- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘People are not entitled in a civil society to pursue a malicious campaign of character assassination based on a big lie.’ This was Andrew Clark, son of the historian Manning Clark, expressing understandable outrage on behalf of his family. The issue was the infamous allegation, based on nebulous evidence, that Manning was ‘an agent of Soviet influence’ and had been awarded the Order of Lenin. Unfortunately, as the Clarks will know, the big lie, even when refuted, spreads across generations. Although the onus is supposed to be on the accusers to prove their allegations, in reality it is easily, plausibly reversed.

The descendants of John Wren (1871–1953) are less fortunate than those of Manning Clark. They see their forebear pilloried as a gangster – Australia’s Al Capone, according to Frank Hardy – in publications less transient than newspaper columns, less subject to doubt than a popular novel. In fact, his alleged infamy has been immortalised in Clark’s own A History of Australia, Volume V (1981), in a chapter entitled ‘Embourgeoisement’.

However, anyone who thinks that Power Without Glory (PWG) is read just as ‘composite fiction’ rather than as history should read Dorothy Hewett’s letter in ABR (April 2001) in which she states that Hardy exposes ‘the villainy and corruption in right-wing Victorian Labor politics, and amongst some leading figures in the Catholic Church’ (obviously Archbishop Daniel Mannix, in particular). Even the fantasised adultery of Ellen Wren (‘Nellie West’ in PWG) is accepted as fact, ‘a commendable act’, while the disgraced ex-copper Bill Egan (‘Bill Evans’) becomes someone better than Hardy seems to have intended – ‘a decent working-class man’. It says a lot for Hardy’s ‘research’ that he dates the affair and its termination at 1917, though the child, Xavier, allegedly conceived as a result, was not born until 27 October 1919, an elephantine gestation, but not beyond the Hewett–Hardy imagining. Quite bluntly, Hewett knows little about the issues raised in PWG – but, watch this space, that will never stop her. As for her praise of Hardy’s honesty in exposing Soviet Communism in his 1969 Bulletin series, ‘Stalin’s Heirs’, this surely has to be put beside his Journey into the Future (1952) where, to adapt an old party jibe, he played the (left-fascist) running dog for the Soviet Union – at a considerable profit, as Hewett concedes. Hardy played the smoodger to the limit of credibility. Shall we praise him for being forced to wake up? Hewett apparently believes that being a ‘writer’ excuses anything, even craven stupidity.

Hardy, who had some collaboration with Clark as early as the 1940s, claimed he was the historian’s consultant on Wren – and that is how it looks. Clark is quite astray even on Wren’s birthdate: ‘probably in 1865’, he wrote. However, he did not need to send his research assistant to the Registrar to get it right. The Australian Encyclopaedia of 1958 puts it correctly at 3 April 1871, as do others. Clark ostensibly footnotes his sources. They are merely the article ‘John Wren and his Ruffians’ in the first issue of the Lone Hand (1 May 1907), thirteen arbitrarily selected pages from Keith Dunstan’s Wowsers (1968), two discrete, uninformative paragraphs taken from the Bulletin (4 and 27 October 1906, respectively), and ‘a file of newspaper cuttings’ in the National Library of Australia, which turn out to be thin, recent and uninformative. There is no mention of two books tolerant of Wren: Hugh Buggy’s too laudatory The Real John Wren (1976) and Niall Brennan’s critical and patronising but not unsympathetic John Wren, Gambler (1971). Buggy knew Wren well from 1915; Brennan’s father, Frank, attorney-general from 1929 to 1932 in Scullin’s government, earlier. One would have thought the two books offered something. So, for a credible contemporary source, Clark had only the scathing, seminal Lone Hand article, published anonymously but written by a notable journalist, Monty Grover (1870–1943), the future founding editor of the Sun News-Pictorial.

However, before seeing what Clark does with Grover, let us consider the most heinous crimes imputed to Wren in PWG, which Hardy and his Stalinist masters wished to be accepted as history. Because the alleged adultery of Ellen Wren (‘Nellie West’) was the subject of the sensational criminal libel case of 1951, and for reasons of prurience, attention has been diverted from the four murders in which ‘John West’ (Wren) is implicated. The first of these arose from an alleged attempt by Wren and his cousin, J.B. Cullen, to suborn a witness, Arthur Smythe (‘Stacey’ in PWG), ‘this unstable blacksmith’, as Grover calls him. As described in PWG, the court cases involved degenerate into farce. Actually, Wren and Cullen were exonerated and the police severely castigated. Grover stops there, but not Hardy. He concocts a sequel in which ‘Stacey’ is kidnapped with violence from police custody at the portal of the ‘Carringbush’ (Collingwood) court, an impossibility without its being reported in the newspapers. Ultimately, ‘Stacey’ is shanghaied and disposed of at sea from a ship dealing in drugs and prostitution. But Smythe almost certainly died in the Alfred Hospital in 1939. In line with communist policy of discrediting the judiciary, an honourable judge, (Sir) Joseph Hood (1846–1922) is accused of having accepted 400 sovereigns to misdirect the jury in Wren’s favour. Only Hardy, a stranger to the concept, has ever impugned Hood’s integrity.

