- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

It’s interesting how many comic autobiographers are theatrical, like Barry Humphries, Clive James, Hal Porter, and Robin Eakin, whose Aunts up the Cross (1965) is a minor masterpiece and very funny. Eakin’s belated follow-up, An Incidental Memoir, published under her married name of Dalton, compares interestingly with Dulcie Deamer’s posthumously published The Queen of Bohemia.

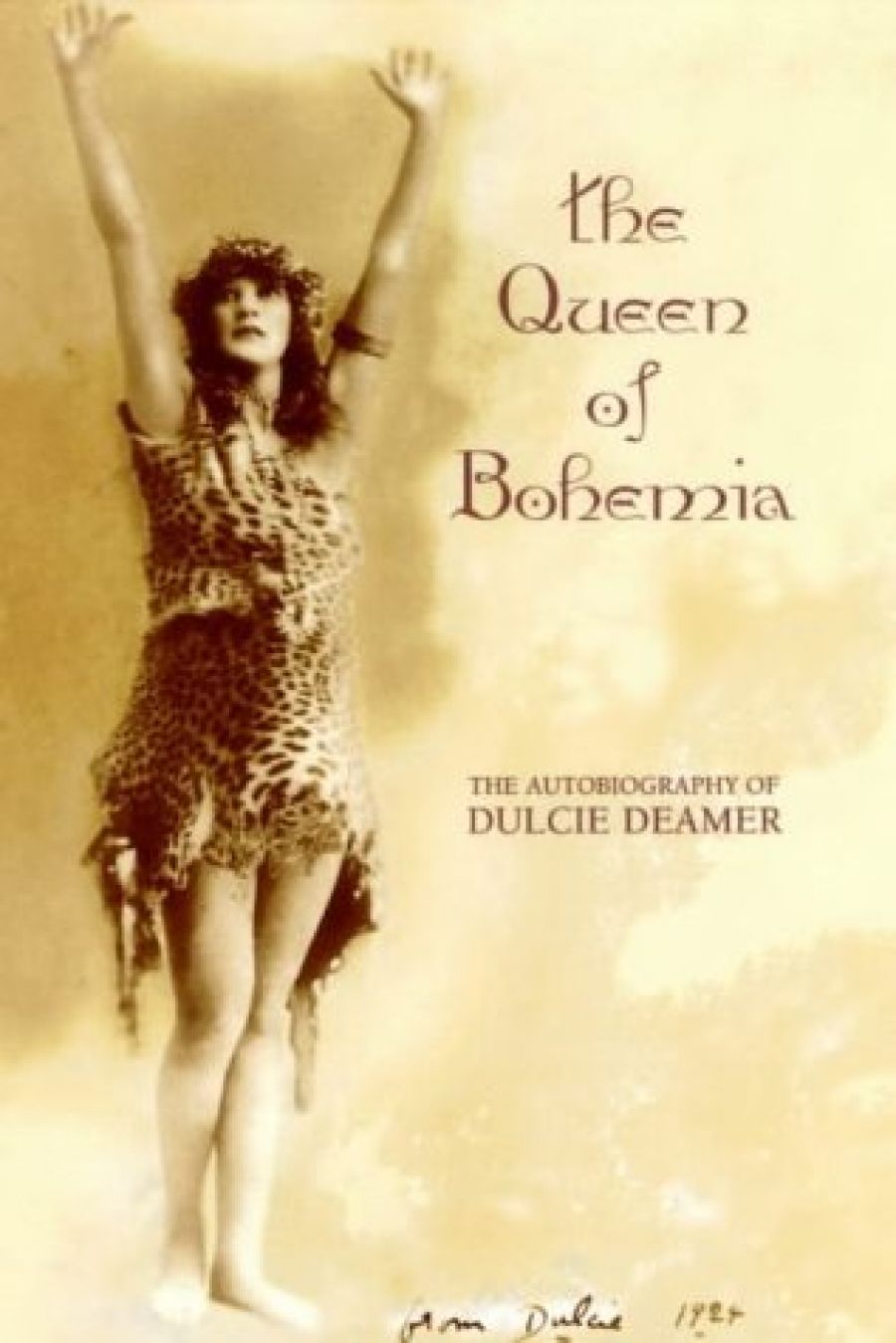

- Book 1 Title: The Queen of Bohemia

- Book 1 Subtitle: The autobiography of Dulcie Deamer

- Book 1 Biblio: UQP $29.95 pb, 239 pp

- Book 2 Title: An Incidental Memoir

- Book 2 Biblio: Viking, $29.95 hb, 368 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/ABR_Digitising_2021/Apr_2021/An Incidental Memoir.jpg

