- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Interview

- Custom Article Title: An interview with Thea Astley

- Review Article: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The whole of inland Australia is manoeuvred, manipulated by the weather and by seasons, especially if you are in primary industry. I always like the story, I was travelling north once on the plane and the person next to me said that they hadn’t had rain for seven years. They were living out around Mt Isa and the first time it fell, his five-year-old ran in screaming with fright. But that’s probably one of those north Queensland stories.

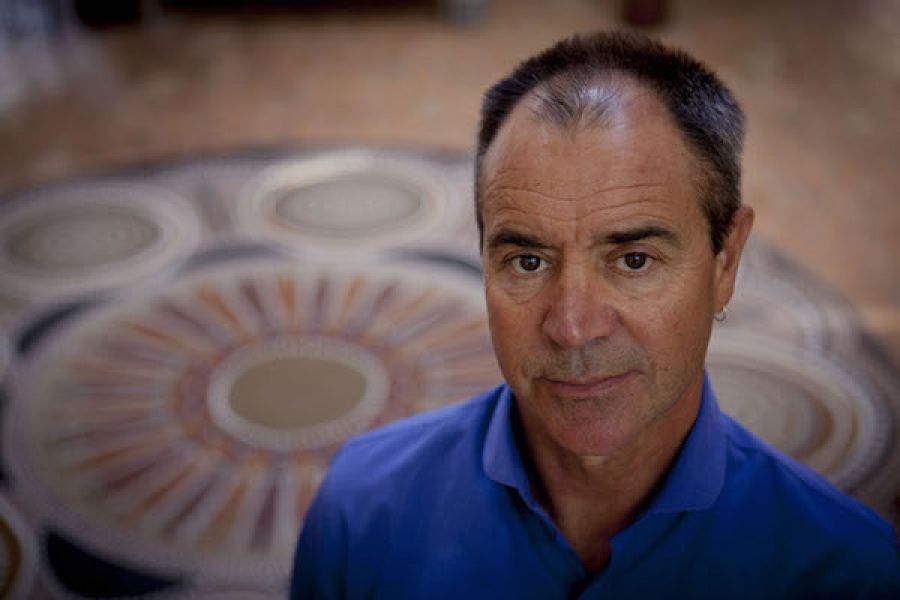

Ramona Koval interviews Thea Astley, co-winner of the Miles Franklin Literary Award for Drylands.

Ramona Koval: In a reversal of a trend in Australian fiction, which has novels set in wonderful little country towns with odd and amusing zany characters, you’ve set your new novel or collection of linked stories in Drylands, the town that everyone is dying to leave. Were you consciously aware of going against the tide in this particular setting?

Thea Astley: No, not at all actually. I’d just been motivated by constant newspaper stories of people living in the country and losing their services, and having to move out and towns dying as a result. I thought this is a very sad thing because I feel that the heart of Australia has depended for years, or the pulse beat of Australia, has been the work of pioneers who live in places that are almost inaccessible. Now they have cut out railways and there are few plane services that are regular and now they’ re removing banks, doctors, and hospitals. If the whole centre of the country dies, I think it would be appalling.

RK: Why do you think there is this city-based longing for these little country paradise towns that don’t really exist?

TA: Well they have existed. I don’t think people move inland they move to the coast after Sea Change. Everybody’s trying to get a little country town on the coast. They don’t want to go into the centre, perhaps because it is flatter, drier, and less picturesque.

RK: Well Janet Deakin says on the first page of Drylands that she has the wherewithal to write a book: table, typewriter, a new ream of paper and angry ideas. Do you agree with her? Is that what it takes to write a book?

TA: They used to say when I was a kid, one per cent inspiration, ninety-nine per cent perspiration. I think perseverance is the thing you need to write a book and I think writers are people who have been lucky enough to be gifted with the perseverance gene that makes them keep going when everything seems terrible.

RK: But what about the angry ideas?

TA: I think that’s important in a way. They haven’t got to be angry, they can be amused ideas, but they have to be ideas that are motivating or strong enough to provide an impulse.

RK: The book is very much about reading and writing. Could you begin to talk about the structure of the book, linked stories, linked also by the thread of the woman who’s writing them, Janet Deakin. How did you come upon this structure?

TA: I think Henry Lawson was the first to do what Frank Moorhouse calls ‘discontinuous narrative’. Lawson wrote stories using the same setting and with some of the characters reappearing. It’s rather appealing as a technique. The reason I think I have been interested in non-readers or non-reading is having taught at a university for a while and seeing kids coming up from high school who were sub-literate in their droves. I wonder what on earth was happening at the primary level of education. Weren’t they being taught to read? They certainly had no grammar and didn’t know much about the structure of the English language. I thought this was rather worrying. I’m glad that the department is, I think, moving back to basics.

RK: I think that inability to read theme is apparent throughout the book. There’s Janet’s husband, Ted, whom she teaches to read. There are the townspeople who don’t buy any books from her. Janet remembers her mother saying, ‘The more illiterates, the easier for governments to supply slave labour to the wealthy.’ Is that something you agree with?

