- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

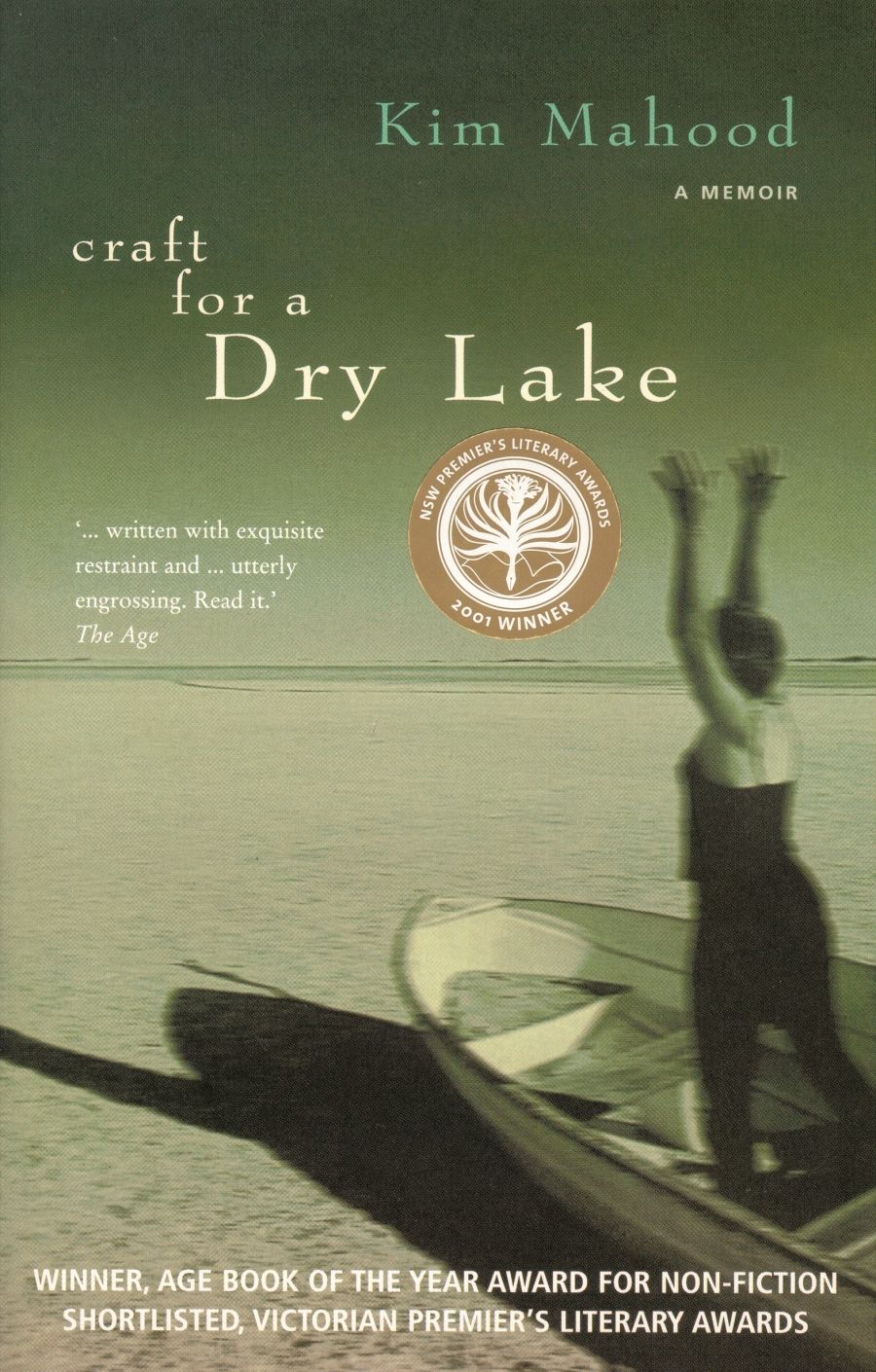

‘We had always been close’ is the first sentence of Kim Mahood’s beautifully crafted memoir. She is speaking of her father who was killed in a helicopter crash while mustering cattle on his remote Queensland property. Craft for a Dry Lake is about the journey she made through the outback country of her childhood following his death.

