- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

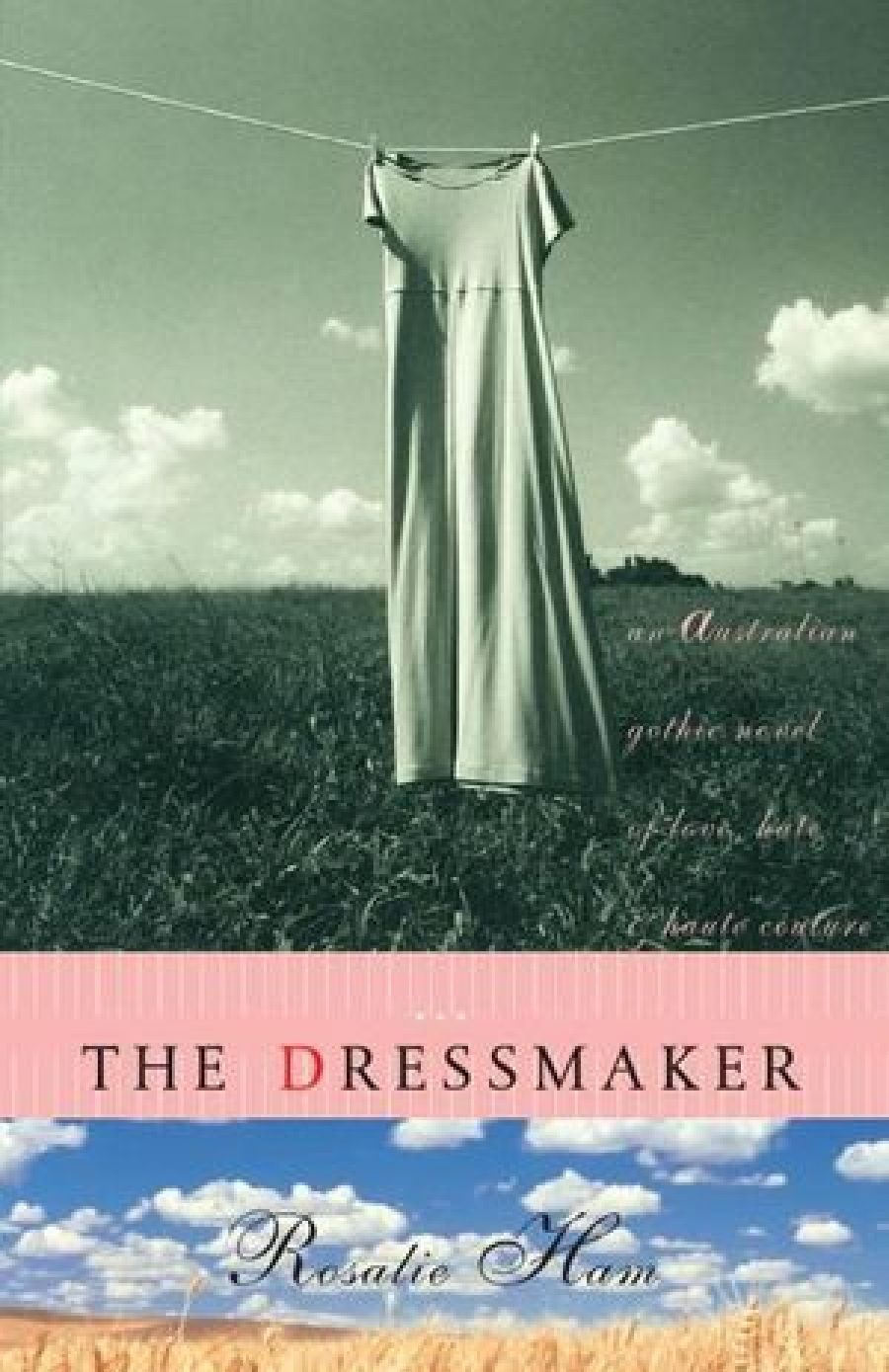

Set in the 1950s in a tiny Australian country town called Dungatar, Rosalie Ham’s The Dressmaker explores the rippling effects of chaos when a woman returns home after twenty years of exile in Europe. Tilly Dunnage was expelled from Australia in a fog of hate and recrimination; her neighbours have never forgiven her for an act Tilly thought was predicated upon self-preservation, but others chose to see as manslaughter. Returning to look after her senile mother, Tilly sits in a ramshackle house atop a hill while the town people below bitch and snipe at her with rancorous glee. This is a story about loose lips and herd mentality bullying in a town where everybody knows your past. The dressmaking title refers to Tilly’s fabulous seamstress skills (she learnt the trade overseas). But even her ability to transform the frumpiest shapes into figures of grace does not mellow the unforgiving hearts of her neighbours.

