- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Step by step

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Selling books is a difficult business. Publishing, too. Booksellers and publishers need courage and imagination. A book about a contemporary Federal politician with the adjective ‘new’ in the title displays both these qualities. Tony Blair may have got away with ‘New Labour’ in Britain. In Australia, a large part of the disenchantment with politics and politicians stems from the feeling that, apart from the fresh face of Natasha Stott-Despoja, there’s nothing new around; no new ideas, no articulated vision of where the country might be in ten- or twenty-years’ time, nothing inspirational. Perhaps something might emerge before the next election. But no one’s holding their breath.

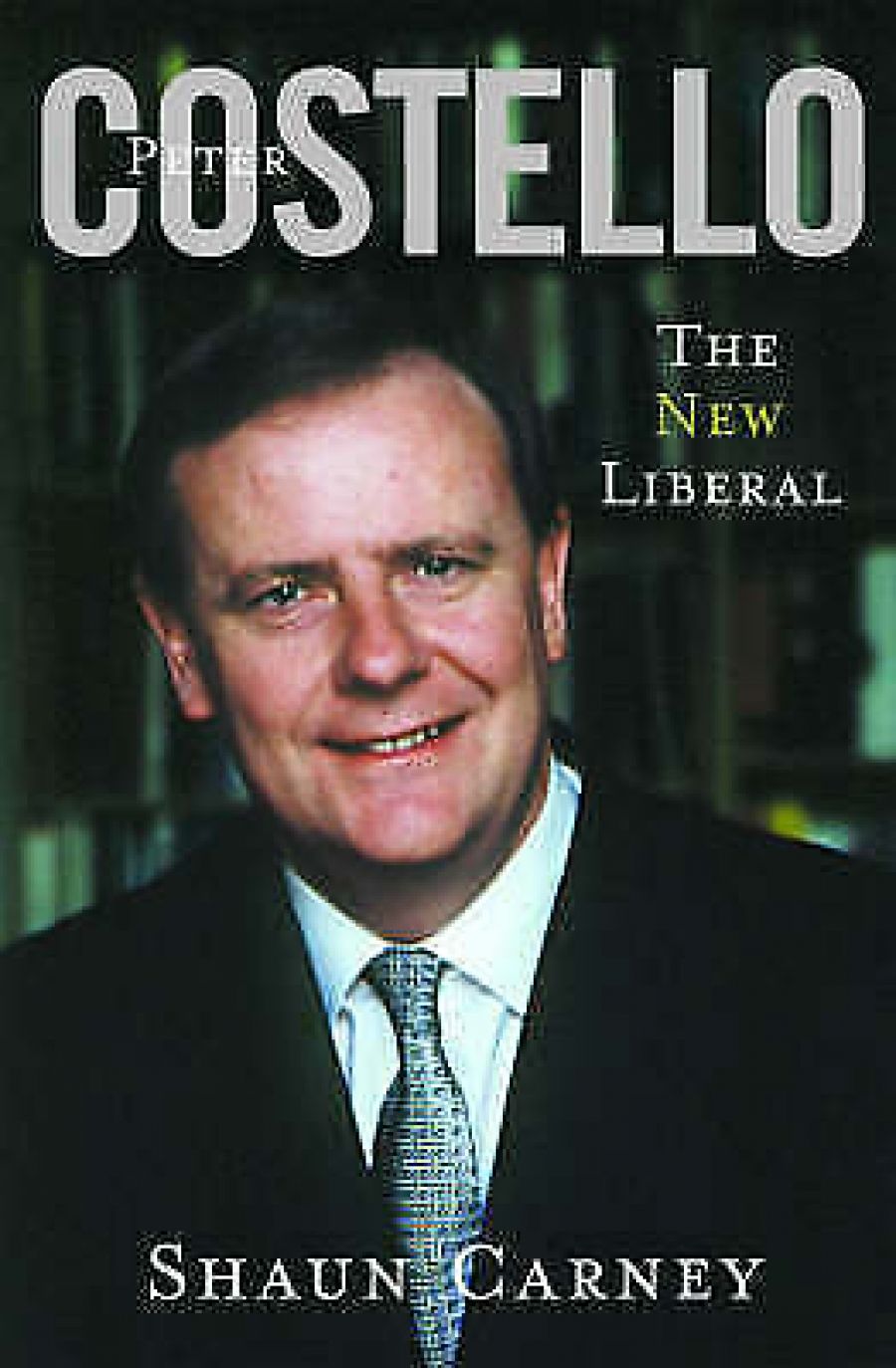

- Book 1 Title: Peter Costello

- Book 1 Subtitle: The new Liberal

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $29.95pb, 351pp

All the signs, surveys, focus groups, radio talkbacks, flirtations with maverick independents, show that Australians are looking for something better from Canberra. And they have vestigial hope. So the word ‘new’ in the title is not so stupid after all. It’s based on the theory that hope usually triumphs over experience. People might buy the book hoping for the revelation of a ‘new Liberal’.

