- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Christine Wallace’s book, in twelve chapters, is actually two books. Chapters 1-7 deal with Greer’s childhood and family, secondary and university education including MA and PhD theses, her sexual history and engagement with the counterculture in Britain which pivots around writing for Oz, her career as a groupie and membership of the Suck editorial team. Events are arranged chronologically but it’s often hard to work out the date (and thus Greer’s age), whether she’s in Melbourne or Sydney and, since the chapters are of very different lengths, how much has been included or omitted.

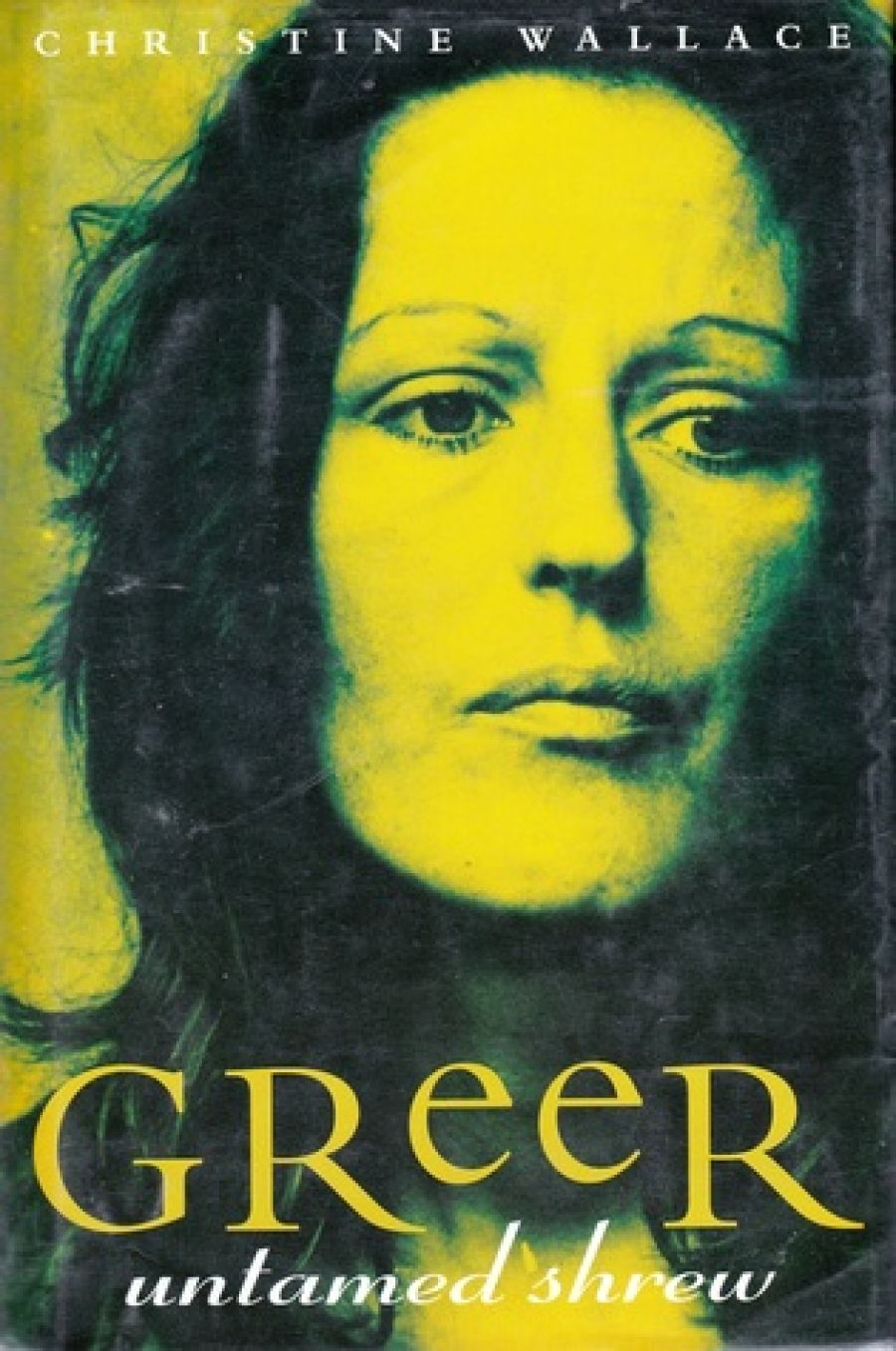

- Book 1 Title: Greer, Untamed Shrew

- Book 1 Biblio: Macmillan, $35 hb, 386 pp

If an unauthorised biography can offer the warts-and-all story, then the bio-part of this book (chapters 1-7) is awfully warty. ‘It all began with Peggy and Reg’ on page one but by page four the newly-born Germaine is disputing the derivation of her name with her mother. The future Dr Greer was slow to wean and by page seven ‘Germaine was resentful.’ I wonder who said this? On page twenty-one Wallace allows that ‘Greer transcended her physical awkwardness’ by playing a ‘brilliant Duke of Plaza-Toro’ – a man in other words – in The Gondoliers. There’s something about the tone here. ‘Germaine’s low self-esteem did not preclude intellectual arrogance,’ announces Wallace with absolute confidence. ‘The summer at the end of Greer’s second year at university was as muddled and melancholy as the year before.’ No problem about the facts there. Next sentence, ‘Late in the academic year Greer had her first abortion.’ One sentence later, ‘Soon afterwards Greer met the first man with whom she could enjoy reciprocal love’. Is this what’s called a ripping pace? Three pages later, ‘Just after moving to Carlton, Greer was raped’. I realise there’s a lot of life to get through here, but the relentless laying down of fact A (ugly flesh) beside fact B (abused flesh) produces, if not a prurient account then at least, a flat, distanced, third-person narrative in which there’s no space for analysis or judgement or sympathy.

There’s a line that tracks alongside Greer’s body here. Just after the low self-esteem, Wallace identifies ‘a nascent feminism’ in Greer’s reaction to her brother’s favoured treatment. When Greer ‘cracks hardy’ about the rape, some twenty-five years later, Wallace comments that Greer’s language ‘suggests a striking lack of feminist consciousness.’ Later, neither of Greer’s research theses showed any signs of feminist critique – nascent or otherwise (chapters 5-6). The Drift (in Melbourne) and The Push (in, Sydney) combined giving Greer’s sexual liberation (read promiscuity) a philosophical (Andersonian) format which licensed Greer to live out a heterosexual rough trade fantasy (read du Feu and others) while writing off the entire women’s movement. ‘The woman the press would dub the "high priestess" of women’s liberation was about to deliver a sermon, not from the Mount, but from the Mound of Venus’ – otherwise known as The Female Eunuch.

