- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Phillip Knightley prefaces his book with these definitions, so which does he want to identify himself with? Surely not the first. A mere scribbler he may have been early in his career, especially when he was recycling other journalists’ stories (hacking them about, perhaps?) at the London officer of the Australian Daily Mirror. But no-one, now, could call him a poor writer.

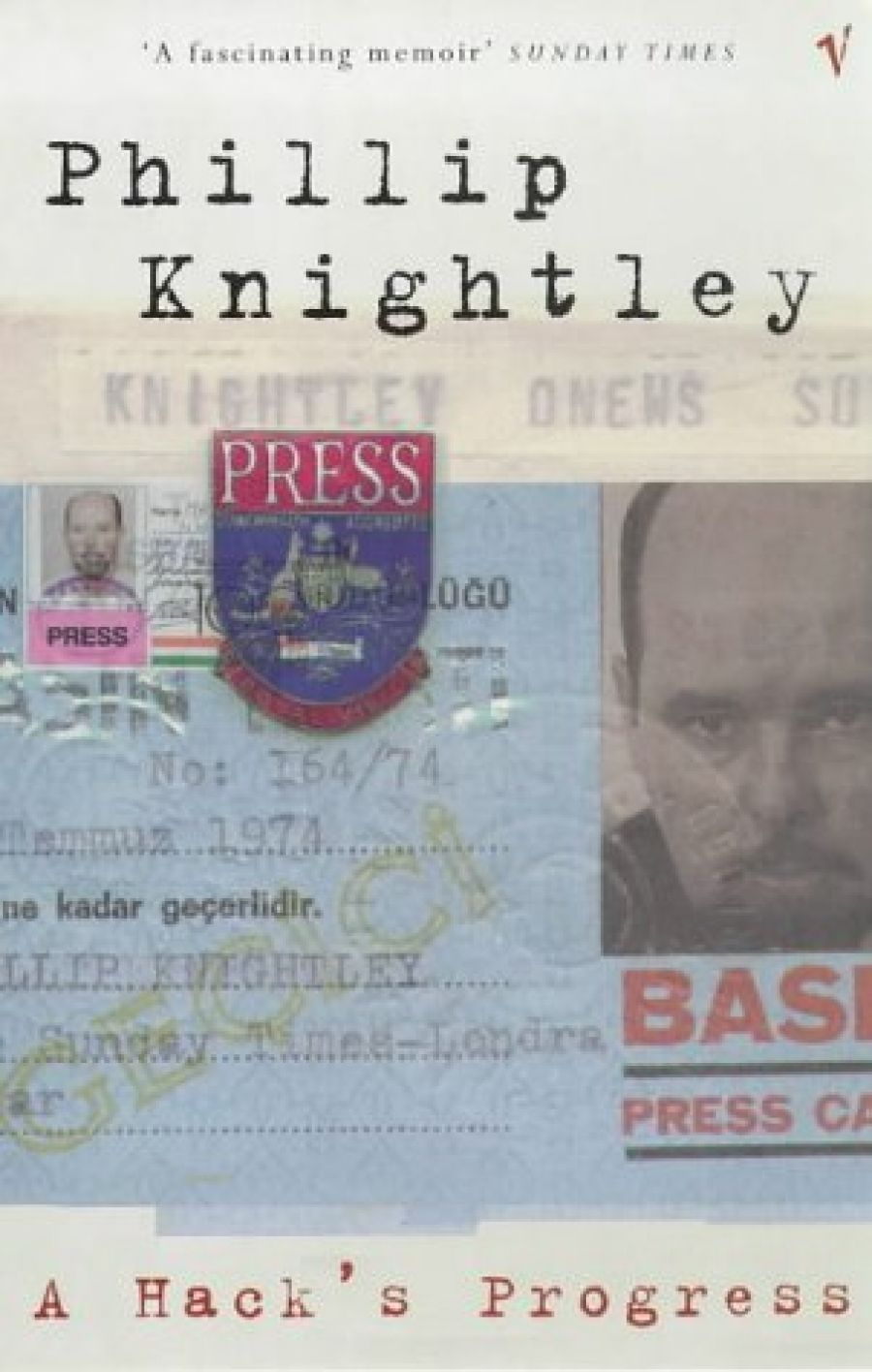

- Book 1 Title: A Hack’s Progress

- Book 1 Biblio: Random House, $35 hb, 267 pp

A Hack’s Progress is the work of an expert journalist who learned his craft the hard way. Knightley, who is perhaps best known for his book about the Thalidomide scandal, started work as a copy-boy for the Lismore Northern Star, worked his way through a variety of jobs in Australia and a number of other countries, and ended up at the Sunday Times, where he was twice named ‘Journalist of the Year’ in the British Press awards. In the process, he learned to write ‘crisp ... accurate, fresh and penetrating’ stories which can (according to the requirements of one editor) ‘successfully compete with the cat on the lap of an old lady in Eastbourne’. Knightley’s stories can also be very funny.

He is funniest when he is writing about his early life and his family. Stories like the one about the party his elderly father threw, where equally elderly guests fell in the swimming pool, fought over women, stole precious vintage wines from the wine cellar and drove their son’s car into the hedge, are told in good Aussie storytelling vein and probably owe much to his own son’s exhortations to ‘defy years of self-conditioning and write subjectively’. But no exaggeration is needed when he describes the many bizarre and hilarious episodes which occurred during his years working for Ezra Norton (‘a newspaper bar in the Citizen Kane mould’), his brief stint as a trainee South Sea Island trader, his experiences with the press corps covering a Royal visit to Australia, or his assignment to an Australian Rugby League team touring England and France – to name but a few of the many things he has done.

