- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Letter collection

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The status of Henry Handel Richardson as a writer in Australia has always been somewhat problematic. Some people put that down to the fact that she was an expatriate. Leaving Australia at the age of eighteen, she returned only once, very briefly, in 1912. Expatriates, however, have often been paranoid about their reputation in this country and inclined to imagine that the Australian public is punishing them for leaving whereas in most cases it is indifferent to or even ignorant of that fact.

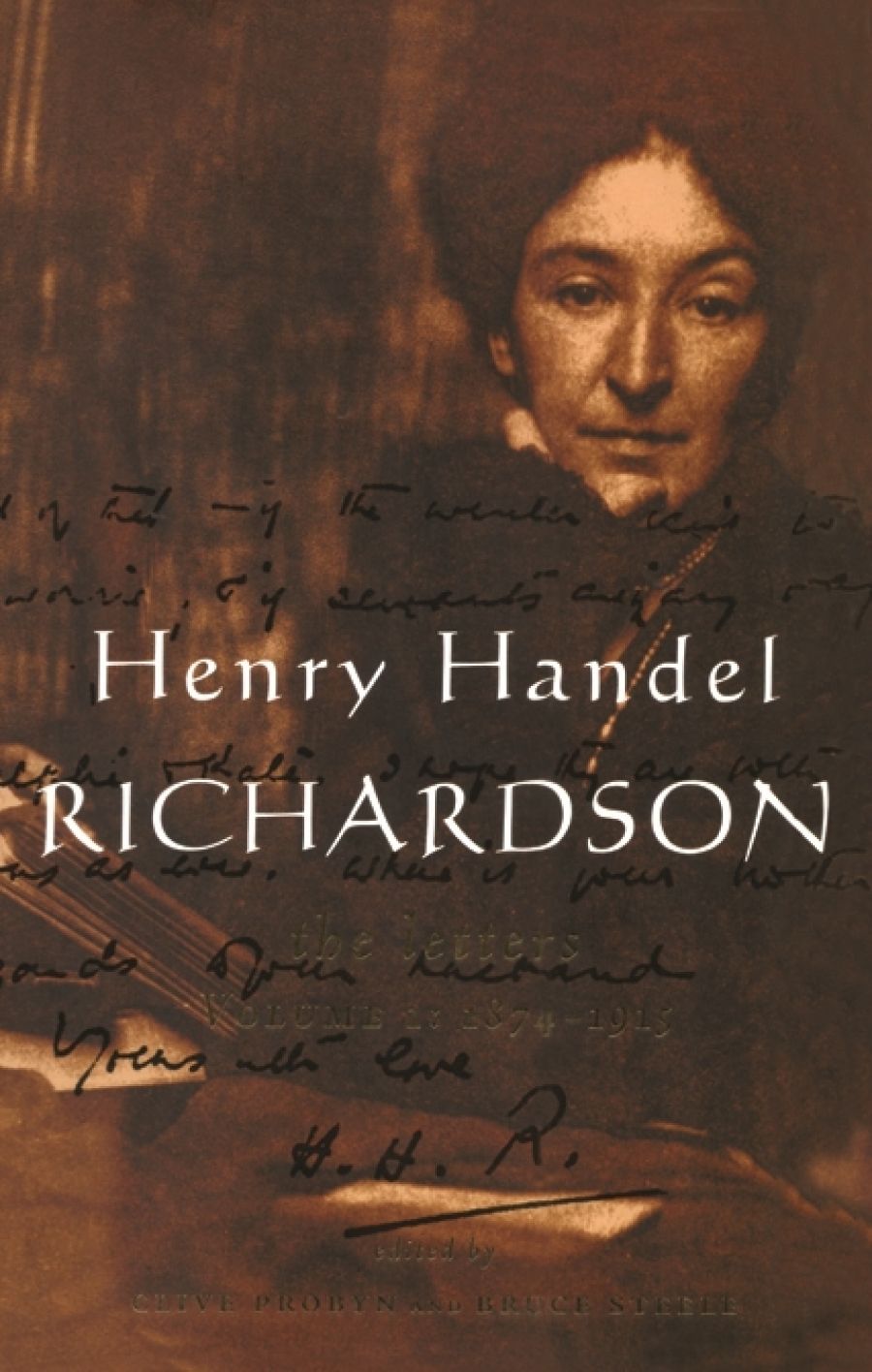

- Book 1 Title: Henry Handel Richardson

- Book 1 Subtitle: The letters

- Book 1 Biblio: Miegunyah Press, $88 hb, 660 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/9WWVb0

