- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

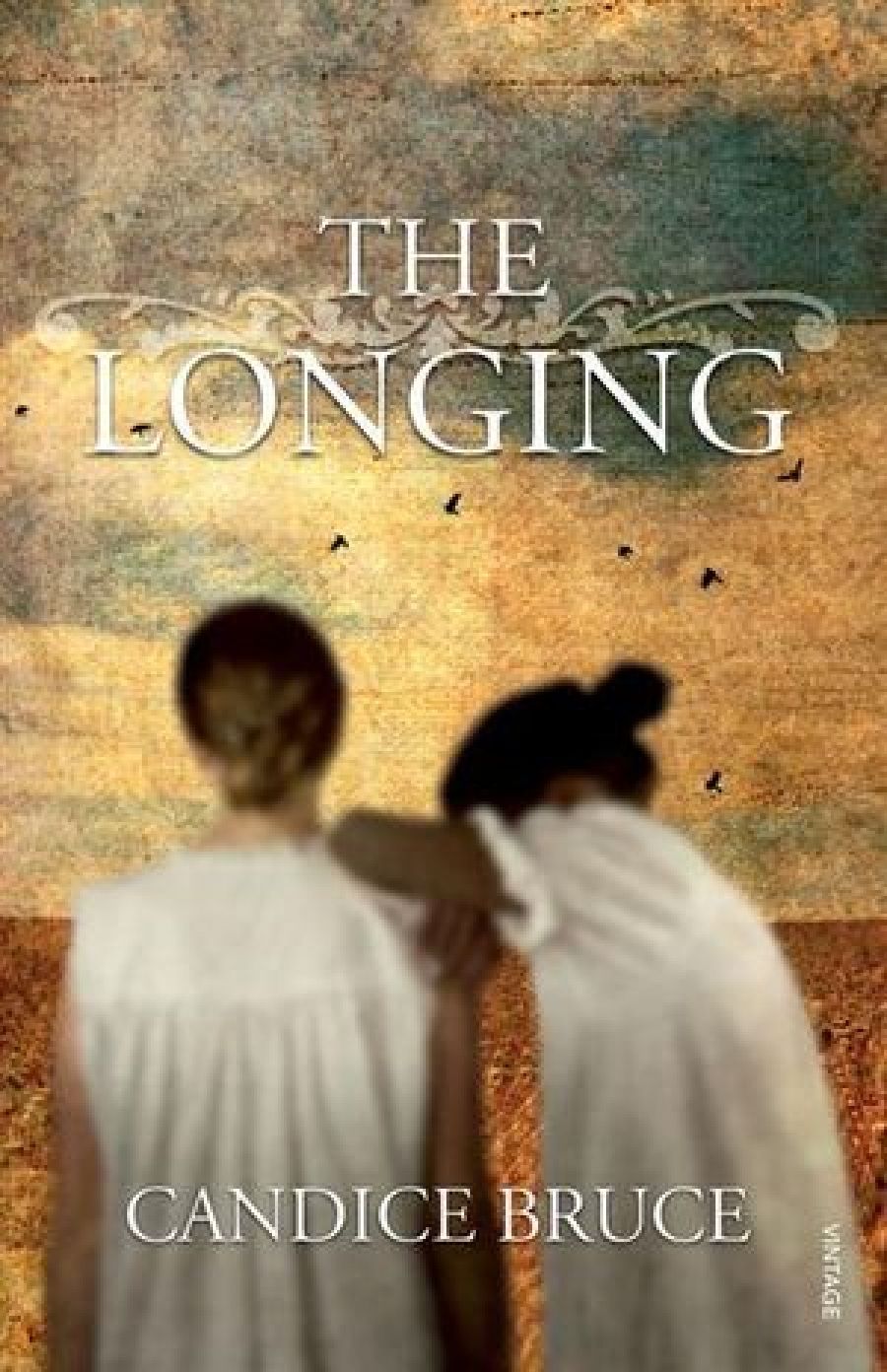

- Custom Article Title: Francesca Sasnaitis reviews 'The Longing' by Candice Bruce

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The Longing is an ambitious first novel. Set in the Western District of Victoria, with parallel narratives in the mid-nineteenth century and the present day, its principal theme is the occupation of Gunditjmara country by white settlers, and the decimation of Indigenous tribes. Novel writing is, of course, an act of imagination, and writers should be commended for their research, tenacity, and inventiveness, but I cannot ignore the social and political implications of this particular story, and cannot help but be alert to the authenticity of its three main voices and the sentiments they express.