Although Greer, by her own admission, failed every litmus test for feminists ever devised, The Female Eunuch changed women’s lives for the better if not by liberating them then by giving them a language in which to articulate their sense of oppression and dissatisfaction. Wallace concedes this point but it’s a problem for someone whose knowledge of feminism is just too thin to go policing the boundaries. Wallace is, too, an unfortunately hap listener.: she just can’t hear what Steinem and Johnston for instance are saying about the history of feminism, the necessities of those early days in the media or Greer’s courage in just being out there.

The book that made her name is Greer’s real crime and once that book enters the narrative Wallace’s biography loses the plot. As the chronology weakens in chapters 8-12, the narrative doubles-back to dizzying effect and all the while Wallace is laying down fact A (a new book by Greer) alongside fact B (Greer’s infertility). This book has been superbly edited but not even the skills that produce the seamless narrative of chapters 1-7 can rescue the latter chapters where dates evaporate, connections between paragraphs are vague or the logic of individual chapters (especially ‘Paterfamilias’) is elusive.

The stereotype remains: arrogant, loud-mouthed and sexy; the egotistical media junkie who changed the way women thought; the powerful polemicist cruelly mining herself for her writing; the radical mind Cambridge failed utterly to engage. The wonder is not that Greer became a Tory; only that it took so long. But so do the questions: what makes a brilliant and successful woman intellectually self-destructive? Why does a woman who, in Jane Gallop’s phrase, thinks through her body, hate that body? How did Greer, always afraid of women, find the courage to be any kind of feminist? Why does a woman afraid of her mother, remain a daughter? Peggy Greer’s ‘when I hear her speak, I can’t distinguish her voice from mine’ sent shivers down my spine.

This book demonstrates Greer’s capacity to antagonise and outrage without, apparently, approaching her use-by date. But I’m grateful to Wallace for Liz Fels’ wonderful interviews with Greer in 1979 and 1984 for the ABC’s Coming Out Show. Fels suggested Greer had been scapegoated for ‘standing out the front and writing The Female Eunuch.’ ‘Oh yes, but I’m not whining about that. I always expected the feminists would attack me first, and it’s the hardest attack to bear ...! think I’ve usually deserved the criticism I get, by the way ...’ You can’t argue with that – so Greer gets the last word, again.

Comments powered by CComment