By her death in 1972 Deamer had become a personification of the swinging bohemian days of 1920s Sydney. Like many famous Australians, Deamer was born in New Zealand. In The Queen of Bohemia Deamer affects indifference to her early life, telling the reader to skip the long ‘Personal Prologue’ if interested in her bohemian tales. But this section is most like what we expect of an autobiography, and it’s not surprising that readers of the unpublished manuscript thought it the better part of the book. Deamer’s account of childhood is refreshingly matter of fact: killing rats and then giving them a funeral and tombstone (her father – more endearingly – liked warming the cats’ cushions by the fire); experiencing early twentieth-century paganism by feeling a ‘Presence’ in a Wellington garden; and having a liking for nude sun-bathing. She emerged from obscurity by winning a story competition at the age of seventeen with a tale set in the stone age. Soon after, she married Albert Goldie, a feckless journalist, whom she eventually discarded for the delights of Sydney, a lifetime of freelance journalism, and the bohemian camaraderie of ‘the Noble Order of I Felici, Letterati, Conoscenti e Lunatici’.

Before that, though, Deamer’s literary prize brought her sufficient fame for her to join a pioneering repertory company which is presented as simultaneously seedy and morally upstanding. Moral conservatism is also central to her account of bohemian Sydney, and Deamer is keen to refute Jack Lindsay’s alcohol-soaked picture in The Roaring Twenties (1960), presenting instead a playful, theatrical, and innocent picture: ‘everybody played’, she writes.

The text is illuminated through notes by Peter Kirkpatrick, whose extensive knowledge of bohemian Sydney is also seen in The Sea Coast of Bohemia (in which Deamer figures largely). Kirkpatrick gives amusingly straight-faced synopses of Deamer’s impossibly dated fiction, and many concise, but telling biographical entries on the heterodox of Sydney, like John Norton, the rowdy parliamentarian, once ejected for urinating in the House of Representatives.

When it comes to autobiography the Upper House can block bills, but not say why. Certainly, Deamer presents many significant gaps, such as her breakdowns, and her children whom she left with her mother. Her account of Sydney is less compelling than the ‘Personal Prologue’, perhaps because it is so resolutely cheerful, and therefore a little unconvincing. Nevertheless, she gives many interesting vignettes of figures such as Christopher Brennan, David McKee Wright, and the extraordinary Mrs Lala Fisher. Such cultural history is the work’s raison d’être, and we should be pleased that Deamer’s autobiography has been published in so sympathetic a way.

One wonders what Deamer and Dalton would have made of each other. Their histrionic flair would no doubt have smoothed things along. But Dalton’s milieu, while artistic and theatrical, is utterly different from Deamer’s. Dalton, who left Australia for London just after the War, came from – and largely remained in – a world of privilege and good connections, and of savoir faire in the face of royalty, or primitive living conditions in Italian towers, or the boundless unreliability of movie financiers. Dalton begins with a ‘society’ divorce; becomes engaged to a Marquis (who was to be Prince Philip’s best man); hangs out with European royalty and a youthful JFK; becomes a spy for the Thai government; is widowed with two small children, and becomes a literary agent, with a late career as a film producer.

Affecting a lack of interest in name dropping, Dalton drops names thick and fast. ‘I met the Windsors only twice,’ she writes, referring to the Duke and Duchess. Dalton presents her younger self as brash, pleasure-seeking, and innocent. Interestingly, both she and Deamer present their lifestyles in terms of innocence: as a joie de vivre, a ‘divine frivolity’. Dalton even says of her spy boss that the subsequent discovery of his involvement in organized crime ‘still emerges from the memory of his benign despotism as a sort of innocence’. It is very easy to feel like a Marxist when reading this book.

But Dalton is not just one of those superannuated bright young things who turns out quite dull. Her sense of humour, and genius for comic anecdotes is too pronounced for that. One can see many of the features that make Aunts up the Cross such a memorable book. But one key feature, brevity, is conspicuously absent. Being the soul of wit after all, brevity is the missing deity of this work, which is woefully under-edited. Dalton’s apparent desire to include almost every anecdote of her repertoire may have been bearable if an editor had seen to the excessive detail: of a minor hurt occasioned by Hal Porter, or the absurdly large set-up for a small joke about a litigious agent, or the minutiae of raising finance for a film. Such things make the work painfully copious.

This is a shame, because the book despite its faults, is admirable. As well as the intriguing insight into post-war London for the fabulous and fabulously wealthy, Dalton writes affectingly about raising her children as a young widow. And there is real pathos in the account of her second husband’s death. And interestingly, despite the discontinuities of her life – which seem quite pronounced – Dalton seems untroubled by a fragile or discontinuous sense of self. Perhaps this is because of the continuity of style, visible in her books, despite the gap of half a lifetime.

As a literary agent and film producer, Dalton has been well placed to see the destructive, as well as supportive, effects of the histrionic life. Perhaps coincidentally, the three films she has produced arc concerned with this theme. The best of them, the shamefully under-appreciated Country Life, has most to say about this. But Dalton has little to say about the meaning of the films she produced. Like Deamer, her autobiography attests not only to the theatricality of comic autobiography, but also to the engaging plangency of an autobiographer playing for laughs, especially one old enough to know better.

Comments powered by CComment