank-you-Mrs-Reed. Thank you so very much for explaining my job to me. How would any of us poor, half-assed schleps ever manage to stay on the right path if it weren’t for the foresight and the guidance of people like yourself?

Instead:

‘Yes, ma’am,’ he said. ‘Commissioner Keeves has already reminded me of that.’ Reminding her at the same time of who it was he actually worked for. The police and the DA’s office worked together, but not for each other. And she was not his boss. Indeed he saw them as equals – if somewhat distanced, not intimate ones. ‘Unless, of course, something more important comes up …’

‘Like a cat stuck up a tree? Or a stolen bicycle?’

‘We don’t get many stolen bikes up trees.’

‘But you must have something? Some leads, evidence to go on?’

‘One scumbag, leaking through five holes of exactly the same circumference, five slugs, standard Ruger pistol ...’

‘And nobody saw anything?’

‘I hope young Gordon did.’

‘Nobody in the parking lot? It’s hard to believe.’

‘Walk up, bend over the driver’s window, chat with a friend, arm through the open window – it’s hot, Scummy needs ventilation – five soft, round, little messages, phtt, phtt, phtt, phtt, phtt, and lo and behold he’s got all the ventilation he’ll ever need. Walk on, slip into your own car parked two rows away, and off you toddle. Five shells lighter than you came in.’

‘So, how long? Before he was found, I mean?’

‘An hour, maybe longer. A parking officer wants to give him a ticket. Good Samaritan, tries to warn him, wake him.’

‘But he can’t.’

‘He’s not Jesus. He’s handing out tickets, not miracles.’

‘But you must have some idea why.’

‘That’s what he’s paid for.’

She ignored it. ‘Why Jacobs was killed.’

‘I suppose somebody just got public-spirited.’

‘I’m serious.’

‘Look, there’s lots of reasons – you know this as well as I do. One of his asshole buddies, someone he’s crossed, ripped off. He’s into drugs, he’s a street merchant, a courier, he moves property – none of it his own ... It could be any one of hundreds who owes him a shafting.’

‘But he’s on day release. Not many people’d …’

‘Yeah, okay, so it’s someone inside, someone in the system – their side, our side – who spreads the word. That he’s walking on his own power. He can’t go far, he’s got to report, he’s back on the inside for weekends, let’s face it, he’s not hard to find.’

‘Gordon’s gone shopping, the word goes. Someone gets a whisper he admires the deli at Safeway – ’

‘It could be revenge,’ she says.

‘It could be what?’ He looks at her. She is usually smarter than this.

‘No, I mean …’

‘Oh, the goodies – is that what you mean? Mum and Dad, is that what you’re thinking of? Dad’s a lay preacher – did you know that? In the Baptist Church. And Dad – get this, will you? Dad, our new suspect, on the day Jacobs is sent up, writes him a fucking letter, promising to pray for him, for his remorse, for repentance, for his salvation. Can you believe this? You know what he writes? Nobody – I know what he writes because he shows me the letter, he asks me, begs me, to pass it through the system to Jacobs – Nobody, he writes, is beyond the pale of God’s love, nobody should despair.’

‘And did you?’

‘So the next morning, instead of going to church, Dad nips out and buys himself a Ruger, learns from his wide contacts in the criminal underworld where Jacobs is likely to be that day …’

Whatever made her imagine Glass was laconic?

‘He goes to his local supermarket, with a list from his wife for lentils and mayhem, and with five soft little Our Fathers he blows this guy into Kingdom Come.’

‘Did you deliver it?’ It’s the one detail she’s clung to while this wave of invective washed over her.

‘I’m in homicide, Mrs Reed,’ he said coldly, and she realised then how much she’d fear having this man as an enemy. ‘I’m a detective, I’m not a fucking postman.’

And then, more softly, as though suddenly he’d seen himself reflected back from her eyes. ‘Look, Jacobs is dead. We may hear something, we may not – it depends if anyone’s got a private grief they want to share with us.’

‘I suppose you’re right.’ And in fact the simple physical act of reaching for a file on the desk between them, of opening it, was a release. She’d had no idea how tense she’d become. ‘We should get on.’

‘We should. After all, it’s not Gordon scumbag Jacobs you got me here to talk about, is it?’

‘No,’ she said.

‘It’s this other scumbag you’re putting up next week. This Mallick animal.’

‘He’s not convicted yet.’

‘No, but with you leading him through the ring, he will be, Mrs Reed. He will be.’

‘Why, thank you, Lieutenant. Thank you.’

This was the problem with masks. Assembled for defence, they could be flawless, impenetrable. But then, with a small sudden shift, a gesture of unexpected warmth or appreciation, they could crumble, provide no defence at all.

‘I’m pleased I have your confidence,’ she said, but without the irony this time.

And as if in tacit sympathy, his own mask slipped for a moment. And she could see the fatigue in his gaze, hear it in his voice:

‘Well, whatever our differences, Mrs Reed,’ he said, ‘at least we’re on the same side, fighting for the same things. Although sometimes, I begin to wonder why we bother.’

Comments powered by CComment