- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Gough Whitlam is idolised, Bob Hawke respected, and Paul Keating admired, but Barry Jones is undoubtedly the most loved by the Labor party rank and file, a lovability which puzzled many of his colleagues in the Hawke government (1983–91). Insofar as they recognised it, they qualified it – labelling him ‘a loveable eccentric’ – a characterisation of ...

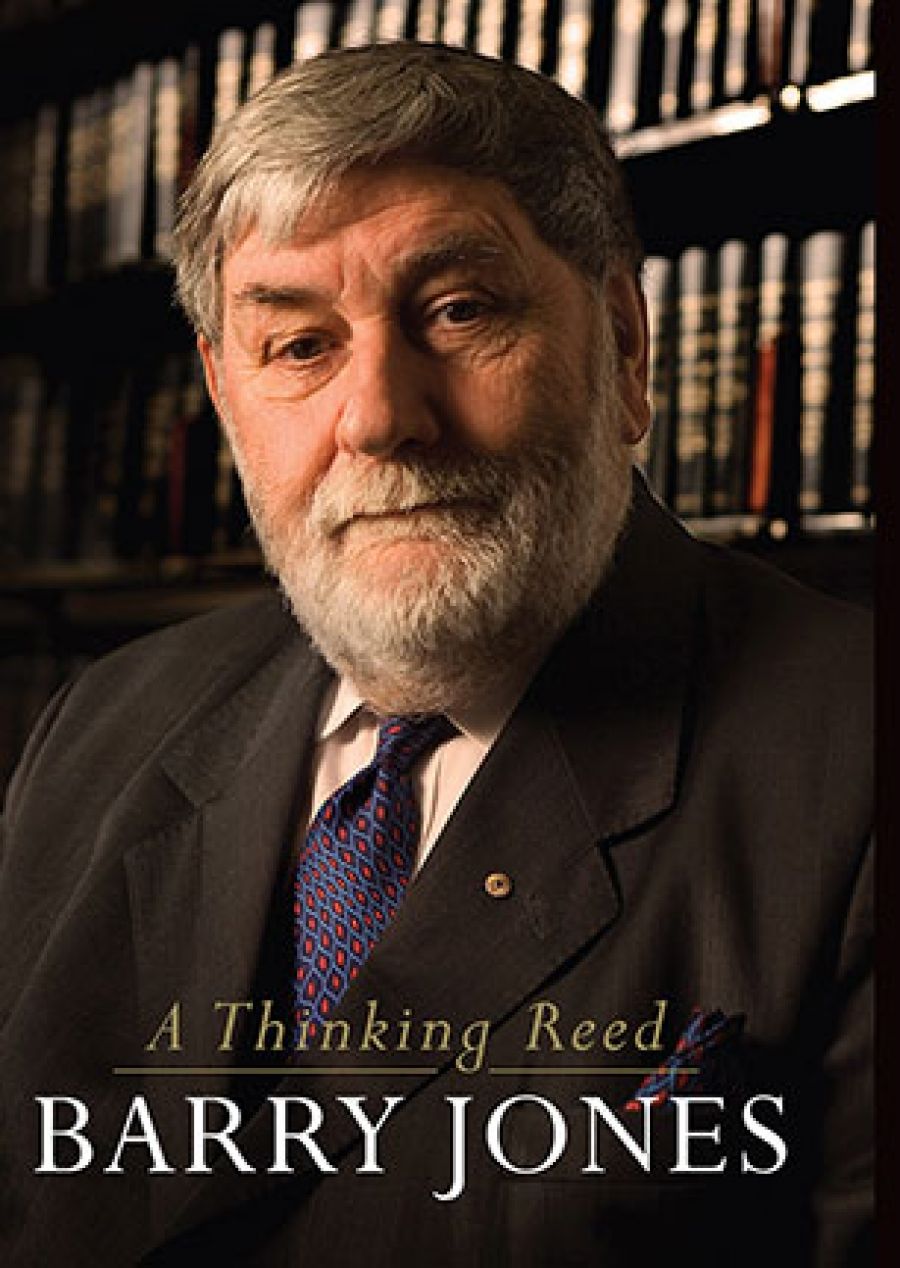

- Book 1 Title: A Thinking Reed

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $55 hb, 572 pp, 978174114387X

Jones grapples better with ideas than with people, and the result is an autobiography dealing more with the life of the mind than with the political life. His ardour for aesthetic experience is contagious, though his lists of favourites infuriate: in music no Sibelius – despite a visit to widow, house and grave; in opera no Handel; in film no Almodóvar; and what happened to twentieth-century American novelists apart from Thomas Pynchon? But perhaps the lists are simply a heuristic device to open the floodgates so that we may debate his enthusiasms.

