- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Architecture

- Custom Article Title: The odd couple

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The odd couple

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Don’t be fooled by this book’s splendid appearance; it’s not to be left on the coffee table. It is an excellent compendium of cultural, political and social history, complementing Philip Drew’s The Masterpiece (2001) and Françoise Fromonot’s superb study, Joern Utzon et l’Opéra de Sydney (1998). It also establishes Anne Watson as a distinguished historian, both in her own contributions and in her orchestration of others. She has understood that there can be many sides to such a story; the way politics and culture have been entangled in this building’s history gives rise to questions worth unpacking indefinitely.

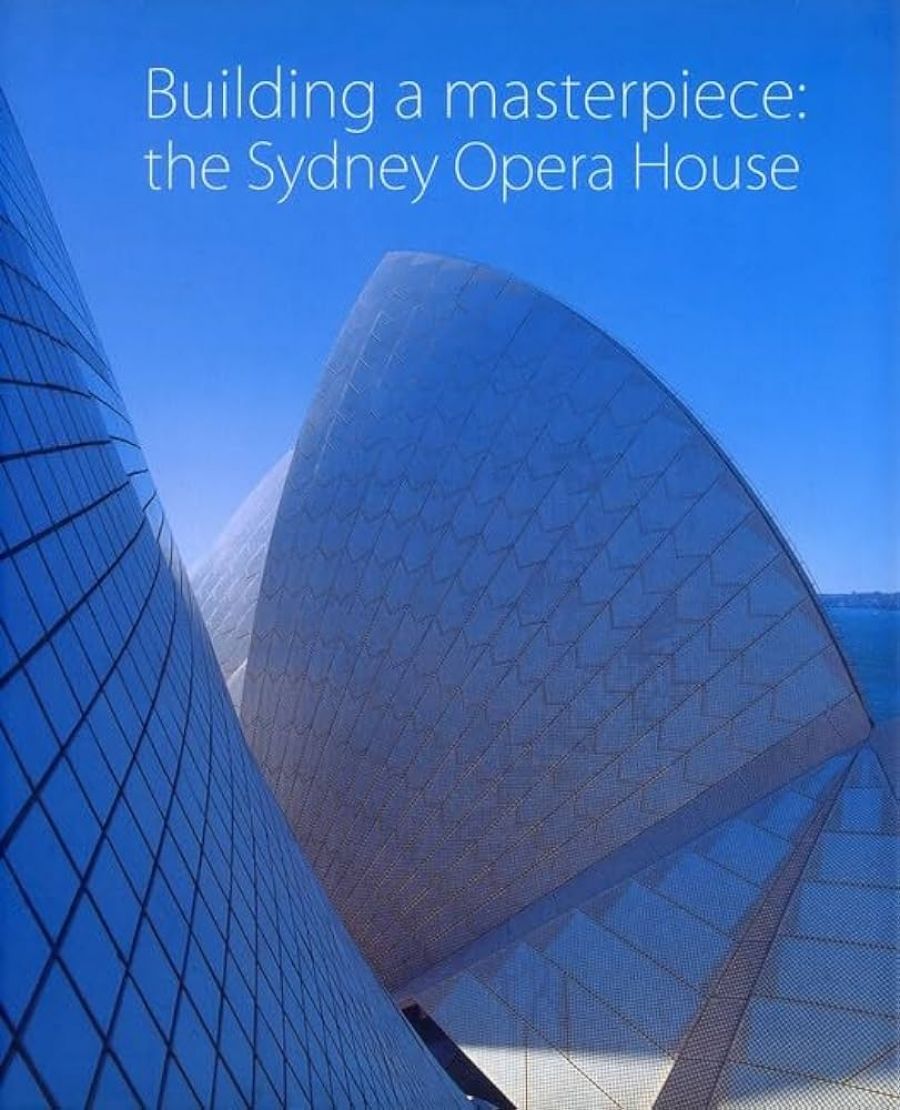

- Book 1 Title: Building a Masterpiece

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Sydney Opera House

- Book 1 Biblio: Powerhouse Publishing, $55 pb, 191 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

The chapter by David Taffs, of the Ove Arup engineering team, amounts to an excellent short history of computer use in the late 1950s and early 1960s. At the outset of the project, engineers were still using logarithmic tables and slide rules. Computers appeared, analogue devices giving way to digital, and Arups began analysing Utzon’s startling schemes. Huge machines, with names like Pegasus and Orion, churned away for years on calculations for workable geometries. The beautiful free-form wings of the first sketches, devised for the magical malleability of shell concrete, were never going to stand up. From 1958 to 1963 parabolas evolved through ellipsoids to circular arcs. Then abruptly – short-circuiting his engineering collaborators in a way which inevitably gave offence – Utzon hit upon the spherical geometry which made possible the building as we have it.

