- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: After the Heat

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The funny ways we have of writing about sex and how rarely it really works. The memory of how it feels, what is involved, what it means. How strenuously we, as writers and as people who have done it and then talk or write about it, try to capture the movement and intensities we remember. And how ludicrously it so often comes out at that second division, once removed from the flesh and heat.

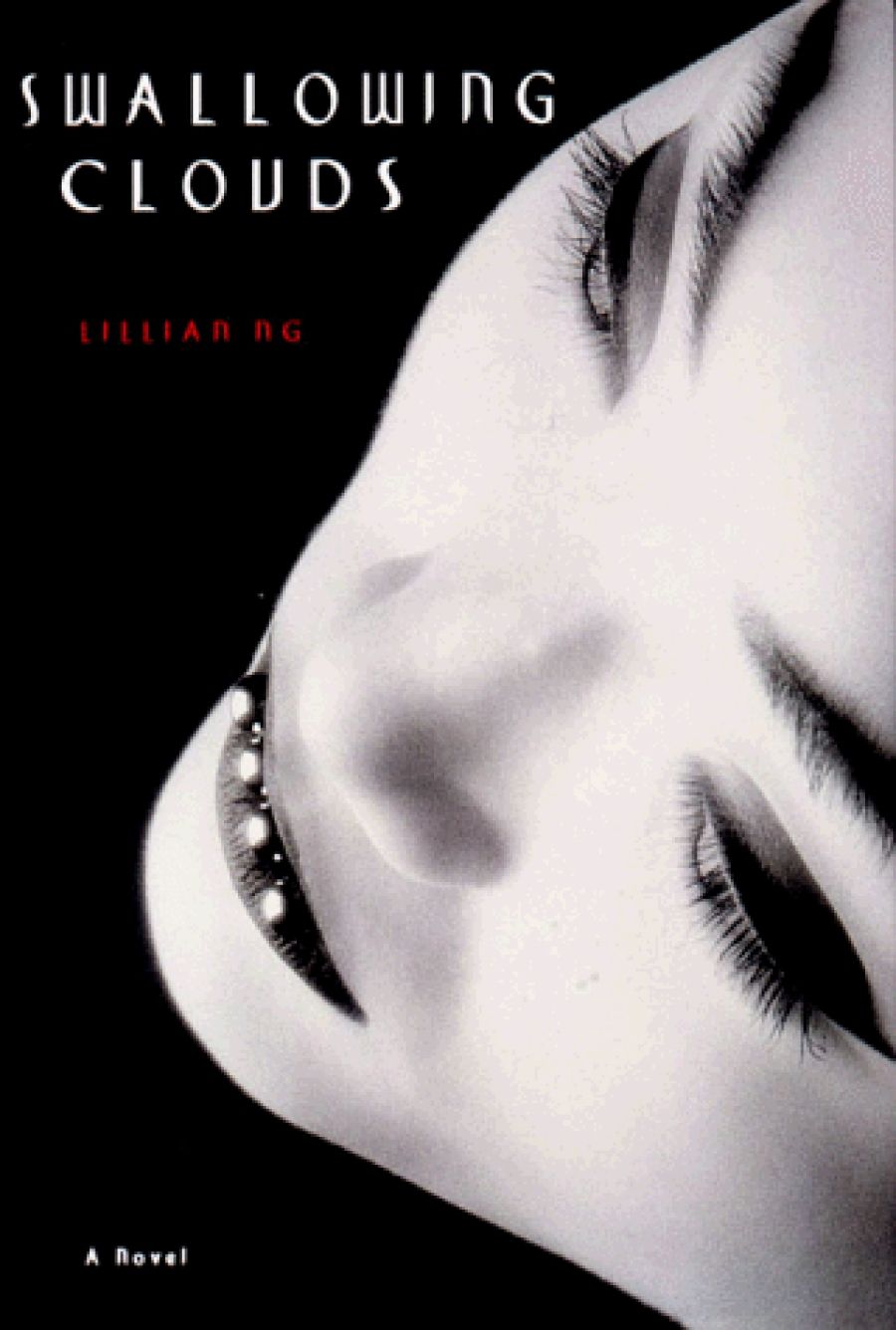

- Book 1 Title: Swallowing Clouds

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin, $19.95pb, 305pp

Lillian Ng’s second novel, Swallowing Clouds, slips into traps of trying to make an erotic dramatic scene and, largely, falls short of the task. The naming of body parts and rituals, the material of sex and all the sensual stuff, is, I think, its first problem; there is a comic joy to some of the catalogue of names used, but when they appear again and again that charm is likely to wear down or even off. The jade whisk; the amethyst agaric peak; the jade fountain; the coral twin peaks; the red pine peak; Chinese sausage; the passage of yin; her grotto. As in:

His red pine peak rose precipitously, a lone summit above a swift river. Excited by his yang essences, her grotto was inundated with fluid. It dripped and bubbled, and the secluded spring tumbled out of the mouth of the river of yin.

And:

Zhu Zhiyee inserted his jade whisk into the grotto, to act as a drinking straw, in order to siphon the secretion to extract and nourish his yang ... Finally he crouched down, like a tortoise, to drink at the jade fountain.

Doesn’t sound too sexy, does it? (Wait till you read about breasts and nipples and a butcher’s sharp eye.) I tried to work out throughout this novel, described as an erotic tale, what is going on in it, and what is going wrong. The conceit of using ancient Chinese texts as references for talking about the horizontal folk-dancing caper (to use an Australian irreverence) is interesting and potentially a way to get around the cringe factor of an over-determined subject like sex. But matched with the melodrama of the writing, the implausibility that is the result of the novel trying to be too many different and incompatible things, and the repetition of these namings of the implements of pleasure, it sinks, I’m afraid, into banality.

A confusion, throughout, about the tone: whether irony is at play, or whether I should keep reading these names as euphemisms, whether it is a masking device borrowing from other texts, a new way to obfuscate. Whether, in fact, I was being too precious; the preponderance blunted my sympathy, my openness, though.

As does the contemporary counter-story of the return of Syn to China with Australian tourists in 1994. But I’m jumping the gun, because what I wanted to say in the first place was that the novel starts wonderfully well. The prologue sets up a scene of Chinese tradition and sexist practices: a woman is drowned in a wicker pig’s basket in Shanghai in the manner of a festive event in 1918 for the crime of adultery. She is the last recorded case of such a punishment; her lover is let off after a police bribe. Her demise is recounted vividly in this opening humdinger, and it reminded me of one of my favourite ever books, Maxine Hong Kingston’s Woman Warrior, published in 1977. The pain and retribution that is meted out unevenly; the dangers of sexual desires.

Our protagonist Syn is the reincarnation of this poor woman – she is told this by a blind soothsayer just before she hops on a plane for Australia, where she will study English. Her expenses have been paid by a village eunuch. As the novel progresses, we find out more about her early life in China, about the repercussions of the Cultural Revolution, her parents’ disaster, and something of her own monstrous initiation into sex through ritual rape and abuse. The novel’s timeframe is before the Tiananmen Square massacre to 1994. Syn is one of the many Chinese students stranded in Australia.

Her lover is a butcher and her employer; his means and personal power has something of a shifting quality. Sometimes, he is required to do his butchery in his shop all day, while at other times he is a wheeler and dealer, albeit one who is dominated by his neurotic and greedy wife, and rich. This development of character and event is not fully realised, but the erotics are more important in the scheme of the book’s progress. Because I think I have worked out why it’s all there anyway: it’s to prove the soothsayer’s prophecy that the best action in this re-run of life is to ditch the man and keep the money. The man will always be unworthy, unreliable.

You are that ghost back on earth. To have your revenge. On men. Not to kill or maim, but to take their money. To get even. You’ll never be successful as somebody’s wife.

Not only are you drowned in a pig’s basket in public, but you must pay for past crimes into the next life. Take revenge: take his money. And that has been the purpose of the novel, to show this in action. I wanted more.

The present is represented with this trip back to China by Syn to take her mother back to a new life in Australia. It could have been comical if it hadn’t been so earnestly written to tell us about China’s culture and history: it is a guided tour of the worst order, ‘an exquisite packaged tour. A boutique tour organised by a cultural group: the ACT (Asian Cultural Tour), led by an eminent Professor in Oriental Studies of the University of ACT’ made up of thirty or so Aussies who ask dumb questions so that we, fellow reader, can be enlightened.

Comments powered by CComment