- Book 1 Title: The Dressmaker

- Book 1 Biblio: Duffy & Snellgrove, $18.95 pb, 296 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/WB9e3

- Book 2 Title: Black Hearts

- Book 2 Biblio: Random House, $18.60 pb, 400 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/1_SocialMedia/2021/Jan_2021/7945951.jpg

Ham’s first novel suffers from a number of serious faults including rampant stereotyping and narrative thinness. But most damning of all, it is simply boring to read. Part of the problem is that Tilly has too many neighbours; it seems that the entire population of Dungatar has been allocated space in the narrative. This long roll call of eccentrics simply negates any chance of in-depth personality analysis. There’s only room in the book for one or two defining traits of each resident and they’re all woefully stereotypical. So we have Beula Harridene, the nasty gossip, Evan Pettyman, the sleazy shire president, Purl Bundle the lusty, busty short-skirted publican’s wife, Mr Almanac the dotty pharmacist and so on and so forth. These caricatures are hazily sketched, ugly country bumpkin tropes against which Tilly is shown in sharp relief – behold the beautiful European-schooled sophisticate. But even Tilly herself is an enigma. Little by little her sad history is revealed (to wit, why she left Dungatar and why she returned) but we’re never allowed under her skin and in the end, she is no more sympathetic or engaging than any of the other characters.

It comes as little surprise that everyone in this claustrophobic town nurses’ secrets. The litany of indiscretions ranges from prolific infidelity to cross-dressing. I thought at one stage that Ham was indulging in a perverse version of Stella Gibbons’s Cold Comfort Farm. In both books the secrets hiding in the woodshed threaten to wreak merry havoc on the rural population, but Ham’s farce has a far blacker tinge. Gibbon’s heroine confronts a family in disarray and manages to magic wand everything into happy endings. Meanwhile, in The Dressmaker, Tilly confronts her ugly and charmless neighbours and tries to sweeten their venom with the allure of haute couture but ultimately realises that gorgeous clothes cannot hide horrible natures. Her ultimate revenge against the town is melodramatic and seriously misjudged.

Ham tries hard to lighten the banality of Dungatar by depicting quaint, hokey ‘country life’ activities. Thus, we have descriptions of footy games, fund-raising afternoons of tea and croquet, dances and amateur theatre productions. These are all mere window-dressing to disguise the insubstantial narrative because despite the usual hyperventilating blurb, Ham’s debut has nothing new or interesting to say.

Like The Dressmaker, there is a preoccupation with the past and its stranglehold on the present in Arlene J. Chai’s fourth novel, Black Hearts. Chai’ s protagonist, Christina Hidalgo, is also forced to return home after a long absence away. After her grandmother’s death, Christina is left in possession of the family mansion, Casa Aragon. Reluctantly she accepts responsibility for it, if only to use it as a weapon against her estranged sister Serena. Ham’s Tilly may well indeed agree with Christina as she reflects, ‘Gazing upon my unexpected inheritance I felt the crushing weight of this simple truth: all our journeys lead us home, there is no escape.’ Her grandmother’s malevolent presence still haunts the house; Constancia Aragon had collected people as she collected objets d’art and her granddaughters were jealously guarded possessions. As Christina and Serena struggle to free themselves from their grandmother’s clasp, power games of manipulation and revenge follow.

Chai says in her acknowledgments that Black Hearts was more difficult to write than any of her previous novels. It’s an interesting admission because it seems that the prose in this latest offering is more stilted and affected than her previous works. While The Last Time I Saw Mother, Eating Fire and Drinking Water and On the Goddess Rock dealt variously with identity and familial connections, they were also expansive in their treatment of history and politics. In Black Hearts, the world has contracted to the spaces of a gloomy house.

Though set in the present time the novel has a curiously old-fashioned air. At once passionate and sombre, Black Hearts can simply be read as a romantic thriller. Certainly, Chai provides the requisite ingredients: a dastardly matriarch, orphaned sisters, a grand Gothic house, mirrors reflecting shame and exaggerated enunciations about the nature of evil. For instance, ‘Look, look into the heart of Constancia Aragon. It is black. So black that I am sure the heavens brightened the day she descended to hell. May she burn.’ For me Black Hearts is more fairy-tale than real-life verisimilitude. The garish characters, cavernous estate and overwrought narrative all conspire to suggest a brother’s Grimm tale. Chai herself makes reference to princesses being locked up and awaiting rescue. There is even a pair of beautiful, diamond-buckled shoes. But this is no Cinderella tale, or rather this Cinderella doesn’t get her prince and, in the end, thinks she is just as ‘evil’ as her sister and her grandmother. (The word ‘evil’ is thrown around a bit too carelessly.) If you want escapist fiction Black Hearts is a competent albeit formulaic, paint-by-numbers distraction.

Comments powered by CComment