- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Gritty Fantasy

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Awareness of the tension between fantasy and realism in fiction has been heightened in recent years by the trend in young adult novels towards gritty urban realism. The tension itself is not new, however: in America half a century ago it was known as the ‘milk bottle versus Grimm’ controversy. Although there is a clear distinction between extreme examples of fantasy and realism, the intervening grey area encompasses a great deal of fiction which successfully mingles the two. Thus Sparring with Shadows, though on the face of it another example of contemporary realism, is peopled with characters who are clearly shaped to serve the author’s intentions; they’re believable but they’re not as ‘real’ as hyper-realists might prefer. Black Ice, on the other hand, is built on elements of the fantastic – spirits, poltergeists, séances, and the like – but it sets those elements against a recognisable late twentieth-century background in which a teenage girl is struggling to understand the disintegration of her parents’ marriage.

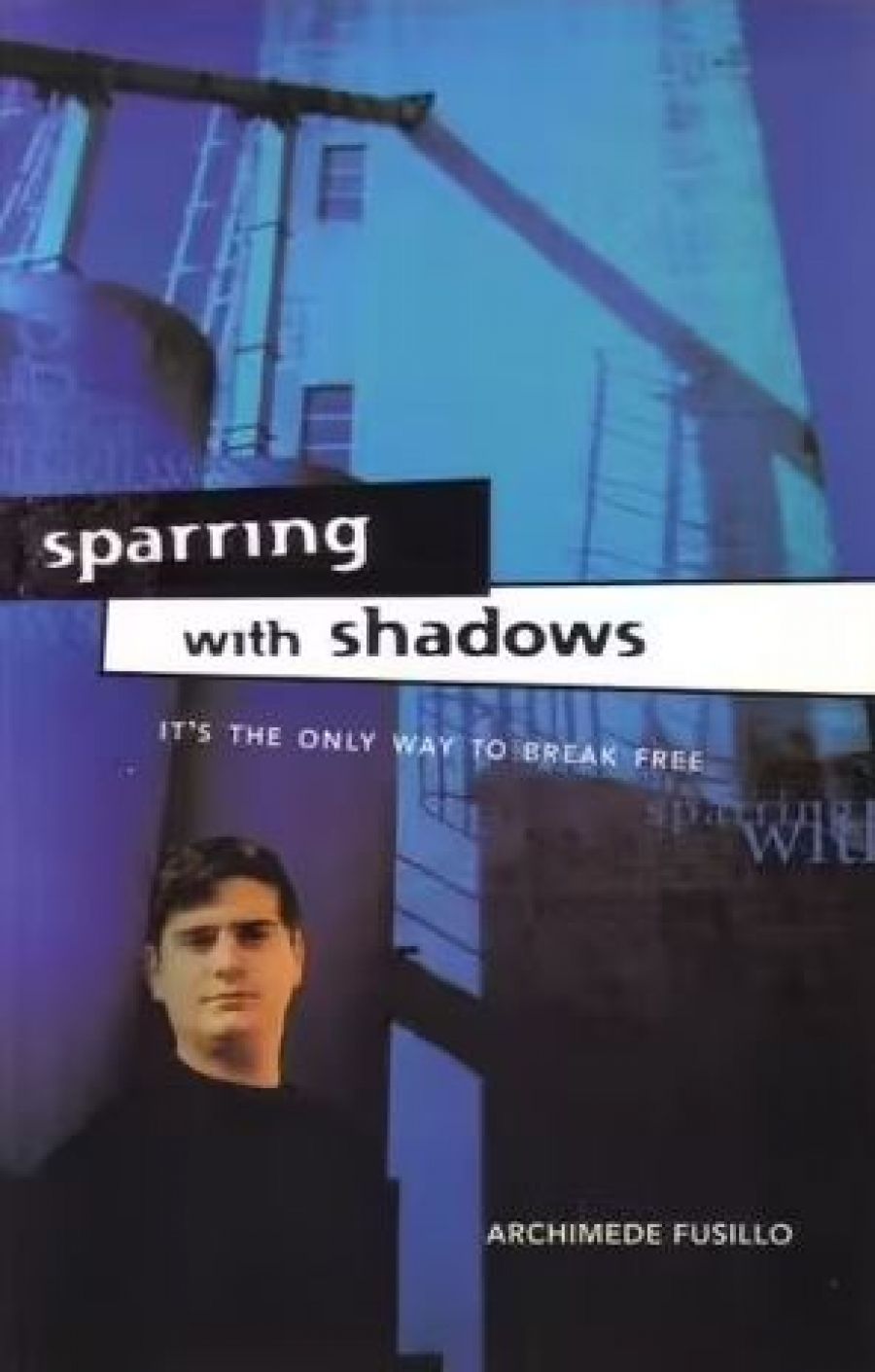

- Book 1 Title: Sparring with Shadows

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin $12.95 pb, 219 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: www.booktopia.com.au/sparring-with-shadows-archimede-fusillo/ebook/9781742284507.html

