- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Murray Bail has passed muster as an important Australian novelist for quite a while now. His 1980 novel Homesickness, with its sustained parodic conceit of Australian tourists forever entering the prefab theme park, rather than its ‘real’ original, was an early national venture into what might have been postmodernism. Holden's Performance, a good time later ...

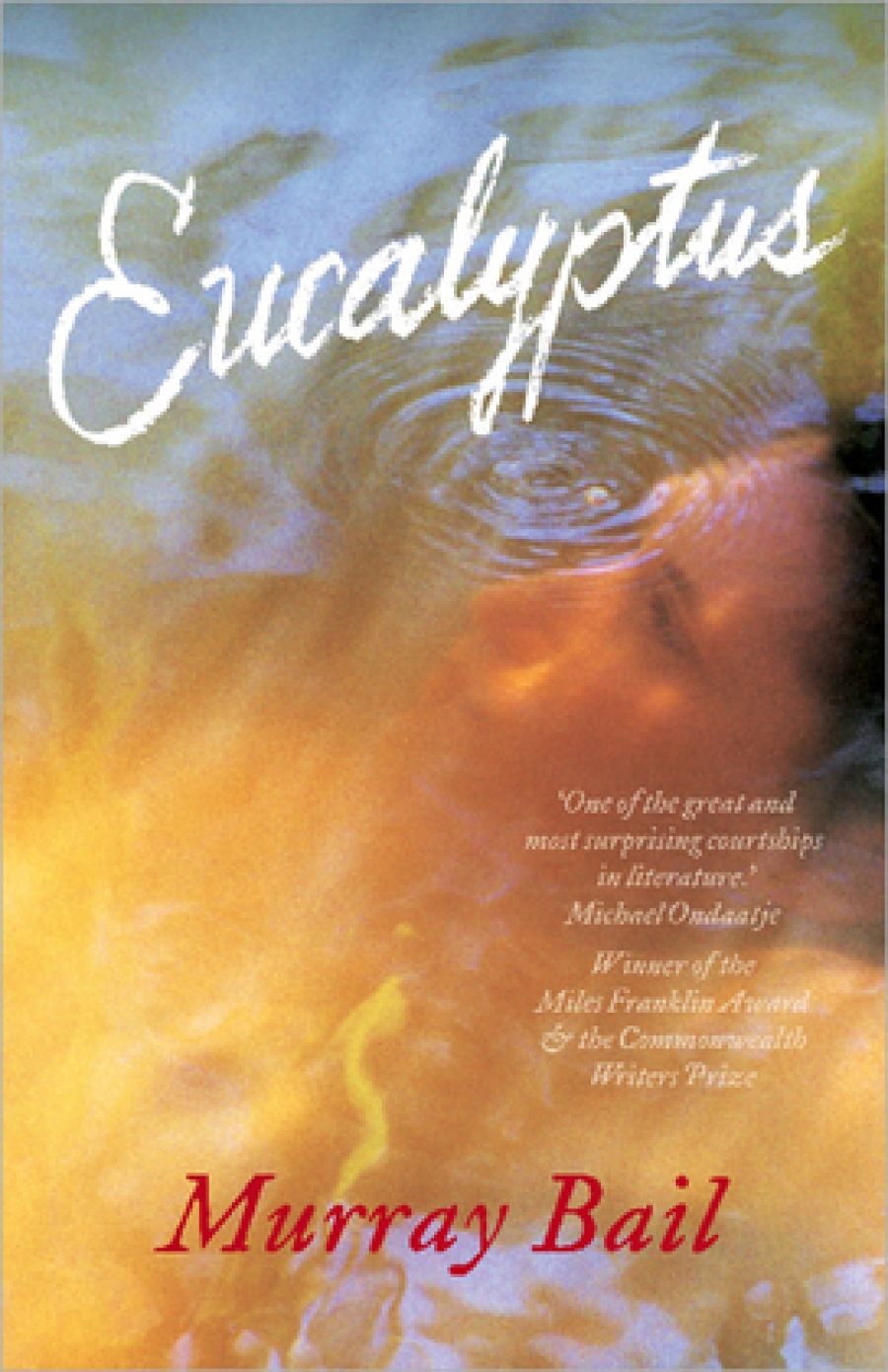

- Book 1 Title: Eucalyptus

- Book 1 Subtitle: A novel

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $29.95 hb, 255 pp

Murray Bail has always written with a bit of a clunk. His sentences sing no tune, and he is always in danger of defying the very comprehension of the reader because his material seems so undramatic.

