- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Selected Writing

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

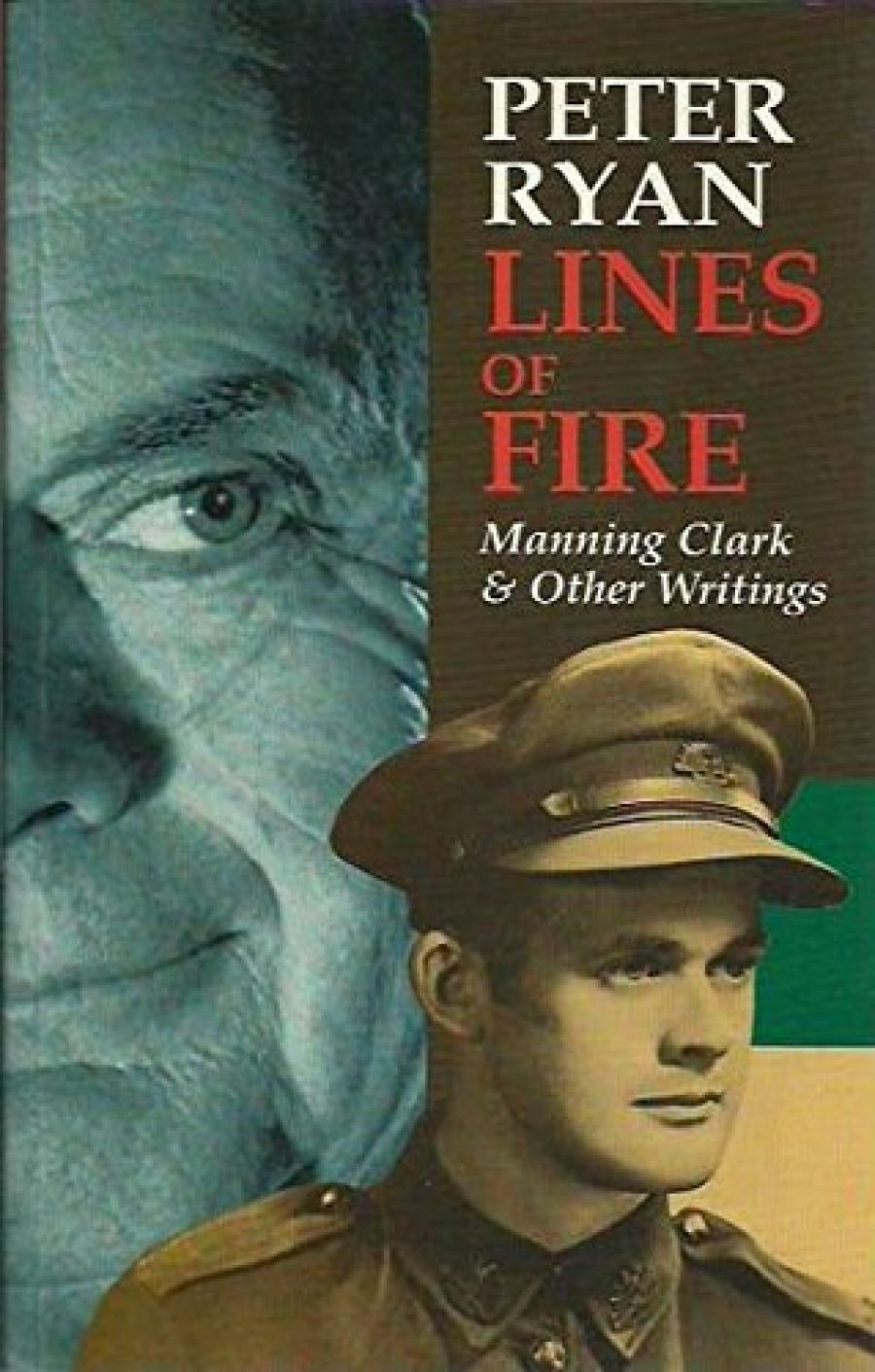

This collection of Peter Ryan’s writings, Lines of Fire, is no grab-bag of oddments. The pieces included here are given an impressive unity by the author’s imposition of his presence, by his trenchancy, elegance of expression, a desire to honour the men and women of his younger days and to excoriate a present Australia in which too many people wallow in ‘an unwholesome masochistic guilt’. The finely designed cover shows a wry, ageing, wrinkled Ryan smiling benignly over his own shoulder, or rather that of his younger self, in uniform, in late teenage, during the Second World War. What happened in between is richly revealed in the elements of Lines of Fire.

