- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Constitutionally unconventional

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Still fondly remembered as one of the Doug Anthony Allstars, although most recently known for biding his time in the depths of Channel Nine between those twin peaks of high culture, Don’t Forget Your Toothbrush and Little Aussie Battlers, Tim Ferguson has obviously not been idle, instead indulging in everyone’s favourite pastime – Canberra-watching. Inspired (or possibly horrified, if Left, Right and Centre is anything to go by) by what he has seen, Ferguson has created a monster – Luther Langbene.

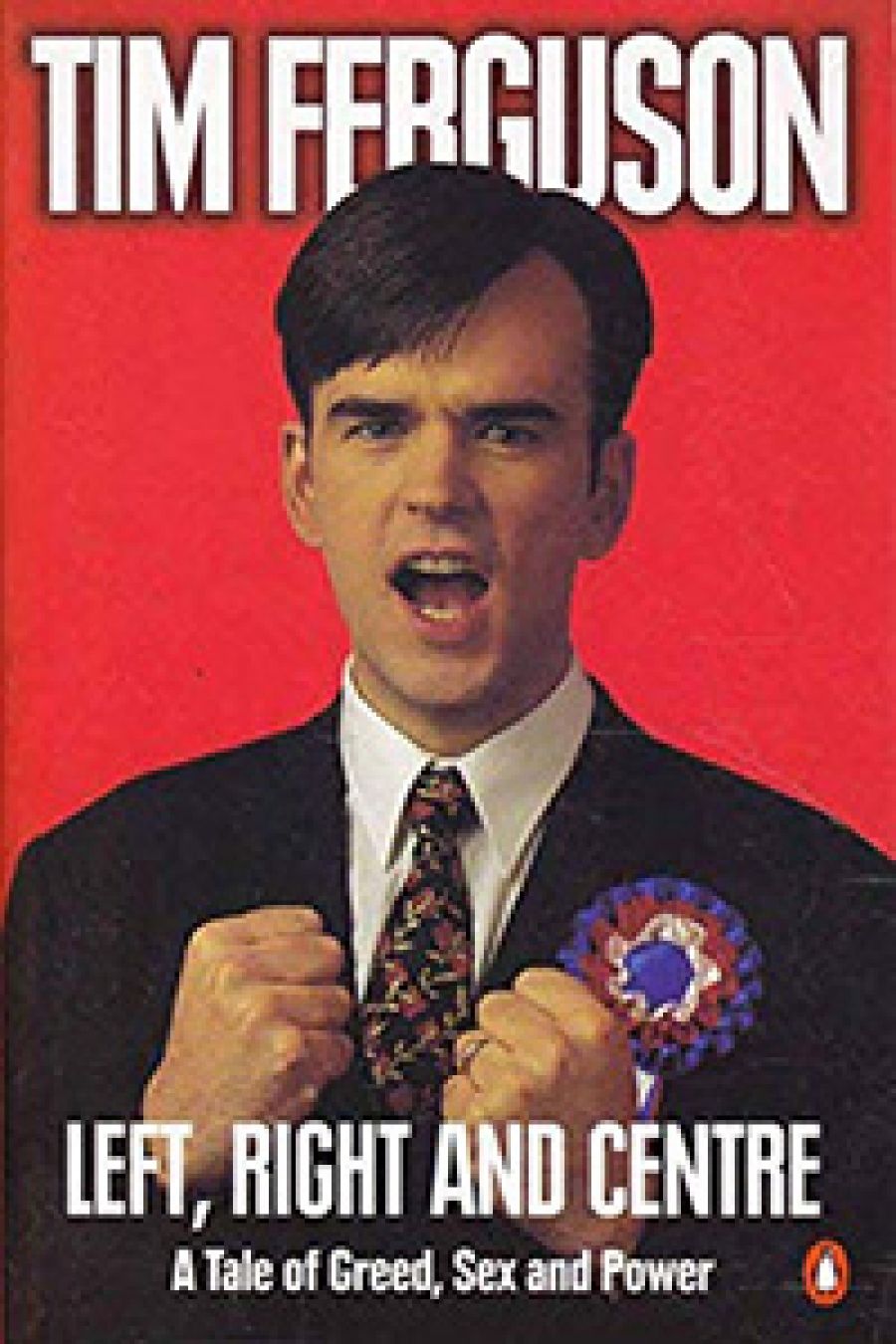

- Book 1 Title: Left, Right and Centre

- Book 1 Subtitle: A tale of sex, greed and power

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin, $16.95 pb, 256 pp

Langbene, the son of a West Australian mining magnate, has only one modest aim in life: to overthrow the government of the day and to establish himself as self-appointed dictator of the not-so-distant, fictitious Republic of Australia in which Left, Right and Centre is set – all in the nicest and most democratic way possible, of course. His tools? A winning smile, a likeably roughish personality and every underhand, two-faced, manipulative trick known to the modern politician.

In a series of painfully transparent attempts to win over just about every interest group around, Langbene claws his way into Parliament by tailoring his views to whichever group he happens to be addressing: to the proudly rural men of the Port Hedland Cattle Sale, he offers ‘For too long this government has been squeezing the little man. Well, little men might like being squeezed in big cities like Sydney, but we don’t,’ while the militantly arms-bearing Federation of Farmers Gun Club is treated to

‘Now, just because a digger returns ... with a screw loose and does his family in, that’s no excuse for making the rest of us suffer. Besides, psychos can kill with breadknives just as easily. Are our families going to be reduced to slicing bread with a fork?’

At one point on a radio interview, he jumps yet another fence to side with single mothers – ‘the ignorance about the difficulties of single motherhood shown by the feminist movement is criminal.’

His stated aim is, of course, like all politicians – the common good of the country; while gazing over an idyllic Australian vista he predicts: ‘the only trouble is, without a bit of care, without a bit of protection, all this ... all this will vanish in a puff of wind.’ But how to prevent this? ‘Strength, independence, justice. That’s my shopping list.’

