- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: War

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

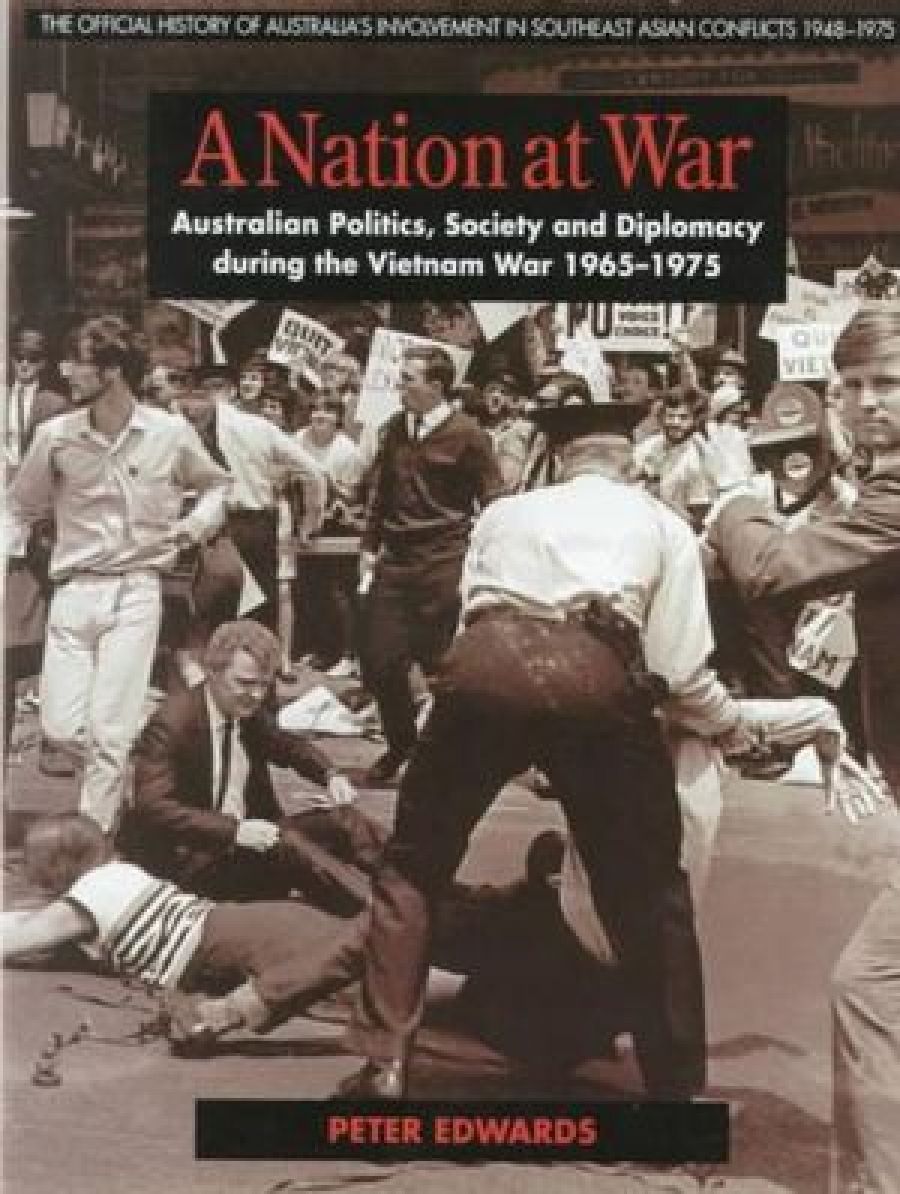

A nation at war is a less than gripping tide, although it is suggestively ambiguous. Australia was at war in Vietnam for most of the decade covered in Peter Edwards’s book. In senses chiefly, but not wholly, metaphorical, it was also a society ‘at war’, divided over conscription and the commitment of troops to Vietnam. The excellent cover photograph illuminates the latter implication of Edwards’s title, as well as the importance of media coverage of both overseas conflict and domestic protest against it. A newsreel photographer looks back into another camera, and away from the policeman who is struggling to shift an inert demonstrator.

- Book 1 Title: A Nation at War

- Book 1 Subtitle: Australian politics, society and diplomacy during the Vietnam War, 1965–1975

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $59.95 hb, 460 pp

The long and lucidly organised narrative of Australian Politics, Society and Diplomacy during the Vietnam War 1965–1975 is the sixth volume in the fourth official history of Australians at war, of which Edwards is the General Editor. He has merged volumes originally intended to be separate, on strategy and diplomacy, and on the home front. The bitter divisions that occurred within the Official Unit are hinted at, but generously elided. Turning to the nature of his enterprise, Edwards avers that:

an official history, written with privileged access to official records, necessarily devotes considerable attention to the actions and motives of successive Australian governments in their policies towards the Vietnam War and in their reactions to the growing popular dissent over the Australian commitment.