- Book 1 Title: Lines of Fire

- Book 1 Subtitle: Manning Clark and Other Writings

- Book 1 Biblio: Clarion Editions, $19.95 pb, 256 pp

The book begins with an excerpt from Ryan’s rightly celebrated memoir of his war work, Fear Drive My Feet. Ryan was involved in conducting reconnaissance of the Japanese, often on his own, for more than a year, in the Markham River country outside Lae. This was the service for which he was awarded a Military Medal. The episode included is the account of betrayal and ambush in which his friend was killed and Ryan – literally over his ears in mud – miraculously (but not, he insists, providentially) managed to escape.

Next comes ‘Reviews and Reflections’, a selection of Ryan’s journalism from 1972–96. A.K. Macdougall, in his introduction to the book, gives Ryan a backhanded compliment when he says that ‘publishers are not renowned for their ability to write at all’. For a quarter of a century, from 1962 to 1986, Ryan was the boss of the Melbourne University Press, during what may well have been its golden age. Of the tarnish – the Manning Clark controversy – he has had plenty to say and it is reprinted. But before then, we are treated to a miscellaneous savouring of good things of the world, however unfashionable some of them may be. Thus, recording his pleasure in the poetry of A.E. Housman, Ryan reckons that ‘nowadays to admit such a thing is rather like owning up to a passion for sweet sherry’.

He writes of his short-sightedness and of the complexities of what we call ‘vision’, of the flabbiness and fatuity (as he judges) of much state-sponsored contemporary writing in Australia: ‘that old harlot-midwife the Literature Board is summoned on the pretext that all this grunting has something to do with birth’. Unapologetically Ryan bemoans ‘Australia’s present pathetic lack of national self-confidence’, contending that between the 1920s and the 1980s, we ‘became, as individuals, less able to help either ourselves or others’. Some of this, he believes, has to do with the effects of ‘the evil sequestration of Canberra’ on those who work there.

The third part of the book, ‘Men of Character’, contains affecting tributes to the jurist Owen Dixon, to Alec Hope, and to Paul Hasluck, ‘the Private Man’, among others. These reckonings work incidentally as an ironic prelude to the next section of Lines of Fire, which collects his demolition of Manning Clark’s reputation and two consequent replies to the critics, most of them professional historians, of the initial sally. Ryan says, justly, that – in respect of his accounting of ‘Clark’s errors, distortions and bad writing’ – ‘on not one single point was any refutation attempted’.

What he did suffered by following the completion of Clark’s History (most of which Ryan published) and Clark’s death. As Ryan conceded, this was ‘a painful labour, performed without relish, and one certain to cost me friendships’. Since then, Clark has been subjected to vicious attacks and innuendoes out of all proportion to any supposed offence. Ryan has had no part in them. The cogency and particularity of his attack has gone without a single weighty rebuttal. Perhaps this has been in the hope, probably deluded, that it will be seen as issuing from personal animus, and will therefore be forgotten.

Lines of Fires concludes with ‘Country Matters’, among these being the delight Ryan takes in his property at Rainy Creek, the redolence of old-time country stores, and city-bred misapprehensions of the bush: ‘Kangaroos induce the most mawkish madness of all’. If one did not know that Peter Singer was a professor, Ryan writes, ‘one might almost suspect him of being a ratbag’. Life in the country is, for Ryan, a time for refreshment. As a permanent condition, ‘unbroken and undiluted, [it] would make me surly, and then suicidal’.

So he still comes to town: to Melbourne where his fruitful businesses have long been conducted; and he still goes to Papua New Guinea, a country for which his love is untempered, however much he despairs at what local and Australian politicians have done to it. Lines of Fire, very finely produced by Clarion Editions, does justice to the humane breadth of Peter Ryan’s mind and heart, to the integrity of his prose, to the sense of responsibility that he brings to each cause with which he engages. Happily, he continues to write ‘As I Please’.

Comments powered by CComment