- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Essay Collection

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: World Children

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

What do the fab four of this book have in common? Not simply that they are Australian and expatriate, that they are writers who have achieved a degree of celebrity and performers who have made skilful use of television.

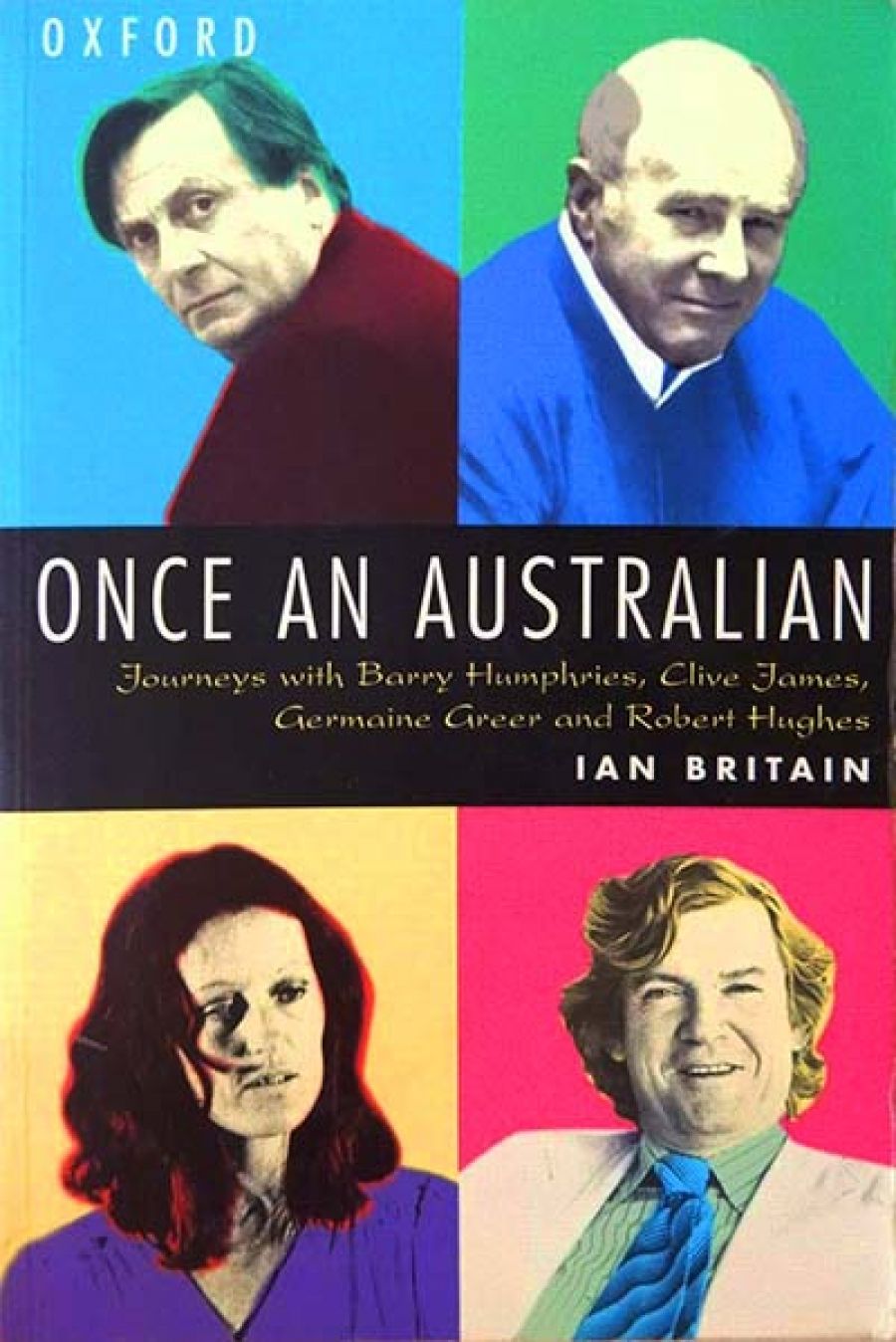

- Book 1 Title: Once an Australian

- Book 1 Subtitle: Journeys with Barry Humphries, Clive James, Germaine Greer and Robert Hughes

- Book 1 Biblio: OUP, $39.95hb, 290pp

Ian Britain has an intriguing list of what else they share. ‘Anaglyptic, hispid, kludge, tede, kurtosis, anophobia, emulgent, rachitic,’ he suggests, singling out some of the more arcane words they have scattered through their writing. (I’ve selected two from each author.) ‘This is hardly a representative sample of their general diction or modes of speech,’ Britain says, ‘but it can supply some clue to the intersecting patterns of their lives. It is a symptom –perhaps the most telling one – of whatever distinctiveness or unity they can be said to have as a group.’ These four are ‘Word Children’, Britain says: the fondness for the arcane might be their way, he suggests, of announcing their arrival from the province to the metropolis, and, once there, of consolidating it.

Once An Australian consists of four biographical essays framed by a general introductory chapter and an afterword. The subtitle of the book, Journeys with..., implies a certain amount of intimacy with his quartet, but the trip Ian Britain takes is strictly an intellectual one. He has not interviewed any of his subjects: he takes his raw material from their writing, and from the public record. There is plenty to draw on.

These are not retiring people: they have all written copiously, and with varying degrees of evasiveness, about themselves. Greer is the most self-revealing, Hughes the least. This material allows Britain some scope for reflection on the impact of absent fathers and indulgent mothers. And they all have a considerable body of work, strong opinions on a variety of subjects, and few inhibitions about pronouncing on them.

Britain subjects them to careful, measured scrutiny. These essays are elegant assessments with many acute moments. He places Humphries’ body of work in a theatrical and literary tradition that takes in Chaucer, vaudeville, the seventeenth-century masque, and Beckett. Humphries was cast in a 1957 production of Waiting for Godot, and Britain uses this fact imaginatively in the conclusion to his chapter, thinking about the way Humphries invariably uses Australian material, and revisits moments from childhood experience.

He writes:

‘The essential doesn’t change’, reflects Vladimir, Estragon’s fellow-tramp in Waiting for Godot. The slave-driver, Pozzo, complains to Estragon a little later: ‘I don’t seem to be able to depart.’ ‘Such is life,’ replies Estragon. And such is the life of the Melbourne actor who portrayed him in 1957: a compulsive itinerant rooted to one spot. It remains the strangest thing about him.

On Clive James, Britain is surprisingly restrained. His James is a Humpty Dumpty made up of pieces that don’t fit together. He writes about James’ early loss of his father, who died in 1945, killed in an air crash after being released from a prisoner-of-war camp: the fatherless only child felt a sense of dislocation, Britain suggests, which became a motif for the rest of his life. And there is some intriguing speculation about the place in James’s life of ‘a form of longing which is not only incapable of fulfilment but which no amount of achievement in later life is able to assuage’, a longing for beauty, male and female.

Comments powered by CComment