Most stories which touch on the obsessional characteristics of political life are somehow reminiscent of Bertolt Brecht’s play The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui. Peter Costello’s story is no exception, although his talents, ambition, and fortuitous circumstances have made his rise less resistible. One step has always led to another.

Costello was one of three children in a politically conservative Baptist household in the Melbourne suburb of Blackburn, in which ‘the key elements were hard work, discipline, self-improvement, and the worship of God’. The church dominated family life. As a child, he was one of the ‘crack troops’ of the Baptist Youth Organisation. He did well at school and practised his speaking skills on his Baptist brethren. At sixteen, he preached to a congregation of four hundred. There was not much social life beyond the church and the family. Television provided a rare window on the outside world and an early introduction to politics. He handed out his first Liberal how-to-vote cards in 1972, when he was fifteen. As a law student at Monash University, he was active in the Evangelical Union but, increasingly attracted by the political life, he obtained a ‘clearance’, which enabled him to participate actively in student politics, the province of Caesar rather than God. From then on, he was a student politician, who, in spite of a mild and opportunistic flirtation with right-wing ALP students, increasingly committed himself to conservative politics. He was good at it, both as a debater and organiser, in association with his close friend Michael Kroger.

After completing his law qualifications, Costello went to the bar, where he built a reputation as an effective opponent of bloody-minded trade unions; notably with the Dollar Sweets and Robe River cases. In 1986, he was a foundation member of the H.R. Nicholls Society, which quickly attracted the usual suspects of right-wing politics.

These early milestones led in only one direction, a political career, which to some had seemed his destiny from an early age. In 1990, aged thirty-three, he became the Liberal Member for the Melbourne suburban seat of Higgins. In Parliament, Costello suffered some of the setbacks and frustrations that seem to be the lot of the successful and ambitious, but soon developed his reputation as a debater and political ‘head-kicker’. In 1996, at the age of thirty-eight, he became federal treasurer, inheriting an economy which was, superficially at least, in good shape. Since then, he has been a hard-working minister, presiding over a period of steady economic growth and the difficult implementation of the GST. Now he waits, his eyes on the next step.

As one might expect from a journalist of Shaun Carney’s ability, this particular pilgrim’s progress is well written and thoroughly researched, providing a good background to the politics of the 1980s and 1990s. There is, however, a danger of disappointment for the hopeful reader. Many of Costello’s ideas, as they emerge in this book, are as ancient as those of Old King Cole or John Howard. There is not much refreshingly new about them. The reasons for this are fairly obvious. Costello, who, unusually in an unauthorised biography, gave ‘dozens of hours’ of interviews to the author, is constrained by a fragile loyalty to John Howard and by the persuasive political correctness which ‘dumbs down’ the public discussion of political ideas. ‘Followership’ is more in vogue than leadership. Political parties veer a little to the Left or a little to the Right according to the staccato command of opinion polls.

In this environment, it’s not easy to establish an identity. Although this book provides an honest portrait, it has a certain Pro Hart quality about it: glossy, hard-edged, decorative rather than profound.

Peter Costello is rightly regarded as a potential, indeed likely, future prime minister. This is largely based on past successes, but happily there are also hints of difference from the prototype politician. Unnamed colleagues suggest that he would be more compassionate with welfare and indigenous disadvantage, that he has an open mind about tackling the drug problem, and favours higher immigration. He is already on the record as supporting a Republic. He participated in the Reconciliation Walk in Melbourne.

However, it is on the larger issues such as the dwindling notions of ‘the fair go’ and equal opportunity (once the defining characteristics of Australian democracy), on environmental problems, on Australia’s role in the Asia–Pacific region, on finding new paths to wealth creation for a predominantly ‘old economy’ that the reader is left in the dark. If only, during all those hours of interviews, the author had asked one more question: ‘Mr Costello, on these questions of underlying concern, what do you believe?’ The answers to such questions are not to be found in a Treasury brief, and they are not in this book. If they had been it might have done much for Costello’s credibility. Instead, we are left with a man who is undoubtedly clever but with ‘only one certainty: his self-belief’.

The public image reflects this. He’s seen as ‘smart’, ‘smarmy’, a man who smirks and ‘looks as if he has a nasty streak’. He lacks the natural wit of Whitlam or Keating, the gravitas of Fraser, the popular appeal of Hawke or the earthy charm of Gorton. He is not, as one of his colleagues put it, ‘a knockabout bloke’. Why would he be, having followed the straight and narrow path through life, as described in this biography? But perhaps he’s clever enough to overcome these deficiencies. If so, there could be a sequel in which the author has richer material to work on.

Comments powered by CComment