Readers should not be discountenanced. Edwards writes a resolutely revisionist history of a period which -although so recent -is often misremembered, if not forgotten. Veterans of combat, as of protest, may have more consoling stories to tell.

While Vietnam was ‘Australia’s longest overseas conflict and the largest and most costly apart from the two world wars’, the outcome was notably unsuccessful for this country. The fall of the Republic of Vietnam was not prevented. Debates over ‘the wisdom and availability’ of Australian involvement in the war, as Edwards notes, have lasted for decades since.

Although in cultural and public terms Australia had its 1960s in the early 1970s (the first Moratorium, for example, was in May 1970), Edwards emphasises how the vital political and social effects of the war had already been felt before the mass mobilisation against it; how the way in which commitment would end had been foreshadowed if not foredoomed.

‘Established groups and organisations’, such as the Congress for International Cooperation and Disarmament, mainly middle class and middle aged in composition, were – says Edwards – the first to express misgivings about the Vietnam policies of the Menzies government. Student ‘demonstrations’ (the unfamiliar word was often in inverted commas) came significantly later. Persistently, Edwards corrects our temporal focus. Television – later credited with contributing to the end of the war with its daily bulletins of horrors – ‘initially helped to endorse the policies and attitudes’ that led Australia there.

The importance of the British withdrawal from ‘east of Suez’ (as directions from the centre of a dwindling empire go) is emphasised. Australian diplomacy was based on the belief that both Britain and the United States needed to be involved in Southeast Asia. The first defection was ‘profoundly unsettling’. When it came a decade later, the American withdrawal was less disturbing. Edwards contends that Australia’s ‘period of gathering alarm’ had in fact come to an end in the late 1960s. Not least reason for that was the fortuitous triumph of anti-communist forces in Indonesia. Australia’s part in the Vietnam War was never solely to do with that country’s travails.

One reads A Nation at War (if old enough) with periodic shocks of recognition, but also surprise. Here is Tom Hughes facing down anti-war demonstrators with a cricket bat; the totemic name of Errol Noack, first conscript to be killed in action; the vile Rigby cartoon of soldiers threatening to bash students at Monash who supported the NLF. The caricature of the servicemen is as odious as that of the students. I had forgotten that South Australian Liberal Senator Hannaford moved to the cross-benches in 1967 in opposition to the government’s war policies and that the New South Wales branch of the RSL expelled Les Waddington for being secretary of an ex-servicemen’s human rights association. State President Sir William Yeo redundantly remarked at the time that the British Commonwealth was ‘a polyglot lot of wags, bogs, logs and dogs’.

Though recent harassment of republican members of the RSL might not lead one to think so, Yeo’s day was nearly done. In his Boyer lectures of 1967, Robin Boyd observed ‘the emergence of an intellectual or cultural opposition to the Australian conservative’. It has existed ever since. In his Conclusion, Edwards argues that their Vietnam policies were ‘disastrous for the conservative parties’ in Australia. Their arrogant assumption of the moral authority was, happily, lost forever, whatever subsequent electoral successes they have enjoyed.

Some conservatives fare well in Edwards’ reckoning. Most surprising among them is Harold Holt, who wrote a far-sighted private letter to Harold Wilson in 1967: ‘There is, I firmly believe, a new Asia emerging, in which we can all find hope for a brighter future.’ On the other hand, Edwards judges, Menzies, Hasluck, and Whitlam all ‘had their reputations damaged by Vietnam’. He extenuates (at least in regard to the first years of the commitment): ‘the issues posed by the war were simply too hard for the responsible ministers and their advisers to resolve’. That gave more of an appearance of duplicity to the conservatives’ actions than, perhaps, they warranted.

Edwards wished to have had room to say more of the role of the States and their police forces, of the media coverage of the war and of US attitudes towards Australian policies. In truth, he deals shrewdly with the latter, especially the appreciation in Washington of Menzies’ early support for intervention, and Nixon’s apoplexy at what he found in Whitlam. Protesters will feel short-changed, but can they fairly object to Edwards’ conclusion that ‘the declining authority of the McMahon government had been matched by the descent and disintegration of the protest movement’? The chimera of an Australian ‘revolution’ has not since seemed imminent. Then, nor has Australia been (in both of Edwards’ senses) ‘a nation at war’ either. With an exemplary clarity, judicious use of sources, talent for compression that looks relaxed rather than summary, he has written a fine book that will enrage many of the stakeholders in Vietnam. That is as it should be. Nostalgia, myth, amnesia will not now be so easy.

Comments powered by CComment