- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Figuratively speaking Shark reminds me of a pencil-and-paper game: change FOX into SHARK a letter at a time, so that the stepping-stones of words like the one to the other. For Fox is back, back from the independence struggle in West Papua and retired to Australia and the evocatively named coastal town of Tired Sailor, and by the end of the book Fox has become Shark, elegiacally linked by some of Bruce Pascoe’s most lyrical prose.

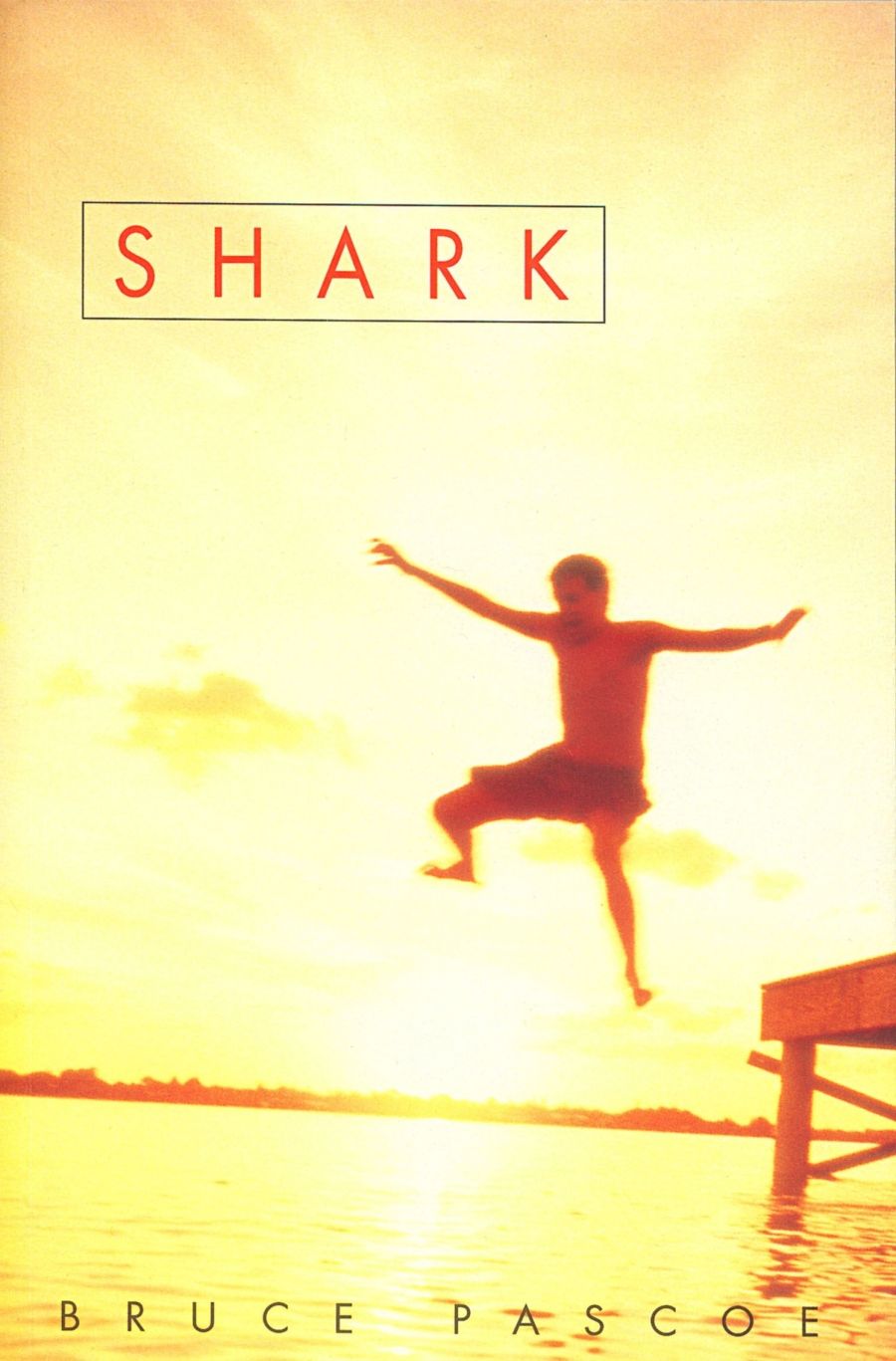

- Book 1 Title: Shark

- Book 1 Biblio: Magabala $16.95pb, 216 pp

Pascoe introduced Fox in the novel of the same name – Pascoe’s first – in 1988 where the ostensibly white Fox uncovered the Aboriginal in his roots and went in to bat for equality and land rights. Ruby Eyed Coucal (1996) took him to lrian Jaya and drew out the parallels in dispossession between West Papuans and Indigenous Australians. It also gave Fox a full grown daughter, Maree Fox McConnell, who became involved in an action to counter the claims of Terra Nullius on the basis of the international trade Indigenous Australia had carried on, for generations before colonisation, with the Macassans, Papuans, and Chinese.

Ruby Eyed Coucal ended with the birth of Maree’s son, Fox’s grandson, a birth recounted in messianic terms, but Reuben – part Aboriginal, part Thursday Islander, part white – if he is to be a messiah, is biding his time in this book, growing from toddler to teenager under the undemanding tutorship of Tired Sailor, discerning his destiny, and becoming acquainted with those who share it. In terms of the contemporary epic he has embarked upon, Pascoe, too, can be seen as marking time, perhaps waiting for history to catch up with his fiction: for the effect of events in East Timor to impact on West Papua, for the national interest to turn from taxation back to the stalled processes of reconciliation and land rights legislation.

This is a book of baton changes, as the old, tired, and patient hand over to the more volatile, more highly educated, and more intransigent young. With a sense of shock and loss the reader is forced to farewell old friends and introduced to new ones, to the more idiosyncratic citizens of Tired Sailor, particularly Emily Frazer and Rooster Clark, who are drawn with all Pascoe’s flair for the apt and often essentially Australian image. Thus the body of Emily the lovelorn spinster bait-pumper is described as ‘flat, hard and and blondly furred as of those Oregon planks that get washed up after months of salt and sun exposure and abrasion of rock and sand’, and her conjunctions with Fox as the stilt-legged dance of brolgas, while scrawny, black, unshaven old Rooster has ‘the appearance of an aggressive echidna’ and is ‘as romantic as the hard end of a clump of celery’.

