- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Even if Pauline Hanson’s One Nation Party were to self-destruct after the next federal election, which I suspect is a real possibility, it has earned itself a position in Australian political history. Hanson herself must be one of our most remarkable political figures, having risen within three years from the obscurity of a Liberal nominee for an unwinnable electorate to a politician with media coverage almost equivalent to that of the major party leaders.

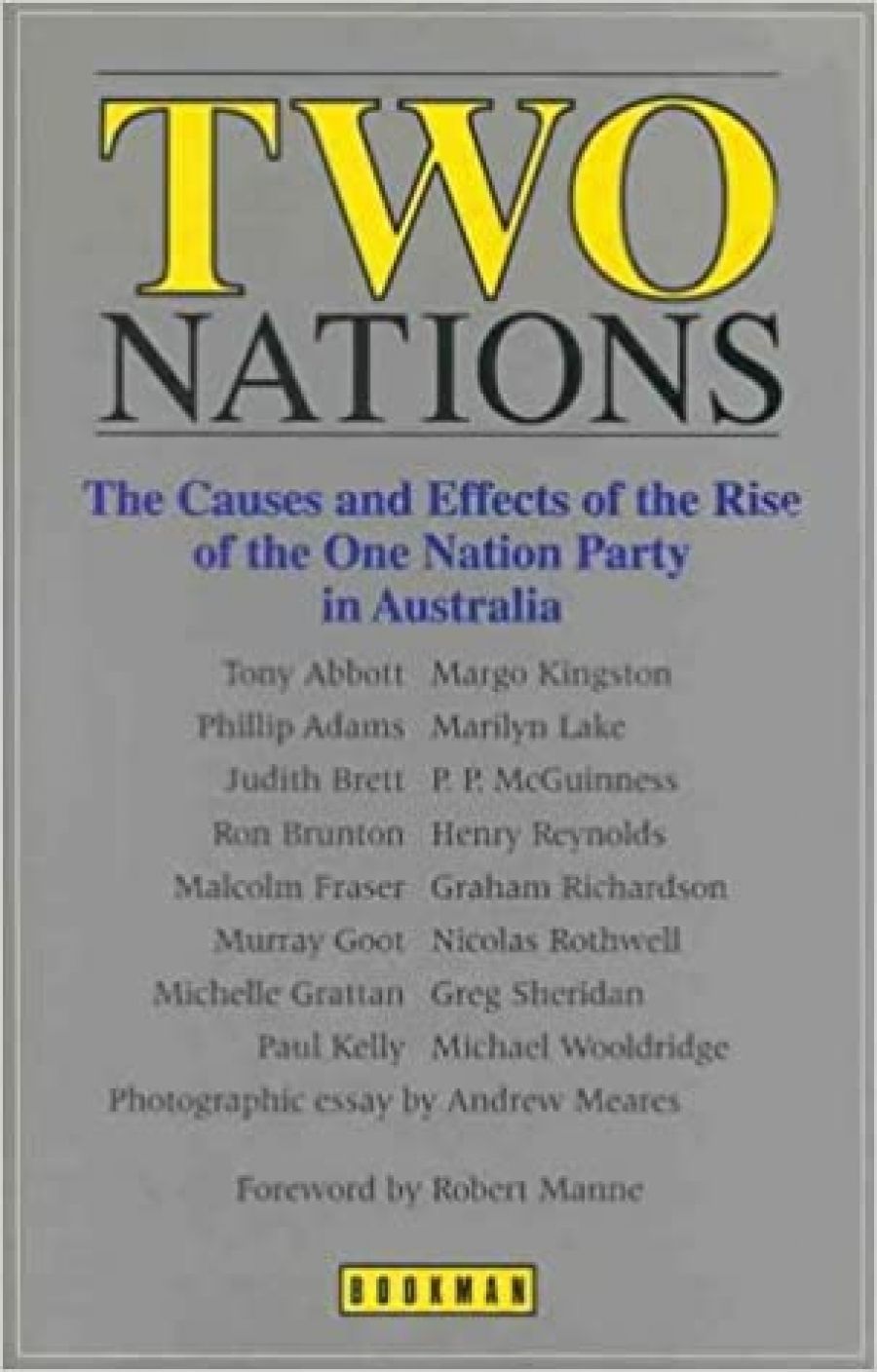

- Book 1 Title: Two Nations

- Book 1 Subtitle: The causes and effects of the rise of the One Nation Party in Australia

- Book 1 Biblio: Bookman Press, $19.95 pb, 194 pp

Hanson unsettles us because she has challenged what seemed to have been the accepted policies of the past decade, both the social and cultural changes towards a more multicultural and diverse society and the triumph of economic rationalism and a particular view of the imperatives (and advantages) of globalisation. On social issues she is ‘hard’ where the national consensus (around guns; Aborigines; immigrants) seemed ‘soft’ but on economic issues the reverse seems true: while Howard and Beazley speak of ‘the battlers’ Hanson claims she alone stands for defending traditional protection against the lure of internationalism and big business.