His account of his spiritual quest – the odyssey of ‘a sceptical Christian fellow traveller’ – is moving and honest. Over a lifetime, he has drifted from a Methodist youth to ‘an increasingly problematic camp follower’ of the Uniting Church. Not confident enough to be an agnostic, distrusting rationality when it turns into dogma, recognising the numinous, he ‘hovers on the margins between religious experience and aesthetics’. He is sustained by the writings of the French philosopher Blaise Pascal, with whom he identifies and of whom it was said that ‘he touched God behind the veil of scepticism’. I know of one friend who has found this chapter an antidote against grief.

The ‘mind in action’ could well be the title of one of the best chapters in the book: his account of his role in the ultimately successful campaign to end the death penalty in Victoria. For once, his talents meshed: an absolutist issue on which there could be no shilly-shallying and on which he used his indefatigable skills as agitator and his eloquence as advocate. Here his prose catches fire, and it is a pity that a climactic paragraph on page eighty is ruined by poor editing, which contradicts his argument. He is right to feel ‘a profound satisfaction’ with his role in this cause.

Jones does not feel the same satisfaction about his political career – ‘challenging, rewarding and often depressing’. Yet he began with a considerable advantage – his public recognition as Australia’s quiz king on Bob Dyer’s Pick-a-Box show, on which he writes with gusto and much detail. He notes, perhaps immodestly, that ‘Bob Hawke and I had one thing in common … we were quite atypical on our side of politics in gaining public recognition before entering parliament’. Yet this high public profile as a ‘quiz kid’ was perhaps a mixed blessing, for he admits that when seeking pre-selection, ‘I grew a beard to make old Pick-a-Box publicity photographs obsolete’.

The disappointment of the political chapters is that the autobiographer as politician is too often absent. He is there as philosopher, historian, detached observer, but rarely as a living, battling politician. He is perceptive on the evolution of his political philosophy and on the influence of individuals on his own political engagement. Yet what we get on the early period is a history of the Byzantine labyrinth that was Victorian Labor politics in the 1950s and 1960s. There are only fleeting appearances by Jones, drawn like a moth to gadflying with the great: H.V. Evatt, Arthur Calwell, and Gough Whitlam. The impression left is that of a dilettante agitator.

Jones provides a chapter on the Hawke regime that is a succinct and balanced assessment of that government. Of Hawke he writes that ‘he changed the Australian economy more than any other Prime Minister, transformed how governments operated, and transfigured the political culture, especially in the ALP’. However, he concludes, as I have elsewhere, that it may have been a ‘Faustian bargain’, for in the process ‘the party lost, if not its soul, then a clear sense of its own beliefs’.

While this chapter is entitled ‘Inside the Hawke Government’, it reads like an outsider’s assessment. We never learn how Jones felt at the time about Hawke’s revolutionary direction of the party. Did he work within the government or the party to expose the ‘Faustian bargain’? Nor do we learn where he stood in the leadership battles that convulsed the party in those years. Was he with Hayden or Hawke in 1982–83? Did he vote for Hawke or Keating in the leadership ballots of June and December 1991?

Although Jones was the ALP president from 1992 to 2000, we learn more about how he got the job and staved off rivals than what he achieved in those eight years. Did he have an agenda or a set of ambitions as president, particularly after the fall of the Keating government in 1996? Today, Jones waxes eloquent about ‘the entrenched feudal structures of the factions’ in the Labor party. Did he attempt to do anything about this during his years as president? Was the presidency little more than, in his own description, a cross between ‘an industrial chaplain, grief counsellor and ombudsman’? Surely an eight-year tenure as the party’s formal head, the longest period in the party’s modern history, deserves more than eight pages in a 500-page autobiography.

The one chapter in which Jones does develop a full personal account is the one dealing with his seven years ‘ministering to science’ from 1983 to 1990. The Ministry for Science and Technology was seen as ‘a political death valley’, and for Jones it became a veritable via dolorosa along which he wanders, wallowing in self-pity. True, he had a tough time as minister: he was ‘specifically disinvited’ to the 1983 Summit; his sunrise industry proposals were ‘ambushed’ in 1983; his National Technology Strategy was ‘sabotaged’ in 1984; his National Information Policy was ‘frustrated’ in 1985. In 1984 Technology was ‘taken from me’, while in 1987 Science was gutted and redistributed, most of it being incorporated in the mega-department of Industry, Technology and Commerce. Jones felt he was left ‘the back legs of the horse’.

