- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: And when did you last see a giant?

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

While she was writing her novel, Angela Malone pinned a panorama photo of Hill End, the small NSW goldmining town, over the window near her desk. The photo seemed empty of life until Malone took to it with a magnifying glass and – as authors do – playing the giant game, discovered shadowy traces of some of her characters. No wonder, since the town lies on a bed of quartz which common wisdom invests with certain powers of invocation, much like the magic of the silver particles of photography. Hill End became the novel’s Reedy Creek, a place infinitely embroidered with the history and folklore of its predominantly Irish community.

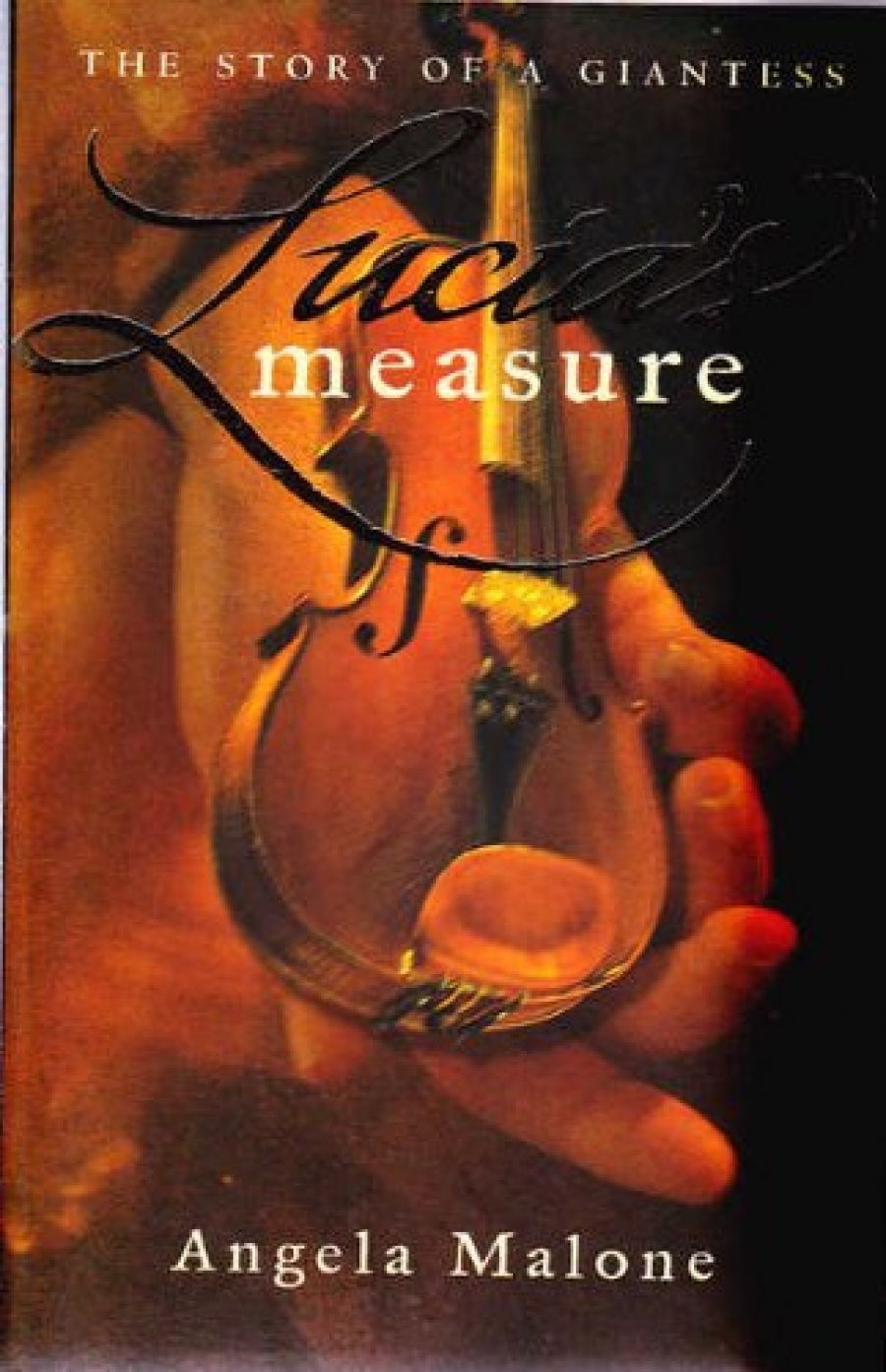

- Book 1 Title: Lucia’s Measure

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Story of a Giantess

- Book 1 Biblio: Vintage, $17.95, 197 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Earthbound readers may be a little dislodged from the very beginning, while those who enjoy a bit of literary topsy turvy will feel right at home, sparked by the melodrama of monstrous graves, mad priests, big girls, a town’s population of short men all wishing to be taller, and an old woman’s shotgun mysteriously pointed at an oversized overcoat. Significant characters have butterfly birthmarks and wear shoes with butterfly buckles. Where would Magic Realism be without butterflies?

The strangeness never eases up, as we join in a rollercoaster search for lost pieces of the old woman’s world – she is called Mts Bridy – including bits of herself (wink, nudge) ‘she hadn’t even lost yet’. The reasons for this quest remain part of the story’s enigma. Clues wind between the present and past, reality and fantasy, as intricately braided as ancient illuminated Celtic whorls. The language is often similarly elaborately wrought, sinuous with double negatives such as ‘there was a time when … you would never have noticed’ and an incantation of ‘I don’t know how’, ‘I cannot remember’, ‘I didn’t know why’, peppered with ‘as ifs’ and ‘could have beens’, with guessing, imagining, and dreaming. The imagery also intensifies an atmosphere where the paranormal is normal, where everything is invested with either shadowy or blissful significance, where winds blow with ‘the sweet breath of the undertaker’s daughter’, and characters fall ‘into the dug out pits of one another’s terror.’ A rather sentimental, talking river, with the power to drown people when it floods, is allowed to boast that ‘there was a time when no-one knew how deep I was.’

