- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Burchett – a committed man or a bought stooge?

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

There is in the annals of Australian media reporting of international affairs, a dominant tradition of what one might well describe as the ‘Biggies’ school of journalism. ‘Pace’ Damien Parer, Blanche D’Alpuget, John Pilger, Peter Hartings and others, the ‘Biggies’ school has provided a paradigm broken but rarely.

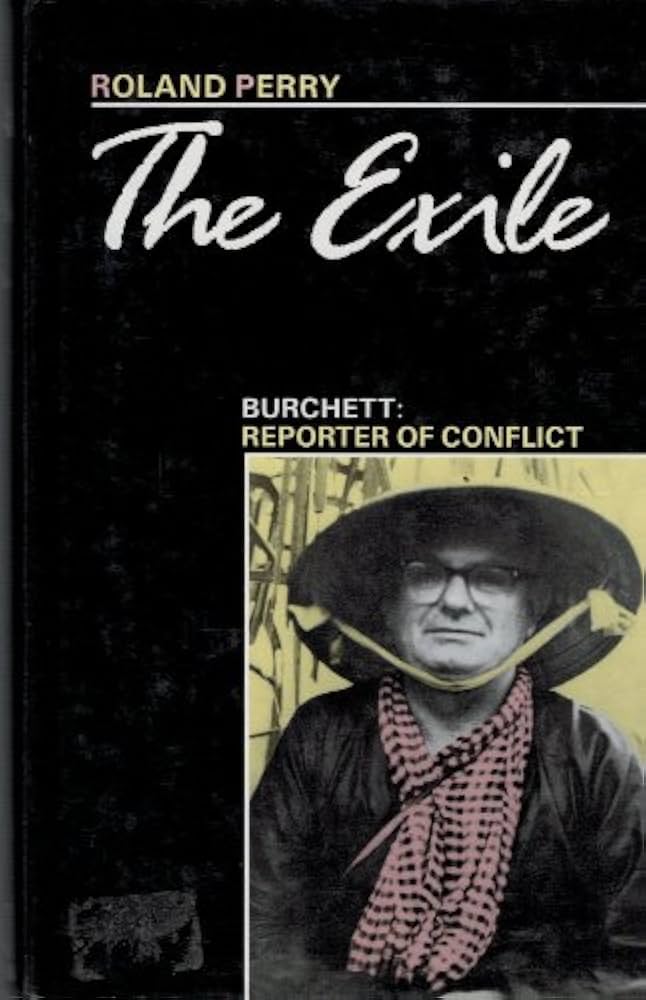

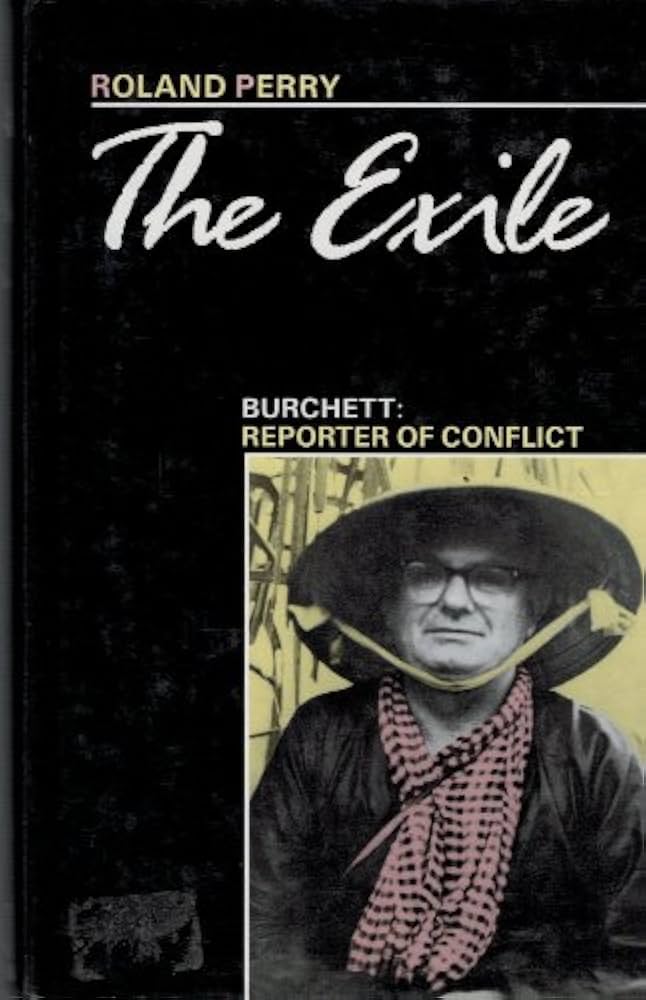

- Book 1 Title: The Exile

- Book 1 Biblio: Heinemann, $24.95 hb, 368 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

There are two, and only two, Australian journalists of serious international repute who never were to belong to the ‘Biggies’ school. They are of course, Morrison ‘of Peking’ and Wilfred Burchett of ‘Vietnam’. Both of them ‘sui generis’, genuine independent products of their times, who by extraordinary personal diligence and from lessons often dearly learned prior to their entry into the profession, were equipped to engage with and to interpret their items, more significantly from the Asian continent. These ruminations were very much in one’s mind when reading through Roland Perry’s new book on Wilfred Burchett: The Exile, released this month.

The great problem of course with Wilfred Burchett’s life and works is that one is forced, as a co-Australian, to measure one’s own understandings of Australia equally, and quite precisely, over many of the same eventual issues at the same time. No luxuries of distance are afforded in the matter. This indeed is the central thesis of The Exile, and in choosing such a ‘modus operandi’ to account and assess his subject’s life, the author has trod a difficult path.

To give credit where it is due, this recorder has taken on himself a monumental task. At one level he is close to succeeding; in a way simply by having tackled the task at all. Anyone attempting a biography of Wilfred Burchett has a lot to contend with. Time has not softened in anyway the sharp edges on the events or issues central to Wilfred Burchett’s life. Or indeed, of the values that he set out as a journalist and quite formidable human being to represent by means of his career.