Somehow, however, by some act of mercy or access of craft, he is, as a writer, aware of this, and his natural disabilities are transfigured into a kind of deadpan humour of nearly bottomless slyness and buffoonery. And his narrative powers, which look, at times, like a man trying to build the house of fiction out of icy-pole sticks, are salvaged by his acute sense of the corniness of every story – particularly the kind of calamitously enfeebled one he might concoct – and the fact that his artistry is therefore a critique of the very idea of structure in fiction.

And so it is with Eucalyptus, a book which is being published by Harvill in London and Text here, and which is as unnerving and deep and satisfying an exercise in pure writerly pigheadedness and will to meaning as anyone could wish for. It is a fiction – novel is scarcely the word – built on the abyss of the impossibility of writing fiction. It is, by turns, jocose and lugubrious in the manner of some anatomy five times its size and skipping and skeletal in the manner of the most ludic and elegant collection of baffling and glamorous contes. Somehow this potentially ghastly combination of styles and nearly headlong collision of methods produces a book so fresh and strange that it is like no other.

Eucalyptus is set in some mythical and timeless Australia, dun-coloured, of realistic contour and dwindled expectation, somewhere in the pre-literary early twentieth century. There is a man with a vast and comprehensive collection of eucalypts on his land. For the first, all but interminable, section of the book the trees, their genus and nomenclature and their fatiguing asinine abundance and monotony proliferate like so many unique but similar blobs in a Fred Williams painting.

The foundation of something is being laid, and it had better be good. What arouses the reader’s apprehension is that this is a slender book and the obsessiveness of Bail’s cataloguing seems set to out-whale the whale in Moby Dick. There-s a point to all this, though, because the narrative – a kind of coordinated principle of narration as a form of drama – rears its head like the serpent in the garden, quicksilver and sinister.

The man with the trees will only give his daughter in marriage to the suitor who can name every last mind-numbing genus on the property. A fellow called Cave (a name of baleful allegorical import) is a clear favourite, but then a quiet sneaky fellow appears and he tells the girl ... stories.

A non-story which has taken the form of a kind of taxonomy of nature in a language stripped of imagination is, inch by inch and bit by bit, eroticised by these discrete oases or mirages of story (are they history in the French sense too?), which this soft-voiced stranger who, we can tell, is also as dry and laconic as a gum tree – puts in the girl’s ear like the rustle of leaves and the prospect of water.

The effect is a slow, dawning wonder as love and desire are kindled by the thing in life which resembles art but makes it trivial by comparison, which is to say the power of the sympathetic imagination. There is a scene later in Eucalyptus, where the storyteller dresses the girl, that is as mute and moving in playing on archetypes, as simple in its invocation of a tenderness beyond sex, as anything in our literature.

Eucalyptus is a strange, lame, halting book, full of the trailings of false moves and resonant with the confession of ineloquence which is nevertheless a beautiful freestanding and audacious piece of experimental art. And if that sounds fearful, it is also a humane, smiling book full of the flat-voiced humour of country people who have a great twinkle of kindliness and kinship behind the tough exterior.

It reminded me of very little else I had read except perhaps for Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s Love in the Time of Cholera, though Eucalyptus is much less embellished and baroque. It is a very odd book because it is so laconic and so resolutely parochial yet it is also a book with a kind of springing musical quality, a book which delights in its self-reflexiveness as the story of the storyteller, whose story awakens the maiden, goes by leaps and bounds and at the same time reminds us of every other story (or at least their exhaustive grid).

That great critic Northrop Frye, the author of The Anatomy of Criticism, believed that myth was the fundamental unit of literature. He was a bit inclined to allow his idea of gods and heroes and mighty forces to shadow the simple idea of structure. Eucalyptus is a book which plays on the basic motifs of myth as a composer will pastiche an earlier master, but it is the structure and the glancing look of the human face which may flesh it out which is the only shadowing in which Murray Bail is interested.

This is a book which shows its scaffolding with an attractive modernity which is also unpretentious, folksy. It is a book about the naming of trees and the telling of tales. It is discernibly a book by the man who sent up Lawson’s ‘The Drover's Wife’ but it is also, complexly and ruefully, a homage to the great Australian barrenness which is its raison d’être and ordering symbology. It is among other things a complex comedy of cliché and one which is implicated in its own critique: if you like, a Drover’s Dog of a book.

The funny thing is that a book as homespun as this, as humbly and tentatively concerned with the rudiments of fiction (and the primitive narration of life), can, in the upshot, be as rich and as difficult and as moving as any modern master – any Thomas Bernhard or whoever – you might like to poke a stick at.

Comments powered by CComment