- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A legacy of reform

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘Dick Downing had a keen sense of what would make Australia a better country – for a strongly welfare minded economist – the knack of being in the right place at the right time.’ Thus Nicholas Brown, in his subtle and intelligent account of one of the shapers of Australia in the twentieth century.

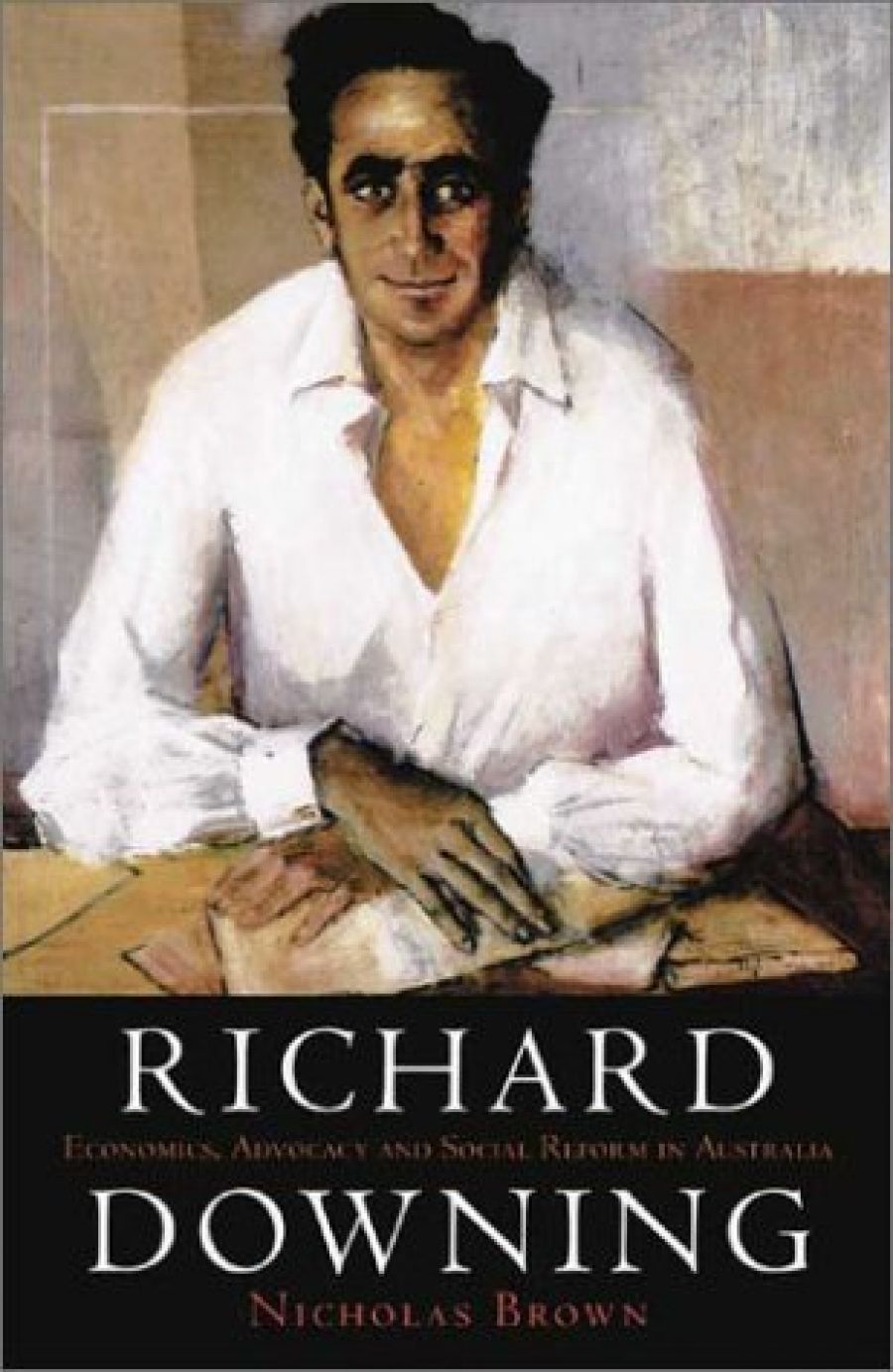

- Book 1 Title: Richard Downing

- Book 1 Subtitle: Economics, advocacy and social reform in Australia

- Book 1 Biblio: MUP, 346 pp, $49.95 hb

It is twenty-six years since Richard Downing’s time ended. He died, at sixty, on 10 November 1975, the day before the dismissal of the Whitlam government. The quarter century since has seen the unravelling of much of the social reform initiated by his remarkable generation of economists, public servants and public thinkers. It has also seen the erosion of the tradition of public advocacy and broad social concern for which he stood.