- Book 1 Title: The Longing

- Book 1 Biblio: Random House, $32.95 pb, 360 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.booktopia.com.au/the-longing-candice-bruce/book/9781864712704.html

As an experienced art historian, curator, and writer – author of two highly respected books on the nineteenth-century landscape painter Eugene von Guérard and numerous other scholarly publications – Candice Bruce is aware of the difficulties of ‘a non-Aboriginal writer writing a story about an Aboriginal woman and her friendship with a Scottish settler. Writing about massacres and racism and frontier violence, but from an Aboriginal woman’s point of view, as well as that of a Scotswoman.’ Even though Bruce was advised by Vicki Couzens, a Gunditjmara/Keerray Woorroong artist, and while admitting that I find the voice of Louisa Leerpeen Weelan the most convincing in the novel, I hear a jarring note: Bruce has difficulty combining pidgin with articulate English, particularly when direct conversation bleeds into recollection.

Vicki Couzens also gave Bruce a dictionary of local dialects through which she discovered ‘language’ and a way into her Indigenous character. Meerreengan for country, or poothong, pakap, paloot, pooteeyt, koorrameet, ngayook, and kaleenya, for various bird species, add brilliant colour, but Bruce does not fully utilise these rhythmic words to distinguish Louisa’s voice. The sustained musicality found in Kim Scott’s That Deadman Dance (2010), which imitates the rhythms of Nyoongah language and that of the sea, is missing.

The Longing begins in 1857 with Louisa making a possum skin cloak in the traditional manner, scoring and painting the skin with marks that tell of her country, clan, and journey. She is preparing to depart.

In 2002 the contemporary narrator, Cornelia Bremer, a harried young assistant curator, is painstakingly cataloguing a series of sketches by S.P. Hart in the Prints and Drawings Room at the National Gallery of Victoria. When the senior curator is involved in a car accident, Cornelia is charged with seeking out a landscape painting by Hart, a view from the verandah of the Strathcarron property, where the painting and the descendants of the original settlers, the MacRories, still reside.

As a structural device, the contemporary commentary on the nineteenth-century narrative is only partially successful: Cornelia’s discoveries tend to echo, rather than advance, the narrative in any significant way. Her story is the least engaging of the three, and her relations with the feuding MacRories seem stilted and arbitrary. The contemporary characters remain two-dimensional despite the mystery surrounding the death of Duncan MacRorie’s brother, and the greater mystery surrounding the provenance of certain drawings in the MacRories’ collection. The dialogue is particularly unconvincing, and Cornelia comes across as excruciatingly self-aware, inexperienced, at times a little thick. An ex-lover accuses her of preferring the safety of the past to the present. Perhaps the same ‘accusation’ can be levelled at Bruce.

The twenty-first century sections work best in descriptions of landscape and art – clearly Bruce’s forte – and in the transcriptions of Ellis MacRorie’s diaries from the mid-nineteenth century.

In 1855 Ellis, the depressed and disappointed wife of wealthy pastoralist Alexander MacRorie, muses on her past and on the possibility of happiness with visiting artist Sanford Hart. Having known little of love or amusement, Ellis is easy prey to a flirtatious gentleman. Hart woos her with ‘umbra and penumbra. Such interesting words.’ She is neither a bad person nor a bad mistress to her servants, but she is self-absorbed, desperate, naïve, and weak. ‘Shadows are not black; they contain the hue of the object itself,she can hear him say,’ but Ellis pays no attention to words fraught with innuendo. Even when she discovers Hart’s shameful peccadilloes, she ignores the truth. The consequences are melodramatic, to say the least, and plunge the narrative into high Gothic romanticism which sits poorly with its otherwise pastoral realism.

As Ellis makes a fool of herself over the painter, her servant and sometime confidante, Louisa, watches. She too muses on her past, which is significantly more horrifying than Ellis’s passive decent into melancholia. Louisa has survived the massacre of her clan, forcible separation from her first child, rape by white men, and the resultant birth of a second child whom she finds hard to love. She has suffered every possible degradation and humiliation, and has even been renamed to please the colonisers. Louisa might have remained a cipher for the dignified ‘noble savage’ had Bruce not also endowed her with an observant eye and an acerbic tongue. Bruce has particularised Louisa’s grief; her recollections are filled with small moments of intimacy, poignant details, and everyday grumblings. She has given Louisa the fortitude and resolve of the repeatedly bereaved.

Bruce is still learning the skills of dialogue, characterisation, and plotting; she does not always manage the voice of a nineteenth-century character without twenty-first century anachronisms creeping in. As she says through Hart, ‘Art is the struggle between the physical eye and the eye of the imagination.’For the writer, too, it is a struggle to maintain that elusive balance between detailed description and evocative disclosure.

Comments powered by CComment