He blames everyone but himself. He was surrounded by ‘a strongly anti-intellectual mood ... with a narrowly instrumental view [of] science’. His prime minister never ‘had never taken science seriously’, his colleagues ‘marginalised and discredited [him]’, and his views were ‘detested’ by the Canberra mandarins. As for his potential allies, the university vice-chancellors were ‘a pusillanimity’ and the scientists ‘wimps’. He does acknowledge that he failed to network adequately, did not cultivate journalists and lacked the killer instinct.

It was not just the killer instinct he lacked but most of the know-how required for a successful minister. He could rarely bring himself to lower his sights from his often prescient visions to the nitty-gritty of the here and now. He would respond to colleagues’ specific criticisms by reiterating his overarching generalisations, as though any particular criticism reflected on his grand assumptions. He could not be persuaded to prioritise, to advance to his goals by steps, and any suggestions of compromise were viewed as tainted. Above all, in matters of science at least, he lacked any sense of collegiality; his loyalty lay not to the government but to his science constituency.

However, when he rises above his lamentations, he notes some real successes. He preserved the CSIRO from dismemberment; he established the National Bio-Technology program and secured much needed monies for meteorology and Antarctica. And he has left behind tangible monuments: the National Science and Technology Centre in Canberra; a Barry Jones Bay in Antarctica, and a rare prehistoric marsupial named in his honour, Yalkaparidon jonesi.

In such an abundant life story, it is easy to miss the hollow at the heart of it, and the private Jones eludes discovery. There is much promise at the beginning: the precocious child views his banal parents, locked in a probably loveless marriage, with an unblinking eye: a father, ‘with no assets other than personality, a way with words and an incurable but unfounded optimism’; an emotionally inhibited mother, a drifter through life, who ‘read little, never listened to music and rarely went to theatre or film’. Refuge is found in a sympathetic and musically talented grandmother, and in a tough-minded and kindly great- aunt. There are searing revelatory flashes but no sustained confrontation with his family; rather, the promise is leached away in leaden paragraphs on innumerable ancestors and by an early escape from intimacy into the world of the mind and politics. At the age of six, he ‘followed the Munich crisis … anxiously’; by eight he was deep into the libretto of The Ring of the Nibelungs.

Of course, one does not expect a political autobiography to detail the writer’s intimate personal life. One does not demand of Hawke that his memoirs delineate his liaisons. But of an autobiographer who writes what he proclaims is ‘an odyssey …in search [inter alia] … for love … [and] self-knowledge’, much is expected. And thus we come to the problem of the missing wife. In a moving afterword, noting her death, Jones writes that his relationship and marriage to Rosemary Hanbury had a ‘centrality in both our lives [which] was unquestionable’.

Yet searching for Rosemary Hanbury is like a mystery novel in which evasions and odd temporal juxtapositions litter the trail. She first turns up in the text on page eighty-six, without explanation but listed as ‘teacher’ in a roll of members of the 1962 Anti-Hanging Committee (Victoria). She returns twenty pages later, still without explanation but now coupled with Jones as ‘Rosemary and I’. On page 119 we learn to our surprise that they had been married sometime before December 1961, i.e. before all the references already noted; for they embark then on ‘a belated honeymoon’ on the SS Mariposa, one of his Pick-a Box prizes. We find later that they had both joined the St Kilda branch of the Labor Party together in 1950. Only two of some ten references throw any light on her personality. Both suggest she was a woman of character and intellect: quotes from a ‘scorching reproof’ she wrote to Arthur Koestler, and her provision of the title ‘Sleepers, Wake’ from a Bach cantata.

The reader, frustrated by the elisions of his private life and tired of the self-serving of some of his political observations, then comes to the brilliant final chapter, ‘Years of Exile’, a profound meditation on the way we live now, structured around the three shattering events that have characterised the political life of the last generation: the collapse of Keynesianism; the implosion of the Soviet empire; and the coming of jihadi terrorism. The first saw ‘private benefit displace public good as a policy objective’; the second seemed to render left politics ‘obsolete’; the third ‘dethroned reason … debased democratic practice … so that the rule of law was disposable’. The tone is apocalyptic, the language incandescent and the mood sombre, for not only have these events shaped our times but they have undermined the social democratic verities on which Jones has based his life.

Comments powered by CComment