Pascoe is trenchant colloquial and often satirically funny, lampooning bored bureaucrats and pushy radio presenters with malicious verve. He has combined a rallying call to reconciliation with adventure, racial politics, and romance, and done it generally with a balance and restraint that were missing from Ruby Eyed Coucal. After the frenetic activity of that novel the dominant mood of this one is elegiac. There is much to mourn: death, disillusion, the apathy of self-interested government and, particularly, loss, whether it is the loss of a loved one, the loss of connection to land and language that Rooster comes to feel so desperately, the loss of innocence suffered by Reuben and Rooster’s son Rocky as they experience for the first time the antipathy of the wider world, or the loss of an opportunity for Australians at last to build a nation based on truth.

There is also, however, a positive and practical sense of mourning and moving on, often enhanced by memorable imagery. Rooster takes Reuben to watch the sharks dreaming deep in a swift ocean current, allaying the boy’s grief and his own fear with their tranquillity. Emily confronts Rooster with the haunting evidence of family atrocities, and seals their reconciliation with the gift of the clinker, ‘a craft whose timbers are bent under pressure, heat and steam and caulked and lapped together to give them strength. The bonding lasts if not abused and taken for granted.’ Rocky’s stint in jail arms him with the determination to bond White law with Koori ways.

When the book ends, it is with the promise of a beginning: Rocky and Reuben are poised to take on their messianic roles, Rocky to challenge Australia to a new constitution, Reuben, as the reincarnation of Fox, to rejuvenate the West Papuan independence struggle. But who knows when that novel will be ripe for writing? In an editorial aside Pascoe exclaims: ‘Patience friend, keep reading your newspapers, watch your screens, Rocky will introduce himself shortly ... What’s a novel anyway but a poor man’s guess at the future ... ’. Perhaps the next novel depends as much upon us, the citizens, voters, employers of Australia, as it does on Rocky Clark or, indeed, Bruce Pascoe.

Comments powered by CComment