- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Andrea Goldsmith’s second novel, Modern Interiors, is about a family, and marked out by its goodies and baddies. This is a moral novel about capitalism and the choices open to people within its system. Goldsmith uses outrageous caricatures to represent the baddies – those seduced and corrupted by the family’s damned money. And all of the goodies have an interest in and strenuously pursue the higher knowledges – poetry and fiction, philosophy and philanthropy. They are all good, and fair-minded people, if sometimes with too much sweetness and light.

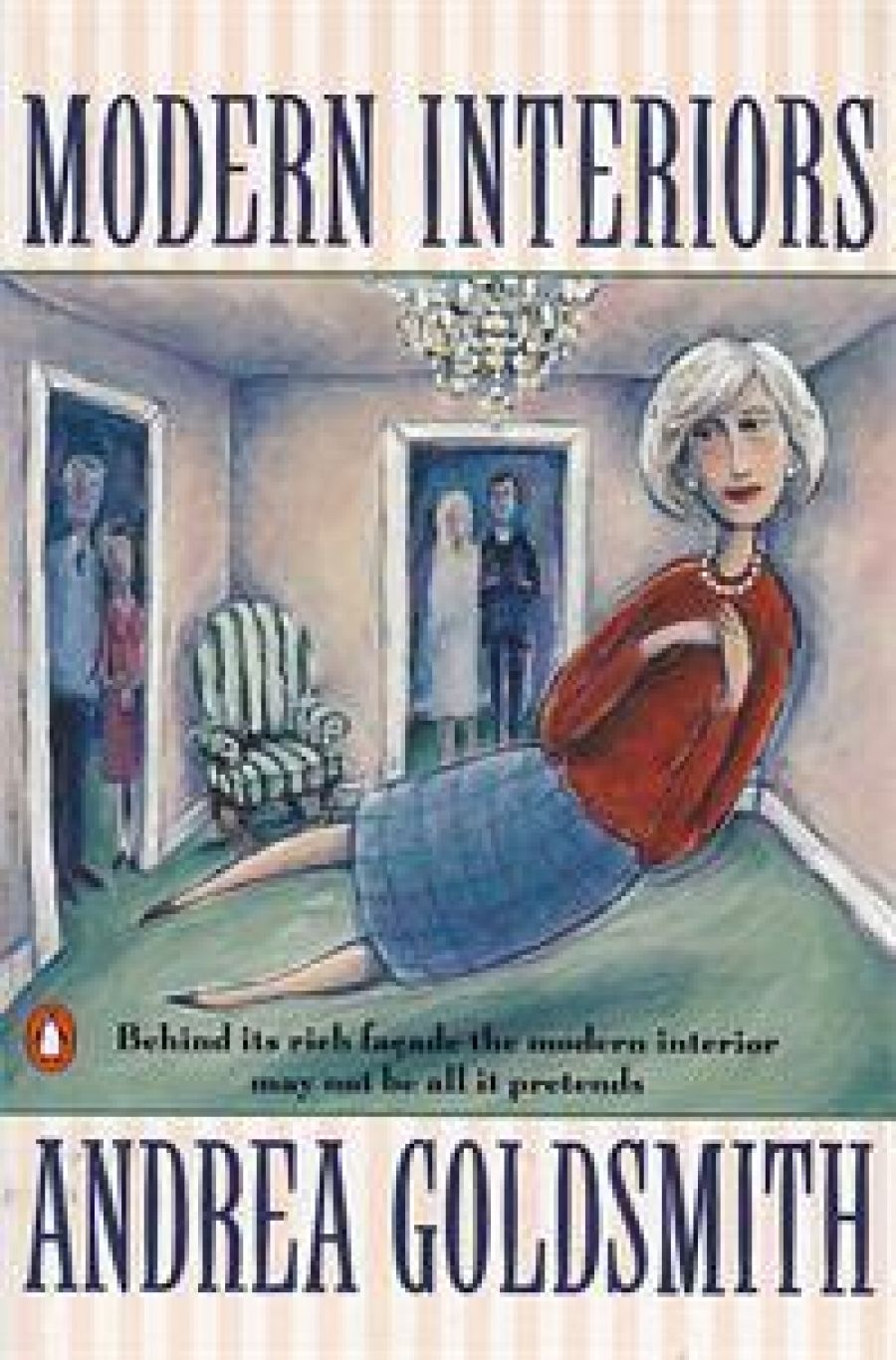

- Book 1 Title: Modern Interiors

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin, 242 pp, $14.95 pb

The novel starts wonderfully:

After a meal of rare roast beef, potatoes au gratin and green beans, George Finemore poured himself a scotch, settled in front of the television and died. A premature death on a wet June night – although tidy enough, the doctor said, diagnosing a massive and efficient stroke.

Straight to the point. But as we begin to learn about the Finemore family, we get a lot of repetition. Goldsmith’s dilemma, I suppose, is how to develop a few of her characters who are crashing bores, lacking any imagination, locked into living their lives as clichés, and who are determined to maintain snobbish existences in an ‘established’ family. There is an attempt to describe how an upper-class family constructs itself: two of the three Finemore children and their spouses have a fixed idea of what it is to be born into this family, what is expected, and what they can expect to get, and they will not allow for change. They are fiercely critical of their mother, the remaining head of the family, because of her idiosyncrasies. They are particularly critical of her need for change, especially when the opportunity is offered to her by the premature death of her husband. All the baddie characters seem to think only of themselves and what their social standing means: ‘What Melanie meant, but considered it in poor taste to say, was that wealth brings responsibilities, wealth sets one apart, and there could be no doubt that Philippa was very well off.’

And so, the main character of Modern Interiors is Philippa Finemore, a woman who explores her own potential for almost the first time as a sixty-three-year-old widow, a very wealthy widow. The threads of the novel involve and explore the things that get in her way, which are mostly her children and their spouses – a collection of greedy, weak-willed, and ultimately selfish creeps. The only child she has any sympathy with is Jeremy, an outcast from the family proper, not only because he is a homosexual but also because he is an intellectual, or at least an academic. But Jeremy is prepared to support his mother through any transition she may choose. While the pace tends to be quite tedious at the start of the novel, it finds some focus as we go through each of the children’s responses to Philippa’s changes, when she starts to find her feet in her new world and new characters are introduced. Some lovely relationships are developed. The connection with the waif Amy is a chance for Philippa to escape her own class for a change, to engage with other sorts of issues, to free up a bit beyond her world of moneyed society and the merchant class. Her relationship with Amy offers her much; as a surrogate daughter she offers Philippa more than was on offer from her own daughter. And, as well, the introduction of her lover, Leo, a Jewish leftist bookseller, in fairly obvious ways loosens up parts of her life.

The best part of this tale is that the goodies win out and the baddies get their comeuppance. Philippa manages to restore an integrity to the family company, Finemore Fine Wines and Spirits, by kicking out the boys and investing her husband’s long-term mistress, the shrewd and good Lorraine, as boss. But the basic problem with the novel is that Goldsmith introduces too many threads – the grievances of the characters, social questions, black humour – and all of this just swamps the story.

And so much of it reads as gratuitous and silly. I think that it is just that Goldsmith has not decided clearly enough what sort of book she is writing, so nothing is really worked through strongly enough. My final quote is a good example of why I am concerned, since it shows how too many ‘hooks’ are grabbed, bunched together to give us a sense of modern life:

Then, on her return, she had resigned her voluntary work at the nursing home (too close for comfort, she said), taken up yoga and joined Friends of the Earth. The Mercedes had developed a farrago of stickers advertising her new interests: ONE NUCLEAR BOMB CAN SPOIL YOUR DAY, THE AMAZON FORESTS ARE THE WOMB OF THE EARTH and, worst of all, SAVE A GAY WHALE FOR CHRIST.

‘You can’t have that on your car!’ Melanie protested.

‘Be sensible,’ Gray pleaded.

Only Jeremy, the second son and middle child, approved, and not merely of the gay whales but of his mother’s whole new orientation.

Comments powered by CComment