- Book 1 Title: Craft for a Dry Lake

- Book 1 Biblio: Anchor, $22.40 pb, 266 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/x99JBy

Alexander (known also as Alec or Joe) Mahood’s death came at a time when his daughter, an artist, was preparing for an exhibition:

I finally felt I had pulled free of my father’s influence … the work was to be a declaration to myself of the legitimacy of my own vision … betraying some old and precious agreement … he would finally know I was not the daughter he adored, but a stranger whom he neither knew nor understood …

Joe Mahood had also wanted to be an artist. It was with his pencils and sable brushes Mahood made her first impressions on his canvases – not always to his delight.

Craft for a Dry Lake is a complex narrative. The narrator’s voice and point of view continually changes from first to third, back to second, then first again and so on. There is the voice of the young Kim which is related in third person giving a distancing effect, eliciting a truth in her observations without cloying sentimentality. Then there is the voice of Joe Mahood through excerpts from his station diary. There are the maps and journal observations of Alan Arthur Davidson, the first white man to map the area around Mongrel Downs, now known as the Tanami Desert.

There are italicised passages of writing from Mahood’s artist’s journal: strange mystical writings of map1mking, mudmen and mysterious shadowy figures. And there are the anecdotes of those characters both black and white, some of whom she re-encounters on her quest, who populated her childhood. Then there is the narrator’s voice, that of Kim Mahood, retelling the stories of her father’s early life and recounting her trip back to the Tanami seeking answers to the question ‘… what is me and what is him …?’ It is the story of a woman alone in the outback with a second-hand ute, an ancient, toothless dog called Sam and an artist’s eye recapturing – or is she letting go of – the influence of Joe Mahood.

Mahood also writes of her mother, brothers and sister but unobtrusively and only where they are needed to flesh out the whole flawed man her father was. The reader is also given occasional oblique glimpses of the sensuous awakening of a teenager’s sexuality made all the more poignant because they are so fleeting. While on her journey Mahood hears of a big women’s business ceremony, something which was unimaginable in her childhood: ‘Then, the notion that Aboriginal women had any sort of power was absurd … philosophically I am excited by it, curious and hopeful.’ As a child Mahood was given the skin-name Pintapinta, or Butterfly, in the language of the Napurrula. When the time comes to be re-acquainted with the women, some of whom helped to raise her, she feels ‘ambivalent, embarrassed and an impostor’. She attends the ceremony and writes about it in a clear-eyed way again without excessive sentiment. In a prose poem which acts as an Introduction or Foreword to the memoir she writes in part: ‘The Black women gave me my old skin back/and made it new, / but I could not wear it. / The dreaming tracks are not mine.’

Writing of Lake Ruth, the lake of the title, Mahood says:

Later, when I drive to Lake Ruth, the sense of dislocation is even more intense … it is dry … The topography is utterlyfamili.ar. The boat is still here. My father brought it back from Adelaide and we all learned to sail. It lies like an abandoned folly on the edge of the dry lake … A craft for a dry lake, a vessel to carry the detritus of memory, marooned in the desert light.

And so Mahood’s journey is completed, the long conversation with her father ended, and most satisfyingly the answers to the questions raised no longer seem to matter.

Inevitable comparisons have been and will be made with Drusilla Modjeska’s Poppy, a memoir of her relationship with her mother, and Tracks, Robyn Davidson’s account of her camel trek across the desert to Western Australia. Mahood says her own response after first reading Tracks was that it was ‘too close for comfort. She articulated too clearly the complicated impulses and female messiness and fears I hated in myself.’ In contrast, her father was ‘hugely impressed by her [Davidson’s] achievement and found her introspection distasteful.’ Others will draw their own conclusions.

Comments powered by CComment