- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Children's and Young Adult Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Coming Out of Hiding

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Gleeson is an award-winning novelist for young readers, winning the 1991 Australian Children’s Literature Peace Prize for Dodger and the 1997 Children’s Book Council Book of the Year for Younger Readers with Hannah Plus One. Her other novels include I am Susannah and Skating on Sand, and her picture books include The Princess and the Perfect Dish and Where’s Mum. She is an accomplished writer, which is reflected in her latest novel for older readers, Refuge.

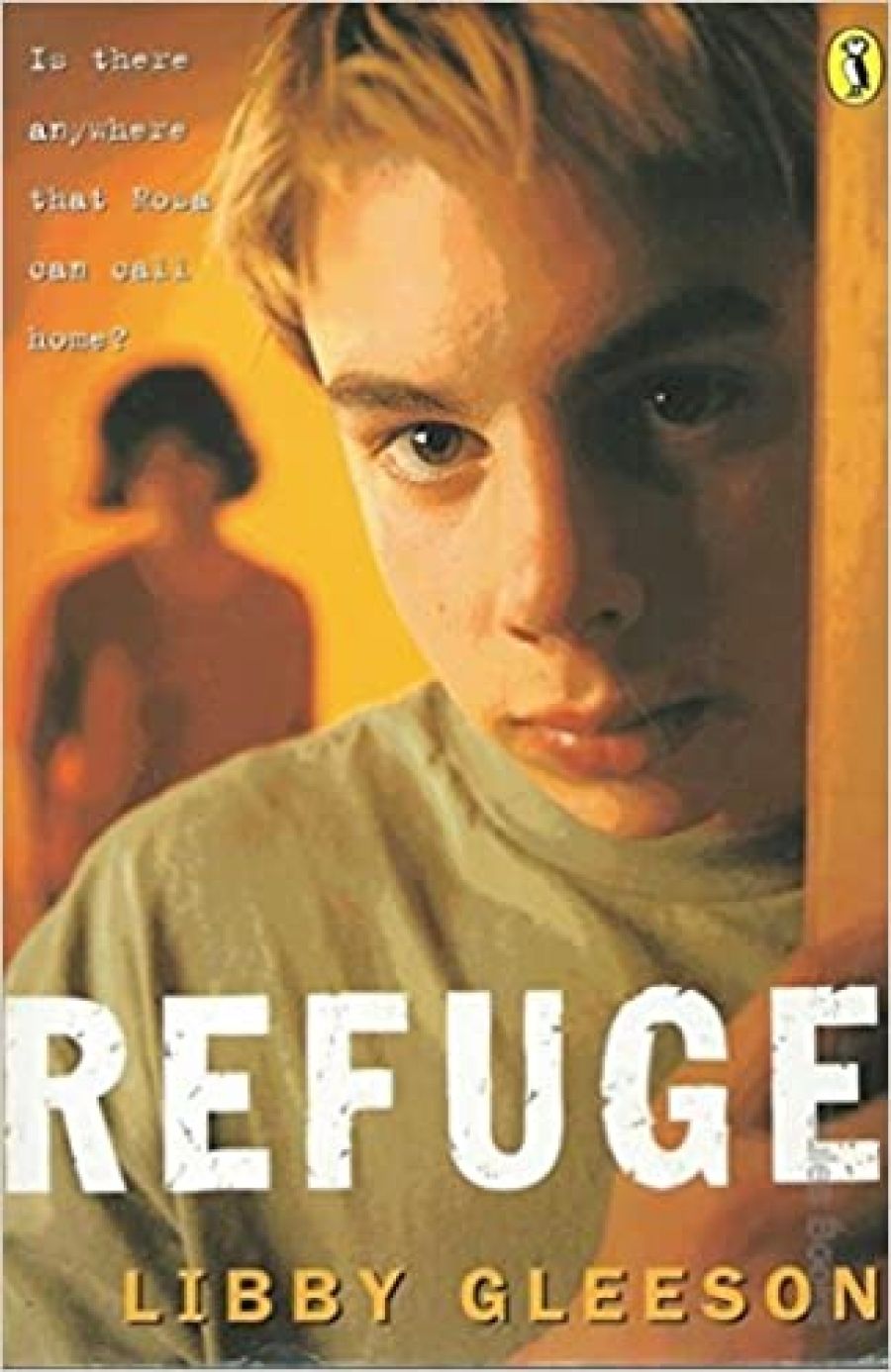

- Book 1 Title: Refuge

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $12.95, 150 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/5bDgKj

