- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Theatre

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The theatre of intoxication

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

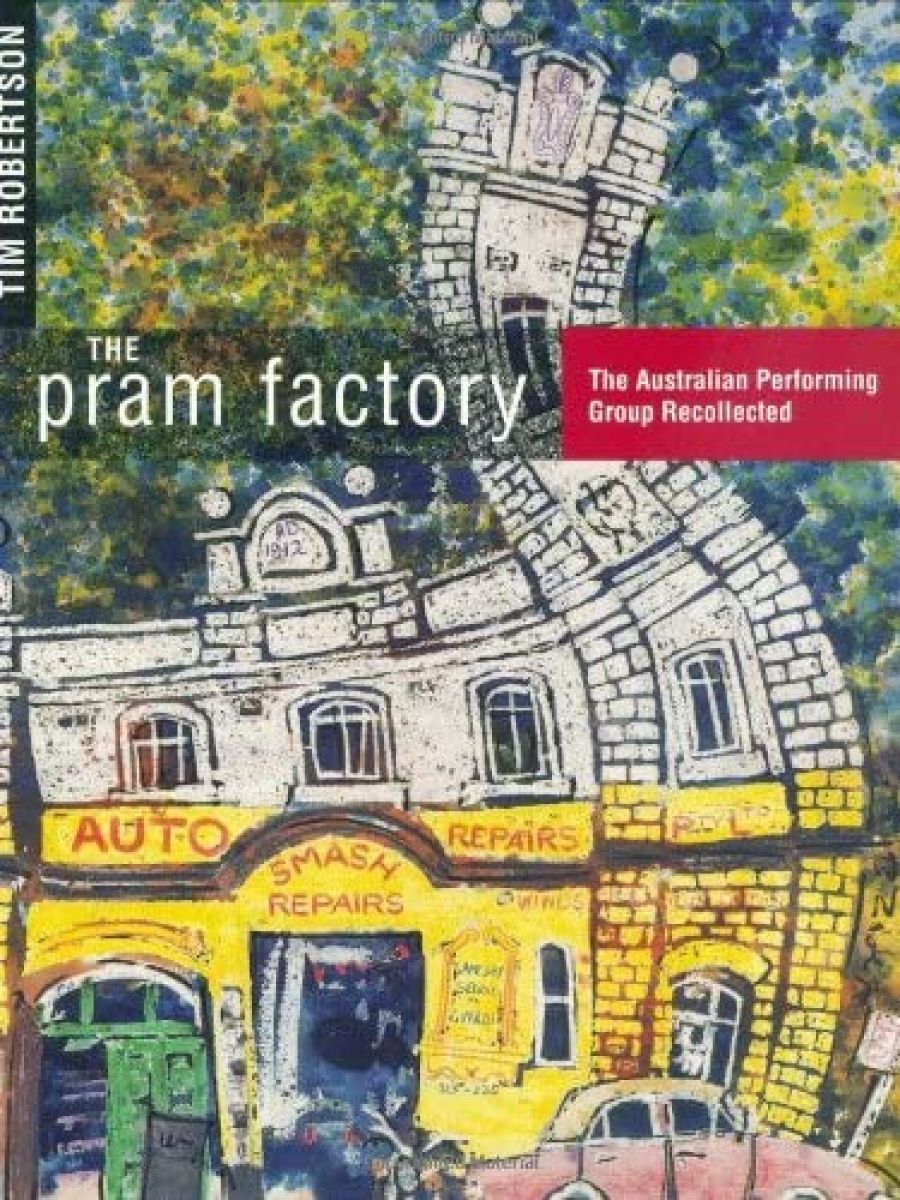

At last a history, thirty-two years after the event, of the Australian Performing Group (APG), albeit in the form of highly personal ‘recollections’ from Tim Robertson, one of the group’s stalwarts. The Pram Factory is a handsome, large-format book, containing many wonderful photographs recording the young radicals of the 1970s who created Australian theatre history.

- Book 1 Title: The Pram Factory

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Australian Performing Group recollected

- Book 1 Biblio: MUP, $39.95pb, 179pp

His style can be irritating. Freewheeling, noun- and adjective-laden, hyperbolic, grammar-challenging, it seeks to convey the uniquely iconoclastic lifestyle, politics, artistic practice, ambience, and sheer cheek of the group of theatre workers – performers, writers, welders, teachers, directors, plumbers, and sometimes drug-hungry desperadoes – that made up the APG.

Sometimes this style works, as in the wonderfully illuminating account of the lengthy, messy development of the Hills Family Show (a production Robertson describes as the ‘summa of group creation for the Pram’), or in the character portraits of the participants. At other times, it is strained by self-consciousness and becomes breathless with the attempt to reproduce the psychedelic life and art performances of this particular alternative culture. Hysteria is sometimes not far away.

Nevertheless, only a participant could convey convincingly the sheer excitement of being part of this group. There will no doubt be other historians who will provide analysis in place of the sense of process that Robertson creates. They will draw our attention to the political and social context (in fairness, sometimes touched upon by Robertson with considerable irony), such as the fact that it was the Liberal government’s opening up university places to the lower middle- and working-class children of the 1960s that was a crucial factor in liberating the APG’s anarchic creativity.

The book is a companion volume, particularly for theatre historians, to the history of La Mama that Helen Garner co-wrote with Liz Jones and Betty Burstall in 1988, and she provides a foreword here.

Len Radic’s brief but fair account of the APG in the Companion to Theatre in Australia (1995) gives it credit for tipping the balance of theatre programming towards the local and for developing a highly physicalised playing style, noting a handful of plays originating in the group that have entered the Australian theatrical canon. This modest appraisal is in stark contrast to Robertson’s (and others’) sense of genuine radicalism and unique democratising of an otherwise exclusively ‘high’ art form.