Through a crowd of Reedy Creek folk – blind men who are visionaries, hairless barbers, Sergeant Finnigan, Delores Hawkin, Seamus Tully, the Nettle Sisters, Florrie O’Dowd, the names trickle off the page like mead – each of whom harbours pieces of the old woman’s narrative, and past garlands of chicken wishbones, nests woven from horse’s hair, 122 pairs of woolen tights, 1,000 fans, encountering such dizzying detail that it is hard to know if it is evidential or misleading, one twelve-year-old Kitty Charlotte O’Reilly, of whom it might be said that she is tall for her age and growing, orientates us towards pine-chilling screams, sighs, whisperings and innuendo, and into the centre of things, an eerie domain called Petticoat Flat – pun intended, I’m sure – where netherworld love-bargains are struck between an undersized musical pumpkin farmer called George Clancy Tynan (Kitty’s grandfather) and a beauty called Lucia peddler, who is – as beauties often are – larger than life. The sum of it is that he trades the secrets of his heart – and thereby hangs many another diversionary tale – for her extraordinary inches. He grows and she shrinks. Not an unfamiliar consequence of romantic attachments, some readers might chuff.

The curious thing is that it is all communicated, breathlessly, as in a traditional storytelling competition at an Irish village festival, with only the merest hint of authorial attitude, three parts performance to one-part literary consciousness. To choose the closest comparisons that come to mind, there is in this novel no irony, as Carmel Bird would have had it, no undercutting and cross-slashing, in the manner of Angela Carter, and none of the sexual menace one finds in the work of Barbara Hanrahan. More naively, Malone’s characters are burdened only by their almost suffocating accumulation of in interlocked secrets, bursting with tales, which makes them charmingly or annoyingly old-fashioned.

Malone says, ‘growing up my father mythologised our home and the bush in an Irish way.’ Except for the occasional reference to a currawong, a wallaby or a stringybark tree, however, the sense of place is more Ireland – or Ireland grafted by the imagination – than Australia. If the act of mythologizing is a migrant’s mode of being in the world, a type of human behaviour that is central to traditional societies which are becoming more fragmented, displaced, and revised, the fabric of mythmaking – the cutting and sewing and yarn spinning of Lucia’s Measure – lives on as individual experience, at once monstrous and enchanting.

Comments powered by CComment