- Free Article: No

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Chris Wallace-Crabbe’s new book, By and Large, is, despite its hundred pages, a thinner book than most of his recent volumes. The familiar features are there: a baroque and intense intellectual ambit combined with playfulness; a deep love of the sharp ‘thinginess’ of the world combined with a love of the expressiveness of the words we use to contain it; and, last but far from least, enjoyable phrasemaking. It is just that, in By and Large, the reader’s pleasure seems more attenuated.

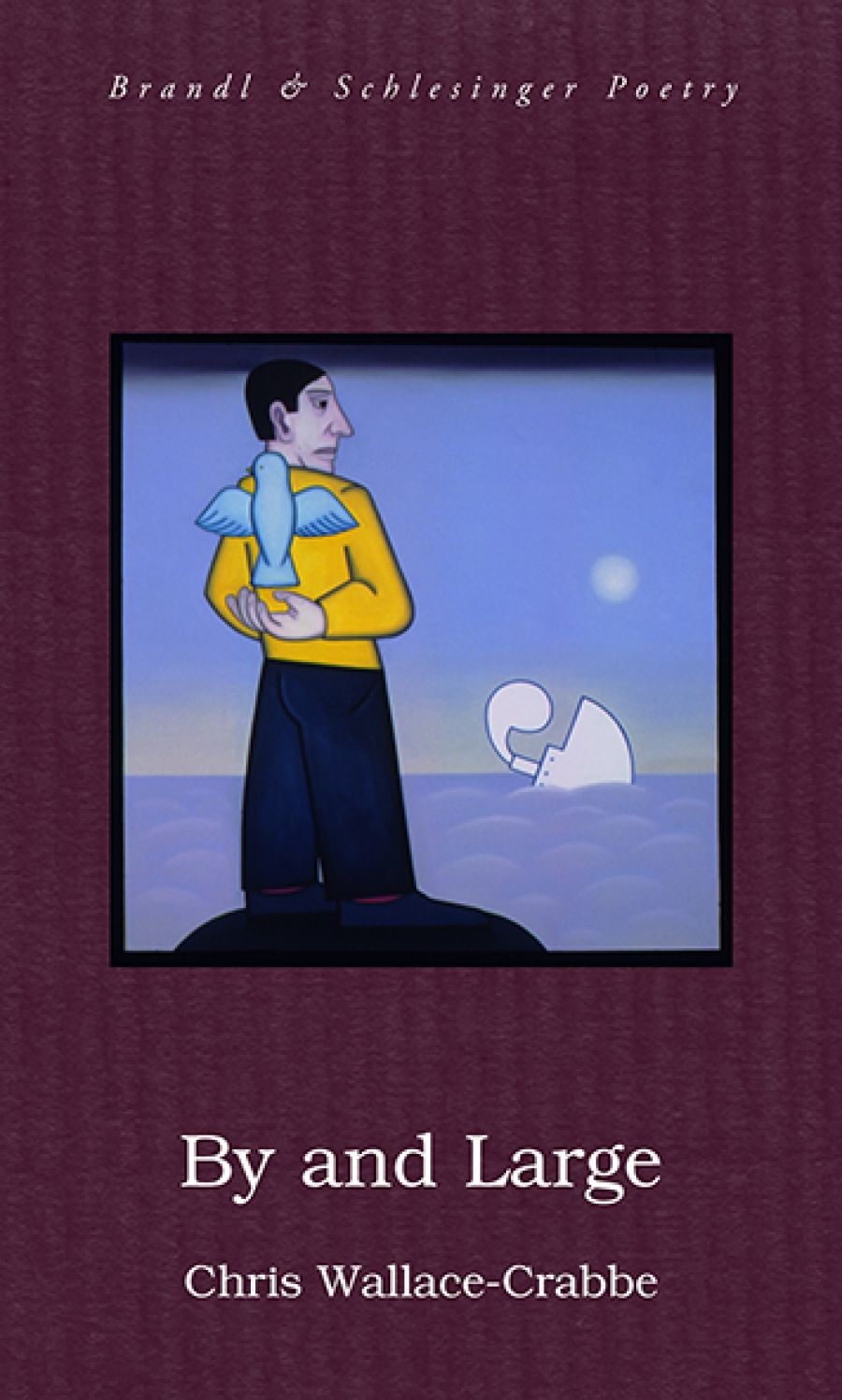

- Book 1 Title: By and Large

- Book 1 Biblio: Brandl & Schlesinger, $21.95 pb, 98 pp

‘Modern Times’ has a journal-like quality and a deliberately rough finish. It might well be a charm to ward off a fear on the author’s part that there is a kind of primness about his poetry, a tendency to wrap up an incomprehensible world, and the garbled quality of life as it is lived now, in a beautiful package.