What would Downing have made of the most recent federal election, held as it was on the anniversary of his death? The irony, at least, he would have relished. In an earlier, dark moment, October 1975, he asked his fellow economist and contemporary in public life, Nugget Coombs: ‘Am I insane in being grateful for having experienced the last few weeks? I’ve lived with Bruce, Page, Lyons, Menzies, Fadden, McEwan, Holt, McMahon, Snedden and Anthony and so on – without ever having seen such naked and obscene indecency as Fraser has managed to reveal – of absolute intolerance of the idea of Labor in office.’

Times change. Malcolm Fraser, once avid for power, is now the conscientious elder statesman and most outspoken critic of the conservative style of politics that succeeded his own, more liberal era. He publicly repudiates the cast of mind that crafted the economic and social politics of the 2001 Coalition victory. Brown’s deft conclusion might now serve as well for Fraser as it does for his subject: ‘Downing despised the political rhetoric of ‘the taxpayer’ and all it represented – the fear and insularity; the lack of generosity; the failure of conscience in the placement of self before society.’

Downing had indeed ‘lived with’ a variety of governments. He was that increasingly rare specimen, a public servant and sometime academic advisor, able and willing to offer all political comers his conscientious and independent advice – before Sir Humphrey devalued the currency. What was so striking about Downing (indeed about many of his contemporaries on both sides of the political order) was the depth of that ability. One of the sharper revelations of this study is the sore loss to government, and therefore to the people, of the breadth of independent intellectual resource that a more secure era took for granted. In a nation that has politicised the public service, advice now wears a muzzle.

Nicholas Brown is modest in his claims for this book. It is not, he says, ‘a biography in the full sense of the term’. That is true: it is more a scrupulous description than a critical assessment. Richard Downing fitted a great deal into his sixty years of life, and part of the record is locked away. The much travelled and celebrated public man of affairs also lived privately for many years as the companion of composer Dorian Le Gallienne. Le Gallienne died in 1963. Two years later, Downing married Jean Norman. It is a matter of some regret to Brown that the correspondence between Downing and Le Gallienne was deposited by Downing in the La Trobe Library on the condition that it not be opened until after his death and the death of his wife, of her six children and of the daughter they shared. One can understand the itching frustration of the writer but, at the same time, appreciate the way in which Brown makes a virtue out of the necessary deflection of his attention. This is very much a book about economics, advocacy and social reform, but one mediated by a distinctive sympathy and understanding for the ‘presence’ of the man who embodied the Keynesian abstractions.

It is a critical account – Brown is no hagiographer – but it is stylistically in tune with its subject. There is a diffidence in the writing, and an ironic bite to it that Dick Downing would have appreciated, even as he winced. And there is pleasure to be had, even in its discretion. Downing and Le Gallienne, and afterwards Downing and Jean Norman, paid their dues to public life; who would begrudge them their brief span of privacy? There is also something admirable about the ‘circle of discretion’ friends and colleagues drew around them. Bohemian privilege? Yes. Harm done? It’s hard to see what harm, or what could be gained from prurient intrusion. In any case, Brown is so thorough and perceptive about the influence of love and family in interlocking public and private lives. Le Gallienne is a necessary presence and part of the explanation of Downing’s many public stances. The Downing who became chairman of the ABC in June 1973 owed much to the musical integrity of the man with whom he had shared so much of his life. The Canberra bureaucrat also became the denizen, with Le Gallienne, of one of the most environmentally attuned – and exciting – houses of its period, built for the couple in Eltham by Alastair Knox. The house was to be serially extended as Downing’s circumstances changed. There the late-come family man was to use his and Jean’s children as controls when forming his views on popular (and unpopular) television and issues of censorship.

Brown is also acute, without a trace of intrusive psychologising, about class background and the marks left by the Depression, about fathers (in Downing’s case, absent, though exacting), mothers (formative) and the affections that flow from intellectual mentoring.

It is with Downing’s university mentors that the book moves into its full intellectual progress – an integrated account of the role economic theory played in the shaping of Australia between 1930 and the mid-1970s. Downing studied Economics at the University of Melbourne under D.B. Copland and L.F. Giblin. Both men had their impact on the scholarship boy from Scotch College, not least in the way their academic and public roles were fused. As advisors to government, they provided the pattern, and, as human beings, they encouraged the scholar and the young man. Downing remembers himself ‘bouncing into [Giblin’s] room one morning – I was nineteen, he was sixty-two – full of enthusiasm about some Bach I’d been listening to. I loved him, not just for his teaching, but also for his kindness and gentleness.’

After Melbourne came Cambridge, and Keynes’s General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. Downing was on his way. It was to take him backwards and forwards through academic life, the Canberra bureaucracy, the International Labour Office and the ABC.

Brown’s account is detailed, satisfying to both the professional economist and the general reader. As a history of a public life, it is both astute and prophetic. Brown is immune to nostalgia and too aware of Downing’s complexities – the privilege, the openness, the vibrant presence and the calculated withholding – to make a hero of his subject. But the life he describes is eloquent enough to spur reassessment of the way in which we now order our society. For Richard Downing, as Geoffrey Harcourt wrote in The Times, economics, was ‘first and foremost a moral science’.

That is a legacy worth reviving.

Comments powered by CComment