Refuge’s plot is a contemporary one. Andrew is a teenager who missed the Space Girl’s tour; he spent his summer up north on a museum dig where amongst like minds he is treated as an adult. But it’s the end of the holidays. He returns home to his parents’ large house and to an awkward silence that stems from an ongoing fight between his mother and his older uni-student sister, Anna.

Andrew’s confusion is believable and so too is his love of archaeology and his interest, and relationship with, the museum. It is to the museum and also to his memories of the dig that he returns in order to sort out the moral problems his sister presents to him.

Gleeson writes powerfully and sensitively here.

He doesn’t want to look at virtual rocks on computer screens, at latex moulds or rocks in glass cases. He wants to touch and handle them. He wants to rub their surfaces with the soft pads of his fingers till the dust comes off and works its way into every crack in his skin, every line on his hand, heart line, life line.

As the novel progresses we are gradually shown more sides to the tantrum-driven older sister. Her battle with her mother is ideologically driven and one close to home. Her mother was a student activist in the heady days of the Vietnam War and Anna has grown up with stories of that student struggle. But now it is her turn to change the world, to question and upset the established order. Here she runs into two problems. Firstly she doesn’t have a cause as monumental as the Vietnam War and so her mother doesn’t take her daughter’s political struggles seriously. Secondly, over the years her parents have become less and less radical, (haven’t we all), and as a consequence less and less likely to break the law, even under the guise of civil disobedience.

When Anna eventually finds a cause large enough to equal anything her mother ever did, it is her mother who becomes the obstacle, the conservative force she needs to challenge. And Anna’s cause is a powerful and contemporary one – hiding East Timorese refugees from the authorities who want to deport them to Portugal. Australia’s blind eye to the plights of the people of East Timor is worrisome and will no doubt be judged by history as one of our darker or ill-informed foreign policies. This national refusal to embrace our regional responsibility is reflected in the way Anna’s mother refuses to engage with the problems of the refugees and, in particular, the difficulties and helplessness of Rosa, a refugee and student Anna has befriended.

In presenting these political and moral issues Gleeson does not simplify the questions. Her characters are well developed and struggle with their side of the debate. We are, for example, allowed to sympathise with the mother. Andrew describes his mother’s playing of the saxophone:

He cannot find words for the feeling in the music. It is as if their mother is playing some pain or sorrow so deeply held that words do not exist. Only her music coaxed from the instruments with all her body and breath can create such lamentation.

Gleeson has given us a strong work but I cannot leave this review without mentioning a problem I had with the text. We enter the narrative strongly and convincingly through the eyes of teenager Andrew, but that focus is significantly softened as we learn more of Anna and her political involvement. It is as if Gleeson wants the reader to enter the narrative from two doors, Andrew’s and Anna’s, or to put it another way, as if Andrew’s story exists only to frame Anna’s. I found this device awkward and distracting. I had enjoyed Andrew’s calmness, his curiosity and his silent scrutiny of his world, and was sorry to leave him behind for the more volatile Anna.

But this criticism is not to mar the Gleeson novel in any significant way. She has written an interesting and timely novel and as a baby boomer I, not always comfortably, identified with its ageing once-hippy-lefty parents struggling with the compromises that age and affluence generate. It is no doubt good for my soul to have those still waters muddied occasionally. And it is no doubt good for the national soul to question our nation’s attitude and lack of concern for the people of East Timor. For this I thank Gleeson.

Comments powered by CComment