However, once elected, Langbene’s less than politically correct views come to the fore: ‘If you choose to have a child, you must accept that many other choices are no longer available to you. If you disagree with that, you should have your children confiscated by the government.’ In his maiden speech to the Parliament, he suggests that, to combat the country’s economic and social malaise, ‘two-hundred-per-cent tariffs, a waterfront run by the military, new taxes on foreign investment and a wage freeze for ten years should have us coming up roses.’

Once firmly ensconced in Parliament, his strategy is to do absolutely nothing – ‘If running a business has taught me anything, it is that power is a last resort, to be used when pressure fails. The less you exercise it, the more potent it becomes.’ This is not seen as a threat to his popularity with the electorate, though – ‘The punters love politicians who don’t make waves. “Where’s the harm?” they say. “He’s such a quiet man.”’ Indeed, after having wooed them during the election campaign, Langbene develops quite an unhealthy regard for the general public – ‘Every time the Silent Majority get a chance to open their mouths, we are treated to a feast of xenophobia and cultural cringe. That’s why we keep them silent.’

Eventually Langbene cannot resist revealing his ultimate aim – Australian supremacy through an implied military threat: ‘I don’t want an arsenal of things. One bomb, one test and we don’t need any more. Everyone will assume we have more.’ Again, in yet another light on the average Australian’s political apathy, no electoral backlash is anticipated as a result of this extreme action: ‘the Australian people just want to go back to sleep again. They’ll let us draft the dole bludgers, they’ll let us detonate our bomb, they’ll let us run the joint so long as they can ignore us and go on having their barbecues and beach holidays.’ Having manufactured a crisis where this course of action seems to be the only answer, Langbene asserts: ‘We may not like it, but Democracy comes from the barrel of a gun.’

Perhaps the most unnerving part of Left, Right and Centre is that, despite the fact that Langbene, with his total disdain for the community and the democratic process, is a totally despicable figure, he would probably do quite well on the contemporary Australian political scene. After all, what he represents is not that far removed from what we have come to expect in our daily diet of sound bites and news grabs from Canberra. Indeed, in a society where someone like Pauline Hanson can get elected to the Federal Parliament or where barely half of the population cares enough about the future of the country to vote for the make-up of the constitutional convention, is there really anything that surprising in a carefully engineered massive economic and social crisis, complete with rioting in the streets, being solved by just one teensy, weensy little nuclear bomb? I’d vote for it!

Comments powered by CComment