Understanding the appeal of Hanson has become a small industry, and this book is another step towards this. Unfortunately the book epitomises the problem as much as it offers solutions, being essentially another exercise in demonising Hanson rather than seeking to come to terms with the challenge she presents. How much more effective a collection it would be had a couple of contributors sympathetic to Hanson been asked to contribute. While the contributors divide in their explanation of One Nation’s appeal none of them speak from within, though McGuiness’s spleen towards the ‘politically correct’ means he seeks to make support for Hanson appear more respectable than that for Labor.

Not only are all the contributors are from one side of the divide, their average age is certainly well into the fifties and only one I believe is of non-Anglo-Celtic background. Mark Davis would see in Two Nations further evidence of his belief that a small group of the tried and true middle aged dominate public debate in Australia, and in the case of this book he would be right. It is particularly odd that while opposition to Hanson seems a requirement for inclusion the unnamed editor has not sought the voices of either Aboriginal or Asian Australians. How much more interesting a book this would have been had he (she?) discarded some of the predictable contributors in favor of, say, Lillian Ng, Roberta Sykes, Christos Tsiolkas, and Mischa Schubert.

There is something of a consensus amongst a number of contributors that a gap has emerged between two groups in Australia, a gap which Michael Wooldridge calls that between the ‘policy culture’ and the’ community culture’. (Wooldridge’s contribution to the book suggests he may be the only intellectual in the current cabinet, a position one imagines must leave him fairly isolated.) While the latter term is rather odd, the theme recurs in a number of essays, and is developed in Robert Manne’s introduction.

Just why this gap has occurred is less clear. The contributors appear to divide between those who want to blame Paul Keating and those who suspect the question is more complex. Thus for Ron Brunton, Hanson is supported because of ‘the arrogant and intolerant way that Keating and his supporters were promoting policies supposedly designed to ensure racial tolerance.’ The same claims are echoed by Tony Abbott and P.P. McGuiness. Given the venom with which Keating’s ‘vision’ was consistently attacked on some of the highest rating radio programs in the country I have never understood the claim that during Labor’s period in office the politically correct drowned out free speech, but then I did not suffer the same brutal silencing of my views. obviously encountered by McGuiness and Abbott.

The contrary view, which sees Howard as far more culpable in his failure to meet the challenge of Hanson, is particularly held in the press gallery, and is argued here by Michele Gratton, Greg Sheridan, and Paul Kelly. The argument seems to me persuasive but it does not go far enough: given Howard’s lack of charisma I rather doubt whether his opposition would have made that much difference, though it would certainly have helped our image internationally.

Interestingly some on the left also lay some blame on Keating, but for his economic rather than his social policies. This view attributes support for Hanson to the discontent and unease felt by large numbers of Australians who have been marginalised by ‘globalisation’, whose jobs and security seem threatened by the bipartisan embrace of big business and overseas investment. As Judy Bren writes: ‘Nearly two decades of economic liberalism have left many people worse off.’ To which she adds a further factor, namely the rise of professional politicians and a decline in the representivity of the political system as Parliament contains fewer and fewer people from outside the ‘policy culture’. Henry Reynolds supports this view in arguing that Hanson represents protest both ‘against politics as presently practised and against incumbent politicians’.

From rather different positions both Nicolas Rothwell and Marilyn Lake point to the sexiness of Hanson, the appeal, as Rothwell puts it, of ‘the potent scent of late-blooming sensuality, mingled with the sharp pheromones given off by all leaders who cloak themselves in cults of personality.’ Lake’s piece, ‘Virago in Parliament, Viagra in the Bush’ manages to be both witty and perceptive, a welcome combination.

It is too early to be sure, as some of the contributors are, that One Nation will survive, or even have the role in Australian politics of the D.L.P. or the Democrats. Indeed Hanson herself may well vanish from Parliament at the next election, which some have suggested may be the intent of her chief of staff and putative Senator elect, David Oldfield. Even amongst the groups most attracted to Hanson – less educated rural men – most still support the traditional parties, and the current tax debate may well drown out the ratbag of racial and social grievances which Hanson tapped during the Queensland election.

In terms of understanding the potential and support of One Nation this book is a curate’s egg, good in parts. I admit that I particularly liked the contributions of my colleagues (Brett, Lake, and Manne) but I hope this represents an objective assessment of the difference between analysis and polemic rather than a form of academic protectionism.

Comments powered by CComment