Robert Geddes’ essay is particularly generous. He was part of the consortium which won second place in the design competition; while that design now looks ugly, in a peculiarly 1950s way, his chapter is a great conducted tour of optimistic postwar architectural dreaming by Louis Kahn, Matthew Nowicki, Nervi and others. Drew again expounds the building’s special eloquence, with the break between the earthbound podium and the soaring vaults repeating ‘the ancient sacred distinction in temples of a symbol pointing from earth to heaven’.

Utzon found an ideal collaborator in Ralph Symonds, chemist, engineer and plywood manufacturer, and until now an unsung hero of the story. As Philip Nobis writes: ‘he had a galloping intellect and a breathless rate of ideas coupled with a fearless capacity to put them into action.’ Uniquely in his industry, he turned out plywood in long sheets, each more than fifteen metres long, thus reducing the need for joints. For Utzon, this was dream technology, exactly what he needed as he worked on plans for Stage Three, the interiors, trying to meet the demand for variable acoustics. The client, the state of New South Wales, required from him a major hall capable of serving both symphony concerts and opera. With expert acousticians in Germany, and with the marvellous capacities of plywood, Utzon found solutions, as researchers such as Fromonot, Nobis and Peter Georgiades have by now made clear.

Symonds was killed in a boating accident in 1961, when Utzon had already lost two other crucial supporters. Petty scandal-mongering had compelled the great conductor Eugene Goossens to leave the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, and Australia; this episode of professional martyrdom prefigured Utzon’s forced departure exactly ten years later. Watson identifies Goossens’ major role in the story; from his arrival in 1947 he had been determined that Sydney should have a real centre for its music. For that he had manoeuvred untiringly, and convinced John Joseph Cahill, then Labor premier of the state.

Cahill, a shrewd, toiling little Catholic right-winger, never pretended to be a man of culture, but he wanted the best for his city. He also had the rare gift of knowing excellence when he saw it, and of acknowledging worlds beyond his own limits; Utzon himself has always paid him tribute. The photograph from 2 March 1959, in which he and Utzon together lay the building’s foundation stone, shows the oddest couple imaginable. Cahill died only months later, while the hard-fought legislation was still being devised.

With those men gone, the obstacles could only multiply – not least because very few, outside his youthful atelier, had any idea of Utzon’s guiding concepts. He worked according to a transdisciplinary, holistic method in which design, manufacture and construction proceeded interactively together. This came out of European practices, which contrasted sharply with the traditional British–American–Australian mode of organising design first and handing finished plans to the contractors. Thus the problems were in a sense multicultural ones; this was always a migrant story. The deep hostility to Utzon, both from the implacable minister Davis Hughes, and equally from sections of the architectural profession, had everything to do with resentment of the foreigner.

Repeatedly, Hughes refused Utzon the funding needed to build the plywood mock-ups from which workable plans could have been derived. At the same time, the minister continued to demand definitive plans on paper. That impasse led to the forced resignation, the frantic attempts at retrieval, the mass protests. The crisis on the site, where the fabulous vaults were by then rising into the air and the tiling was under way, politicised an urban community; the pro-Utzon march of 3 March 1966, opened the streets for the protests against the Vietnam War.

Utzon left Australia with his family in late April; then in Denmark, firmly believing he would be called back, went on working on Stage Three. The unavailing fight for his return continued in Sydney for two years, marked by rallies and petitions, and by Utzon’s own poignant pleas to the government. Some tried to broker collaborations with those who were trying to fill his shoes, the consortium of Hall, Todd and Littlemore (HTL). The role of the Royal Australian Institute of Architects’ NSW Chapter (RAIA) was thoroughly discreditable; they equivocated and colluded. Had the RAIA’s leaders acted in professional solidarity, Davis Hughes could have done nothing. Neither time nor money was saved in the end, and much was lost. When Utzon was forced out with his team, more than five years of cutting-edge research and invention, at the meeting points of acoustics, architecture and construction, went to waste.

Toward HTL and others, Utzon has been remarkably forgiving; his magnanimity may be part of his remarkable survival. His re-engagement, in the building’s current refurbishment, has been taken as reconciliation, and this book is a grand salute, flags flying. But we should be clear: masterpiece or not, the building is radically flawed. The inside doesn’t understand the outside at all, and the glass walls are jarringly incongruous. A symbol, if you like, of a deeply divided nation – the outside is (mostly) exhilaration, the foreign architect’s response to a place where sky and water meet the city, and beyond to an ideally hopeful Australia. The inside is let-down, loss, timidity: dated kitsch.

People don’t have to theorise major symbols in order to feel their force; it’s not for nothing that the story is told and retold, filmed and sung. By xenophobia, meanness and blinkered fear of difference, a great work was denied its totality. Sound familiar?

Comments powered by CComment