Burchett it was after all, who brought to the world the very first on-the-spot views of Hiroshima’s post-atom bomb devastation. And, even as he was able by being there to discern, and to denounce the dreadful gravity of ‘radiation sickness’ as the larger threat, and to be as moved by it as to issue his famous ‘warning to the world’, he was most crudely and savagely traduced by the US military as being a ‘Jap agent’. This, for having dared to expose the first of what was to become an endless series of official lies.

For some of us, indeed, one suspects for many millions of us across the globe, it was this event that constructed the axis of any serious attempt to place the man and his life’s work. Burchett’s biographer somehow has managed to record and acknowledge the event (almost grudgingly and selectively, in one’s own view) but to draw from it as little as possible as a guide to understanding his subject’s career and development. The traducing of Burchett was to emerge again, Kraken-like, during the course of the DLP’s trial which forms the framework of the book, when they sought unsuccessfully to tarnish him as a ‘KGB agent’.

At a second level again, then, it is one’s perception that the author has, really, failed his craft: not as a journalist because he is that, but rather as a biographer. The Exile represents an exhaustive working out of quite mammoth amounts of information (more of this later), much of which is quite absorbing and even fascinating. There are some presentations of sensitively developed assumptions which display the author’s attempts to quash the essence of this powerful and undeniably contradictory man.

But it is here that one feels rather the cold skills of the professional entomologist, picking carefully through the endless dust of detail to effect a reconstruction of a fascinating object who certainly (one is tempted to say) is ‘not really one of us’. A hint of this appears in the author’s own opening text: ‘… unlike most of his colleagues, he had never been trained on a paper …’

The architecture of The Exile goes a long way to explaining this consciously cold and removed atmosphere of examination. Willy nilly one is drawn into the adversarial mode that the author creates, using as he does the proceedings of the notorious 1974 defamation ‘trial’ of Burchett, to structure the biography. As a device lor disseminating the incredible quantity of information generated from the far comers of the world about Burchett, it serves a lot of purposes.