I have always thought that she was one of our most powerful fiction writers, one of the finest in a great Australian tradition of secular and sceptical writers that begins with Marcus Clarke and goes through Furphy, Richardson, Xavier Herbert, and Christina Stead. (The conspicuous exception, of course, is Patrick White.) The Getting of Wisdom is a wonderful novel, the best of all the numerous Australian rites of passage novels. The foundation of her achievement is The Fortunes of Richard Mahony, which simply gets better each time one rereads it, while there are several remarkable stories. Maurice Guest has many powerful scenes, though it is limited perhaps by its melodramatic genre, while The Young Cosima shows a definite decline.

This edition, say the editors, increases the total of Richardson’s published letters from forty-five or so to almost one thousand. They are published in two volumes with a third one promised shortly. Most of the letters in Volume One are to or from Paul Solange, who was doing a translation into French of Maurice Guest. It is a meticulous, ordered correspondence on Richardson’s part. Solange constantly berates himself for taking up so much of the author’s time with his questions, but then sends another letter to which Richardson replies in comprehensive detail.

However, the correspondence between them is less than riveting. I wonder if it were really necessary to print the translations of Solange’s part of the correspondence as well as the originals. This is especially the case, given that the translation was never completed: the indefatigable Solange died suddenly of pneumonia with just three chapters left unrevised.

We don’t learn a great deal about Richardson from these exchanges except for the odd delight she took in keeping her gender secret from her correspondent, who constantly begs her for a meeting or at least a photograph. Richardson eventually has her delicious revenge when, commenting on the House of Commons defeat of women’s franchise in 1912, Solange (who most of the time is quite reasonable) quotes Dumas fils’ remark that ‘Woman is an illogical, subordinate and maleficent being’ and goes on to say, ‘That’s in her normal state. My God! what is she when she is controlled by the need to vote? I am sure there are not three pretty women among your suffragettes.’ In reply, Richardson calmly says that ‘Of course, I am a feminist’, without revealing that she is also a woman.

She is very interesting when she defends Maurice Guest from H.G. Wells’s criticisms. She describes herself accurately in response to Solange’s concern that she is becoming discouraged:

If discouragement there be, it is a such a deep-seated, integral part of me, that I have no earthly control over it; (it) is what the Germans would call a ‘seelische Verstimmung’. It is born, no doubt, of a very pessimistic outlook on life, & a deathly weariness of things in general that sometimes takes possession of me; but it goes hand in hand with a vigorous hold on existence, & with the unyielding toughness of the born fighter.

Did anyone ever know herself better?

The letters in Volume two are more varied. Many of them are of little interest; most letters not deliberately written with publication in mind tend by their nature to be fairly boring and usually deal with practical and often trivial detail. Nevertheless, Richardson occasionally makes interesting remarks about her methods and habits. The letters cover the period of publication of Ultima Thule which, after a quarter of a century of writing in relative obscurity, finally made her a success.

One of the surprising things about the letters is Richardson’s caustic view of England. It confirms my view that Richard Mahony is by no means the declaration of the superiority of English values over Australian that it was read as in the fifties. She is continually critical of England and at one point says brutally, ‘I think it is a country made chiefly to get out of: I dislike its climate, its people, its politics, and its want of feeling for art. If I could have my way, I should never spend more than three months of the year in it.’

Another revelation of the letters (to me at least) and tribute to her heroism is the extraordinary degree to which she was afflicted with illness. Few letters go by before there is mention of yet another debilitating affliction – nephritis, influenza, rheumatism, conjunctivitis, bronchitis. That she could write at all is amazing. As for the accounts of contemporary Australia, a friend writes to her that ‘We are all sport, money & pushing activity. Little literary papers are started & run about a year & die unnoticed deaths.’ Plus ҫa change ...

This is an important collection of letters, edited with great thoroughness, and produced to Melbourne University Press’s habitual standard of excellence. It will be of enormous value to scholars and libraries.

Comments powered by CComment