TA: The figures on sub-literacy in Australia have been increasing according to statistics you read in the paper. Yes I do think people are more easily manipulated when they don’t have access to books or newspaper articles. Of course they have access to radio and television, but I imagine if places are privately owned there’s severe editing goes on in what’s expressed in news items. I don’t think the ABC does that but there’s always a bias. I think you’d have to be able to read to make up your mind around each side of a subject. Of course you’ve only got to think of the feudal system and just a few centuries ago in England where education was reserved for the wealthy, the privileged classes and schools didn’t offer much beyond the primary level. What interests me is the fact that when I was researching a couple of books I wrote a few years ago and I was reading letters written to local councils by people who had obviously left school at fourteen, they were impeccably written not a mistake in grammar, spelling or punctuation. They were infinitely better written than work I would get at university level.

RK: Janet Deakin also remarks about writing, ‘fly specks on white that can change ideologies or governments, induce wars, starvation or rare blessings’. Do you think they can?

TA: That’s what so marvellous about the printed word. I think the printed word is magic. Have you in tears or laughing uproariously. I think it’s wonderful.

RK: Something that nearly had me in tears was the story about Benny Showforth, the part Aboriginal man who was taken from his mother and then had almost everything taken from him by the people running the town. Tell me the story of Benny.

TA: Well the government was still removing children from parents in the middle 60s. When we were living on the banks of the Barron River outside Cairns some years ago, there was a little settlement of Indigenous Australians who’d been moved from Mona Mona mission. They were absolutely lovely people, very gentle, very quiet, and we always gave them lifts into town. I became quite interested in their quality of lifestyle. At that stage, the council had not connected the electricity because they said they would not pay their bills. There was an attitude all round that they were totally irresponsible. This annoyed me. I think Benny Showforth’s problem is probably basically quite true from all the stories I’ve read and heard and people I’ve spoken to.

RK: It seems that these stories are all related in some way to the seven deadly sins. Is that correct and can you explain how they relate to them?

TA: I had thought of the seven deadly sins when I’d started writing but I didn’t think I could handle them. And anyway people have done this before. I was just using incidents that I’d heard of in other places. I don’t even remember where some of the ideas came from. I do know that someone I knew once spent ages building a dinghy and his son burnt it, which came into the boatbuilding story.

RK: One of the characters says, ‘So little that is punishable in any ethical society is punished in this one.’ I had the sense that this was what you were saying. There’s a lot going on in Drylands that is really about people behaving badly.

TA: I think in smaller communities the misdemeanours and transgressions of local social people show up very promptly and because a community is small it’s more likely to bring some kind of retribution on the perpetrator, either verbally or physically. Whereas in big cities, probably why they are so popular, there is more anonymity.

RK: You write about creative writing classes, if we can come back to the writing. Evie comes to Drylands to teach a group of women to write, unleashing all kinds of miseries. The narrator says, ‘She was hating herself, these weary, expect ant faces. She hated herself and what she was supposed to be doing, floundering between their hope and their hopeless ness.’ It’s a pretty bleak view of the travelling writer who is coming to do a creative writing class in one of these towns.

TA: Later on in the story it says she was filling in for the regular tutor who went there now and again. Yes, I suppose it is bleak but I don’t really believe you can’t teach creativity, you can teach techniques and you can give people ideas of how to handle prose or poetry but you couldn’t teach Mozart to be a genius.

RK: Do you think there is folly in these kinds of classes?

TA: Not if they’re giving people a chance to get out and communicate with other people. I think that’s a very good thing. I don’t think it matters if people go to painting classes and can only paint stick figures and that would be me I think the fact that they are trying is something.

RK: The town Drylands is being outmanoeuvred by the weather, which comes through throughout the book. In a sense, it’s the thing that makes us realise we are all pretty vulnerable, all of us no matter who we are, whether we are insiders or outsiders.

TA: The whole of inland Australia is manoeuvred, manipulated by the weather and by seasons, especially if you are in primary industry. I always like the story, I was travelling north once on the plane and the person next to me said that they hadn’t had rain for seven years. They were living out around Mt Isa and the first time it fell, his five-year-old ran in screaming with fright. But that’s probably one of those north Queensland stories.

RK: Some people might say Drylands is a bleak book, bleak about small towns, bleak about the economy, about the falling literacy rate, about mean people. What would you say to that?

TA: I might have to agree. Maybe I was feeling bleak when I wrote it. I’m feeling bleak with these constant reports of towns closing down and that’s what stimulated me in the first place.

RK: Do you think this is about Australia in particular or about human beings in general?

TA: I think it’s more general. I think when humans are confronted with an almost political posse that’s bringing about the death of their small Eden, I think it applies generally.

RK: It is a deeply political book but it is actually written with a very light touch. It’s not a campaigning book.

TA: No it’s not. When I think of the joyousness with which I wrote a book like It’s Raining in Mango, I’ve always liked laughing and I like it to come through in my writing if it can. But I guess I didn’t feel much like laughing when I wrote Drylands.

RK: Finally, Thea, how do you feel about the Miles Franklin for the fourth time?

TA: Very surprised. Quite pleased and very surprised and very happy to be sharing it with Kim Scott. I have read Benang and found it very moving.