One area it impacts upon is the biographer’s actual style. There are throughout and regrettably, passages or pages of pure Biggies – irritating to the mind, and to the continuity of the reader’s thinking through of the matters at hand. Leaping from the Spanish Club in Sydney at Chapter 11, for example, to Rosebud in Melbourne at Chapter 12, one arrives in Peking at Chapter 13, the opening to which is quoted, as it serves as one of the shorter but representative examples:

… When Burchett arrived in Peking in the bitter cold of February 1951, it was the beginning of China's golden years before Mao’s murderous excesses which would out-do even Stalin in forced and disastrous social engineering. Peking was vivid and hopeful. The clay-walled inner city enclaves – formed a huge and colourful mosaic of ordinary Chinese endeavour. . .The only violence in the never-ending marketplace was when Moslem priests slit the throats of unsuspecting sheep …

‘Post-card politics …’ was the uncharitable thought that crossed one’s mind, while waiting for the next stage of relevance. There are many such throughout. A second, equally unkind thought followed: ‘Is this an analysis, or the preliminaries for a TV script?’ Time perhaps will tell. It certainly could be constructed into a ‘ripping yarn’ – perhaps the most ripping of which is that which receives its own special chapter headed ‘Kim of Egypt’ (Chapter 18).

In a classic use of the ‘circumstantial’ mode of journalism, and using a carefully sorted-through catalogue of incidents, the biographer imposes a mantle of inevitability upon the DLP’s hypothesis that Burchett was the KGB’s link-person who arranged the eventual flight from Egypt to Russia of the notorious UK spy Kirn Philby. This was alleged to have been done by Burchett undercover of going to Algeria for a journalistic assignment, via Cairo, at which venue he carried out the deed. Added to this circumstantial shuffling is a touch of what one calls the ‘comparative’ mode (well-known to those who have scored a page plus photo in ‘News Weekly’): Philby a journalist; Burchett a journalist; Philby worked for The Times', Burchett did as well; Philby an alcoholic; Burchett was, almost; Philby was fluent in foreign languages; so was Burchett. And so on. ‘This,’ one thought, ‘would make a smashing episode in a mini-series!’. The DLP’s hypothesis in fact, remained untested in the defamation trial, but it is a good yarn amongst the many.

There is no serious accounting in the biography of Burchett’s knowledge or background about the French former colonial empire and its dismantling. It was in fact enormously rich and relevant and an important part of his intellectual, political and professional formation. Burchett’s French connections are left in this book at the level of banalities, or occasional scraps that suit his biographer’s narrative purposes, and no more. A singular lacking of some importance, in one’s view, to the whole.

It is indeed from the way that the biographer works upon the information at his disposal that the book achieves its form: what emerges from the prodigious wealth of it all, is the extraordinary range of sources. There are with the notable lack of French language sources, seemingly endless. Wilfred Burchett’s security dossier began in April 1934 (two days before this reviewer was born!) and he was spied upon by thousands of people working for one or another branch of the secret police of at least five nations, for the whole of his adult life. One is tempted to talk of the ‘Burchell Industry’, outside of course, of his biographer!

Starting with the proto-ASIO of the quasi-fascist 30s in Australia’s official political life, through to the neo-fascist Menzies cold war years (one is told ‘… In ASIO and the military’s eyes, Burchett was political enemy number one. There was no proof of his Communist Party membership, although he was rumoured to be a secret member …’), the parade of illicit secret documentation from M.I.5, M.I.6, KGB, CIA, South Vietnam et al, is rolled out before the reader. Quite extraordinary. Out of it too, is built up a rather frightening picture: of deep hostility and genuine cold intent to ‘seek out and destroy’ this person whose capabilities were truly beyond the ken of most of his pursuers, and whose contributions were so frustrating to their own purposes.