Sceptics could be forgiven for thinking that Archimede Fusillo’s novel was conceived as a masculine counterpart to Melina Marchetta’s bestselling Looking for Alibrandi. Its male first-generation Italian-Australian narrator, fifteen-year-old David, tells us how he starts to feel the need to break out of the tight expectations of his parents – expectations whose oppressiveness, he discovers, he has, to some extent, created for himself. A ‘go-nowhere, pudgy, intellectual Italian guy’, David is uncomfortable with the ribbing he gets at school from thuggish fellow students who are more excited by sport than thought. One such student, Nathan, comes from a far more troubled, though in many ways less intrusive, family than David’s more or less traditional Italian one. Nathan befriends David – for which David is grateful, if a little suspicious – and introduces him to a mentally retarded boy called Ralph, whose relationship with Nathan is revealed after a tragedy to be much closer than David has at first been led to believe.

Though it clearly enough evokes Melbourne suburban life, Fusillo’s prose never quite soars. Moreover, many of David and Nathan’s conversations are improbably clear-headed and insightful for fifteen-year-old boys. However, Sparring with Shadows does offer rewards. It’s studded with the kind of masculine truths that have tended to be ignored of late in the relatively feminised young adult fiction scene. David believably acquires some understanding that it is the shadows of his own ignorance that have led him to give to others the power that they wield over him; and Fusillo is skilful in suggesting that when children from dysfunctional families attack the values of happier families it is often a means of concealing their envy. In the end, while not closing its eyes to the problems of the real world, Sparring with Shadows pays a (somewhat wishful) tribute to functional families, with all their natural stresses and confusions.

Black Ice by Lucy Sussex

Black Ice by Lucy Sussex

Hodder, $14.95 pb, 186 pp

It’s much harder to find the nuggets of gold in Black Ice, the story of Syb, a fourteen-year-old girl who is ‘in the middle of a Goth phase’. Her parents, whom she is accustomed to call Martha and Davo ‘like almost everyone else did’, become estranged shortly after the family moves into an austere new house which is notable for its unceasing coldness. Eventually we learn from Hille, the mysterious new-ageish housekeeper whom Syb’s father employs, that the house is full of black ice – bad vibes. Initially the culprit is thought to be the spirit of a baby which has ‘chosen’ not to be born to Syb’s mother in such unsettled and inhospitable circumstances. The ‘bad vibes remain, however, even after Hille has exorcised the spirit.

Lurching erratically thereafter into improbable melodrama complete with climactic car chase and gun-point confrontation, the novel manages to embrace themes as divergent as memories of Aboriginal massacres and the problem of pornography on the Internet. Unless I missed a vital piece of information – which, I claim in my defence, would not be difficult given the helter-skelter pace and opportunistic plotting – the first part of the book seemed only tenuously connected with the rest of it. Incident is piled on haphazard incident and new characters are brought in on a seemingly ad hoc basis. At times, the book doesn’t appear to be taking itself seriously – indeed, there’s a hint of satire, though whether that’s intentional or not I can’t be certain. The result is a feverish, if never quite incoherent, mishmash of ideas and possibilities, none of them fully realised. To make matters worse, the editing and proof-reading is as bad as I’ve ever seen. The inability to distinguish between ‘alternative’ and ‘alternate’ is perhaps too common nowadays to take exception to, but it’s surely still reasonable to object when Syb wonders of Hille ‘Had she played on Davo and I?’ It’s also not good enough to find ‘whiskey’ on one page but ‘whisky’ on the next; similarly, ‘tyre iron’ followed by ‘tire iron’. Even the name of the ice-bound house, ‘Hillcrest’, is once given as ‘Hilltop’. I certainly have no problem in principle with the mixing of fantasy and realism. How could I, when I firmly believe that’s what all fiction is about? But even (indeed, especially) when there’s a large ratio of fantasy to realism, the creation of an illusion of believability is crucially important. Black Ice simply isn’t believable enough.

Comments powered by CComment