Dealing with more serious matters, Knightley sometimes gets a little bogged down in details or lets unfinished campaigns of his own carry him away. In his chapter on the Sunday Times campaign for adequate compensation for Thalidomide children, he examines the pros and cons of such investigative/campaigning journalism in a detailed account of the campaign and its results. He played an important part in this campaign and became very involved with the children and their families, yet his account appears to be admirably objective. It is disappointing, then, to see him disparaging the respected Australian journalist, Dr Norman Swan, but calling him a ‘a British-born paediatrician who had ambitions to be a journalist’. In 1987, Swan, in an ABC Science Show, reported on the recent, apparently fraudulent, research activities of Dr William McBride, the man who first alerted the world to the dangers of Thalidomide. After an investigation lasting six years, McBride was struck off the medical register. Knightley is quite open about his faith in McBride’s good character and about his own continuing campaign to ‘rehabilitate’ him. But he, of all people, should acknowledge Swan’s right to report such matters.

Journalism, however, is anything but unbiased. Every story has an angle which is supported by selective editing, and Knightley acknowledges this. He also questions it, especially in the chapter ‘Trial by TV’, where he describes the part the Australian media played in a police murder investigation where the suspect was eventually convicted.

Nor is Knightley afraid to be controversial or to tell gossipy stories or to demolish sacred myths. He tells the ‘true’ story of Lawrence of Arabia, Gallipoli and the Profumo affair, and demolishes some misconceptions about the spy, Kim Philby, and the KGB. And, unlike the highly flattering offerings in Andrew Neil’s recent biography, Knightley’s comments on Rupert Murdoch are refreshingly blunt.

Knowing Rupert Murdoch, Knightley saw the changes likely to come at the Sunday Times when Murdoch became its owner. He jumped ship, only to end up accepting regular freelance work back in Australia for a newspaper owned by ... Rupert Murdoch. As one former editor of the paper told him, ‘You can run from Rupert but you can’t hide’.

So this, then, is the hack’s progress. Knightley began his journalistic life working for Murdoch senior and how he works for his son. Along the way, as this book admirably shows, he has done his share of literary drudgery; he has dealt a few cutting blows, and he has shown much bone and substance.

Comments powered by CComment