The APG politicised theatrical practice, delivering their irreverent verdict on their parents’ generation’s respectability by looking up the skirts of Cardinal Mannix (Barry Oakley, The Feet of Daniel Mannix, 1971) and cutting Robert Menzies down to size (Barry Oakley, Beware of Imitations, 1973). Comic though such plays may have been, the group had a sharper political edge than Sydney’s Nimrod, and tackled tough issues like racism in plays such as John Romeril’s Bastardy (1970), Alex Buzo’s Norm and Ahmed (1970) and Katharine Susannah Prichard’s 1927 play Brumby Innes, which received its first production there in 1972. Many shows were performed in factories and on the street.

Robertson signals at times his awareness, with appropriate irony, of the paradoxes involved: the university education of most group members and identification with the working class by individuals already well on their way up, who were often caught between competing claims of ideology and practice.

The demise of the group in 1980, symbolically dating from the auction of the Pram Factory premises, was inevitable. Only youth could sustain the lifestyles and artistic practices so atmospherically described, in all their mess and muddle and passion. And alas, the several premature deaths recorded in the Who is Who section signal the danger of lives often self-destructively fuelled by excess, including alcohol and drugs.

The cancer in the bud of the APG alternative theatre was there as early as 1970, two years after its formation, when the first grant of $2000 from the Drama Board of the Arts Council was given to the group for the development of Marvellous Melbourne. Claims to radical social criticism were thereafter fatally undermined by compliance with funding bodies’ criteria. There is an engagingly candid account of political opportunism that resulted in a $50,000 grant to the APG from the Hamer government. This followed the assiduous and street-smart courtship of the Liberals by some of the group’s leading lights, making good the damage attributed to an unwise attempt to force the uncooperative Whitlams into audience participation at the Sonia Knee and Thigh Show in 1972. It is for such insider revelations that many readers will value this book.

Similarly interesting are the complex accounts of some of the legendary group meetings where tactics that would not have been out of place at a builders-labourers’ stoush were customary. Robertson shrewdly notes at one point:

In circumstances of egalitarian political correctness the possession of performance talent could be a liability, seen as a threat. The naturals and those of proven track record had to exercise much tact and diplomacy for fear of being thought to be getting above their station.

Playwrights and women did not fare well in such a milieu. ‘Female parts were hard to come by,’ Robertson suggests, tongue-in-cheek given the book’s chronicle of sexual anarchy too complex to untangle most of the time. In 1973, the women formed the Women’s Theatre Group (only rarely making it to the Front theatre, though), preceded in 1972 by the feminist show Betty Can Jump.

The playwrights were sidelined for several reasons, and Robertson remains true to the faith in arguing that the genius of the Pram was not to be found in its playwrights but in its performers, and more particularly in the ‘ephemera’ of performances such as the late-night Supper Show.

Robertson remains a true believer in the romance of this era and this unique group. His stylistic pyrotechnics evoke some of the mayhem of the twelve years of the APG, never more endearingly than in his final, affectionate portraits of Peter Cummins, John Romeril, and Tim Coldwell. This last chapter also provides an invaluable account of the APG’s most lasting legacy, Circus Oz, from its inception to the present day. This also suggests that his earlier argument pitting text against performance has some real truth to it. It is in Circus Oz that the irreverent, physical, spectacle-making style of the original group has found its most durable form.

The writers who survived the baptism of fire that was an APG committee meeting have, with a few notable exceptions, gone on to other things. Barry Oakley has put on record the pain of having his work derided and revised by the performers, top of the APG food chain, and also the strategy of ultimately, but quietly, ignoring them in the end. David Williamson retired hurt, but has had the last laugh in terms of fame and fortune.

Jack Hibberd and John Romeril proved winners in the ring (Romeril by performing three-hour epic harangues at the Business Arising point of proceedings). Both have been prolific writers, yet, putting aside the commercial (and other) success of Hibberd’s Dimboola and A Stretch of the Imagination, and Romeril’s The Floating World, they have remained true to their original faith in theatre as a terrier worrying the heels of bourgeois respectability. They thus embody the Pram’s central paradox: success was anathema to the project of social criticism. This is why grant applications inevitably sowed the seeds of self-destruction for the group.

The book puts on record, pictorially and verbally, some marvellous performance moments, properly putting the performers themselves in first place. Actors such as Max Gillies, Bruce Spence, Evelyn Krape, Graeme Blundell, Sue Ingleton, to name only a few, are affectionately recalled in their younger manifestations, in rollicking, Rabelaisian style.

Robertson’s is the first rather than the last word on this chapter of our theatre history. His retrospective irony just about balances his understandable celebrating of what was, after all, his own part in history, his own youthful rite of passage in the counter-cultural years of the late 1960s and the 1970s.

Writing this book must have been as tricky as getting a motion passed at an APG meeting. A fierce in-group, one that aggressively patrolled its borders and sniffed out the politically incorrect at any opportunity, the APG was not universally loved. It was ironically as exclusive in its way as the respectable, conventional theatre it sought to challenge. Robertson wobbles sometimes on his tightrope, cleverly employing wit, irony, and verbal inventiveness to reveal the group from both inside and out. But he succeeds, in the end, in evoking the manic excitement, the fierce living out of the political in the personal, the necessary jettisoning of two decades of postwar conformity, which fuelled a remarkable phenomenon. Like so many Pram productions, the book enacts a process that subsumes product. It recreates an intoxicating era, giving a potent sense of what it was like to be there, in the eye of the counter-cultural storm of the 1970s.

Comments powered by CComment