The book recounts at great length (sometimes to a point of near confusion in one’s mind about fact and allegation) the manifest abilities of Burchett’s detractors to mobilize extraordinary resources of State power at will. These are perhaps best illustrated by one event in the defamation trial which directly involved Denis Warner, a fellow journalist who had played Cain to Burchett’s Abel over many, many years. The author tells how, mid-trial, it was possible for Warner to ring through direct from Sydney to the office of the South Vietnamese Vice President, and ‘belligerently’ demand that two defectors from the National Liberation forces be sent immediately to Australia to give evidence against Burchett in the courtroom. The duo arrived duly, within forty-eight hours!

Reference was made above to a certain clinical inhumanity that pervades the book, and one of the more-dissatisfying notes struck for this reviewer was the author’s treatment of Wilfred Burchett’s wife and partner of thirty years, mother too, of their children for whose future rights he gave up so much. Vessa Burchett is relegated to the status of a political, Stalinist hack, where not shown as vapid. Beyond what this says of the biographer’s approach to such questions (and again one finds the ring of ‘Biggies’ about it), Burchett’s relations with women form a significant dimension to the author’s purposes. Not the least is the relatively sensitive portrayal of Wilfred’s associations with Margaret, the US journalist friend. These made his dismissive observations about Vessa stand out in starker contrast, and sharpens one’s perceptions about the biographer’s art.

One was given the opportunity to meet with Vessa Burchett on several occasions, in Paris at the time of the Vietnam peace talks, and more recently in 1985 in Sofia. During along summer afternoon into evening over endless cups of tea we exchanged gossip and impressions of Australia, mostly about her family there. One does recall however, her very strong concerns that biographies about Wilfred’s complex career and its extraordinary breadth and intensity was not for the initiate, and her intentions to follow it through herself. A fascinating thought to recall now, after the help she has extended to the author of The Exile.

There is a further feeling of inhumanity too, which recurs in the book by repetition of a theme. Beyond sorting through the needs of Wilfred’s traducers to pin upon him the old tag of ‘Moscow Gold’, at any and all occasions within the circumstances of the trial, one has observed from the biographer himself a less than just approach to a fellow-journalists' finances. Not a major thing this, but one would have expected rather more sensitivity of a fellow professional, to another of his craft, than what emerges as Burchett’s constant concern with finances. As if somehow, the bringing up of a family and maintaining a home wherever one could be found in such an exacting cartel would not be a matter of moment. Perhaps the author is unattached, or has come not from the Depression years, and has been better at east in his circumstances.

A final assessment of Burchett is offered in what for this reviewer was a not very tasteful, rather jumbled last few pages of the book. Burchett’s life is collapsed into a two line sentence: ‘Burchett did open up against the Nazis, Fascist Japan, the atomic bomb and US mistakes in S.E. Asia’. And judgement follows equally swiftly, ‘but his price for the privileged observation of a great deal more iniquities of history was silence’.

In effect his biographer charges Wilfred with having been paid to be silent – on Stalinist shows trials, Czechoslovakia in 1968, the Red Guard purges, Afghanistan in 1979, and a host of other events; most notably the Pol Pot period in Kampuchea. Silenced with hush money in his biographer’s eyes meant consent. And yet in a strange volte face he also suggests that had Wilfred spoken out on any or all of these events he could or would have been assassinated (the CIA is reported to have considered this, the Khmer Rouge certainly tried)! One is left with the nasty feeling that Burchett was not only bought, but that he was, perhaps, a coward?

The Exile represents for this reviewer neither a satisfactory nor satisfying summation of the man and his contributions. It may well be a good script for a mini-series, entertain a lot of Australians and make a lot of money for someone. It will also reaffirm that amalgam of prejudice and establishment values that it was Burchett’s life work to challenge to the limit. As a serious study the biography diminishes its subject and as a reader and a fellow Australia, to boot, one also feels diminished.

Comments powered by CComment