It is full of deliberate vulgarities: terrible jokes that only a Freudian could love (the first poem, set in Canberra, begins ‘Crumbs, it is capital to be here’); ‘bad’ language (‘it’s pretty tough / To be a PoMo shithead jacking off’), and some fairly brusque technique. It even, interestingly, contains an unfinished sonnet – a Holocaust sonnet, both unsayable and unfinishable perhaps, but a fragment nevertheless.

The sequence begins and ends with Canberra and, on the way, touches on a host of suitably ‘external’ topics: government, Nazism, globalisation, Freud (‘among whose pillars we are dozing’, ‘still draining the psyche’s muddy Zuyder Zee’) Marx and Western civilisation, postmodernism, and so on.

But it is also often about the interior life: dreams figure largely – there is a dream poem in French – as does the nature of the self. Similarly, just as it is about external and internal, it is also about macro and micro. Big History and local History both have their say. The former, using the widest-angle lens possible, produces poem XXXII:

After the golden age of leathery shepherds

they came around to having kings.The old kings were easily knocked over

by khaki traders with guns.Revolutionary discipline, jeunesse and hope

gave colonizers the shove – in their turn –but the cool, wired-up multi-nats

got rid of such boring bureaucracies.

But intimate, local history appears in the form of poems about the poet’s return to his Melbourne home.

Fittingly for a sequence interested in movement, it is often interested in spaces. One of these is the gap between biology and culture. It is, as one poem notes, a long way between the need to feed the body and ‘jaffles / let alone cassoulet’. It is also interested in the writer’s position as user of language and used by language. One of the best poems describes the tension between the desire for verbal incarnation:

Part of myself would love to master

Versatile verses that might contain

Bamboozle, billycart, bonk and bonzer,

Teasing language to fill up the frame.I’d lay the pigments on like van Gogh

(Daub, dazzle, design, and dread)

Treating the page with dense impasto

And the wider perspective on the human situation:

But in the other lobe, I respect

The way that Gaia might look at us,

Located in between oak and insect,

Introspective and querulous …

None of this should surprise us, since ‘Modern Times’ is a sequence that attempts to record life in the act of living, consuming, reading, and thinking. In other words, it is not the subjects in themselves that the author is investing in but rather the totality and the linkages, the processes of moving from one moment of life to another. This seems fair enough: we are all suspended between the incomprehensibility of history and the incomprehensibility of our inner lives. The final poem returns to the former – ‘What does Australia mean?’ – and concludes with the interior and the local:

From Queanbeyan to dovegrey Paris now

There rise in broken, dopey ranks

The newer generations of despair;

Saved by odd loyalties, some god knows how,

And, reborn many times, I give my thanks

For psychic spaces, and this aromatic blue air.

The first and third sections have much in common. They take the sort of material that ‘Modern Life’ deals with and isolate it out as separate, more conventional poems. These seldom match the best of Wallace-Crabbe’s work, but that is not to say that there are not memorable poems. ‘Amid the Comings and Goings’ is a serio-comic piece of diarising which suggests that, in an extended mode, it might perform something of the same function as the middle section. ‘Presentables’ and ‘Knowing the Score’ are potent meditations and there are at least two very fine and resonant lyrics, ‘Post Script’ and ‘Low Tide Walk’. The latter concludes – and it is a conclusion many of the poems arrive at – ‘A meaning of my life is far beyond my reach’.

One of the poems from the first section, ‘Easter Day’, reworks the theme of immanence versus cosmic perspective, alluded to above, into a fine poem. After brilliantly describing the effect of the ‘soft north wind’ on trees, the poem goes on to ask:

Does art consist in trying to copy this down

in verbs or little strokes,

in daubs and melodies?Maybe it does, but there has been

another order, one somehow in which

the artist, poor soul, offered to transcribe

epiphanies like

amazing refugees fording the Red Sea

or Christ is risen.

It is a continuing debate in the book. It draws attention to one of Wallace-Crabbe’s pleasure-giving skills, the ability to exploit the expressive power of his ‘bonzers’ and ‘bamboozles’. The collection is full of strangely tactile, demotic, and yet weirdly expressive words. In ‘A Vignette’, for example, the man ‘across the pubby smalltalk’ gives his secret partner ‘a hot, strippy look’, our conventional processes of eating and drinking become ‘nibble and quaff’, and voters have ‘tidgy’ hopes and fears. It may be no more than a poet’s basic technique, but it stands out in this poetry perhaps because it is a poetry that so often concerns itself with the significance of expressiveness.

Comments powered by CComment