‘West’ is also said to be involved in the getaway car at the notorious Trades Hall break-in of 30 September–1 October 1915 in which ‘West’ sought a ballot box and Constable McGrath was shot dead. On that night, Corporal Wren was in Royal Park military barracks as Hardy knew, but he slyly changes Wren’s enlistment date from ‘August’ to ‘Autumn’ to be plausible. Two further homicides are recreated in order to show Wren’s association with the notorious Squizzy Taylor, whose assassination he is alleged ultimately to organise. There is no persuasive evidence of any association except for Wren ordering Taylor off his racecourses. Hugh Anderson’s biography of Taylor, Larrikin Crook (1971), uncovers no contact. But the infamy lingers, just as it does around Wren’s alleged agency in the tragedy of Les Darcy, admirably refuted by the research of the late Darcy Niland, as set out in Ruth Park and Rafe Champion’s Home Before Dark (1995). As Niland said, ‘That story was cooked up later, when certain people were set on blackening Wren’s name’.

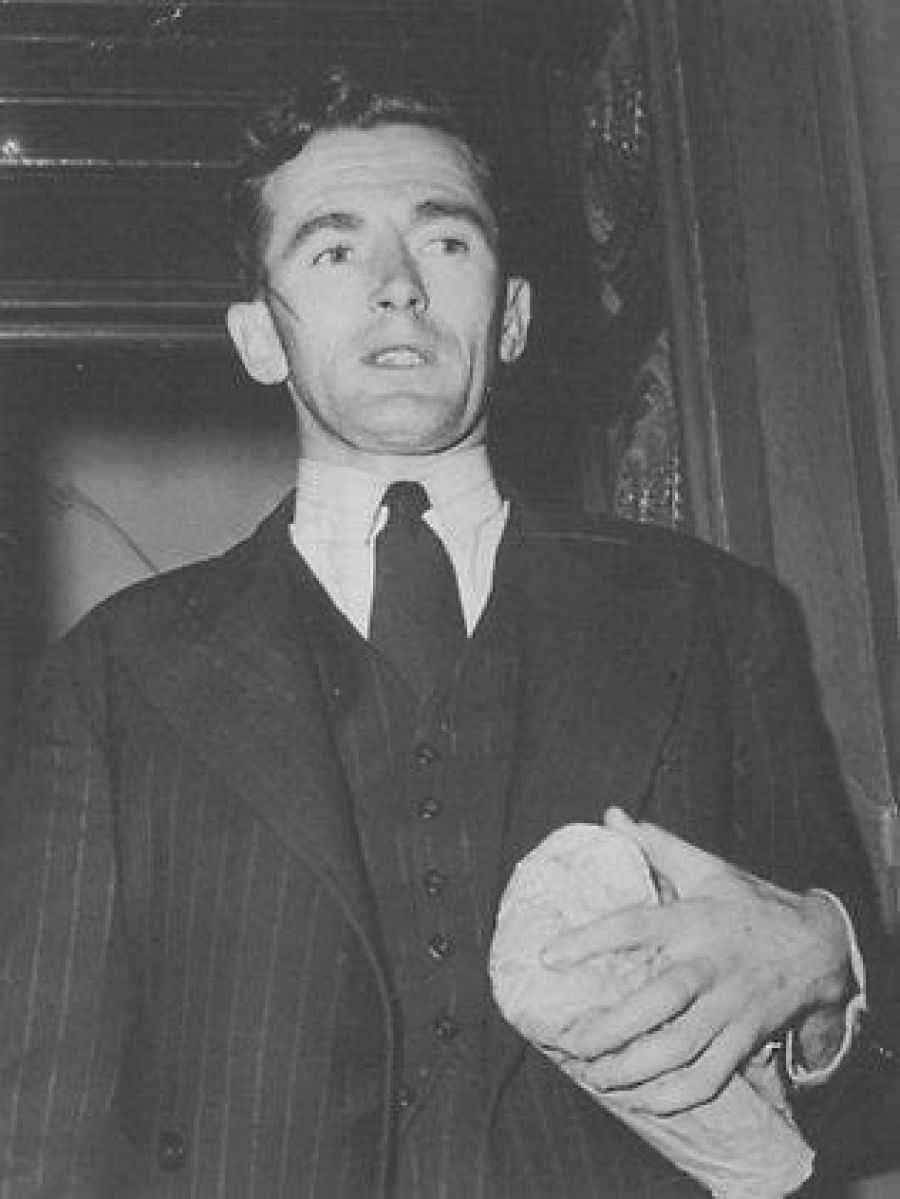

But back to Clark, who gives prominence to Wren and John Norton, the alliterative, dipsomaniacal proprietor of the scurrilous Truth, juxtaposing their photographs on the one page (opposite page 304) with the sanctimonious caption: SEEKERS FOR SALVATION OR PREYERS ON HUMANITY? The juxtaposition of these very different men seems to have made such an impression on Stuart Macintyre, Ernest Scott Professor of History and Dean of Arts at the University of Melbourne, that he believes Wren, not Norton, was the proprietor of Truth. After admitting that in Wren’s case, ‘No one had separated the facts from the legend’, of being seen, on the one hand, as ‘an ogre’ of corruption and, on the other, as ‘an examplar [sic] of Christian generosity’, Clark, in Olympian vein, nevertheless believes him to be:

an Australian version of the American dream: he had risen from the slums of Collingwood to the opulence of Kew by methods which had stained his soul and left him not with the sweet taste of success but the bitter taste of damnation in his mouth.

Clark did not know what was in Wren’s mouth or elsewhere. Clark did not test the possibility that Wren was ‘a seeker after salvation’, but believed that he preyed on humanity because he promoted the bloody sport of boxing, encouraged gambling, made ‘huge sums of money … by roguery’, fixed sporting events, and bribed and blackmailed members of parliament. In view of the popularity of boxing in the first half of the twentieth century with all strata of society, from the denizens of Collingwood to distinguished bruisers like Governor-General Sir William McKell or a proconsul like Sir Hubert Murray (to name two at random) to the manly instructors at greater public schools, it is prim to impugn Wren for running ‘a house of stoush’. In his Lords of the Ring (1980), a discerning Peter Corris provides no evidence of rigged fights. Wrestling was another matter, and had to be if it was to be entertaining, as those who saw the grotesque television display of the Greco-Roman art at the Sydney Olympics would know. Clark, at times, seems very close to those wowsers, ‘straiteners’ and ‘frowners’ like W.H. Judkins who crapulously saw the Tote as ‘a Vesuvius of carnality’. And Wren was renowned in the business world as a man of his word.

As for ‘fixing’ other sporting events, it is droll to see Clark fixing Wren. Grover has no doubt that Wren ‘fixed’ the 1901 Austral Wheel Race by bribing all but the noted ‘Mick Lewis and one or two others’. Reading some newspaper accounts of the day (which Clark did not do), one could believe with them that Bill ‘Plugger’ Martin might have won on his merits, but Clark has to improve on Grover: Wren ‘squared off all the bicycle-riders to allow his man Plugger to win [emphasis mine]’. Of the 1904 Caulfield Cup, an almost impossible race to rig because of the course and the calibre of the field, Clark says that Wren ‘fixed’ all starters, improving mightily on Grover who says that:

the suspicion that Wren ‘squared’ a number [not all] of jockeys … was probably an erroneous rather than a groundless suspicion. The horse personally achieved an honourable success by three lengths.

Clearly, Grover was not a good enough source for Clark; PWG was more reliable. Or he may have had an undisclosed source like the one that told him about Phar Lap’s (mythical) second Melbourne Cup win.

More serious is Grover’s allegation of blackmail of politicians, the most notorious example being the exposure of Chief Secretary Gillott’s financial dealings with Melbourne’s most famous brothel-keeper, Madame Brussells, at a time when legislation to close Wren’s Tote was imminent. Gillott fled to England. Grover’s phrase that ‘the crack of Wren’s intimidating whip echoed along the corridors of the House’ was memorable enough for the Reverend Irving Benson, the noted Wesleyan preacher, to invoke it vindictively at his Pleasant Sunday Afternoon (PSA) following Wren’s death in October 1953. Grover was quite wrong when he said that Wren gave the Brussells information to Judkins who used it first at the PSA and also to Norton for Truth. In fact, Norton used the information first on 30 November 1906, followed by Judkins on 2 December. This riled Norton so much that he accused ‘Jackal’ (‘Jakes’) Judkins of plagiarism on 7 December. Moreover, in the second Lone Hand issue of 1 June 1907, Judkins wrote that not only the police were his informants but that he had done his own research and in any case, everyone around Parliament knew of the scandal. By the time Wren told Labor leader G.W. Prendergast, it was hardly news. Clark lards Grover’s prose:

Some members of the Labor Party, outwardly the purest of the pure, but inwardly ravening wolves in the presence of alcohol or women, cowered in the corridors of Parliament House when a hireling of John Wren whispered what might happen to them if they did not toe the line.

Grover says nothing about Labor MPs ‘cowering’; it was conservative Gillott, but not because of Wren.

In 1928, the former MHR for Dalley, NSW, was accused of trading his seat to E.G. Theodore for £8000. At a royal commission, Wren was alleged to have been the provider through hearsay recounted by two witnesses. The royal commissioner eventually apologised for calling him at all. But Stuart Macintyre believes that there is ‘strong evidence’ that Wren ‘paid several thousand pounds’ to the MHR. His sources do not sustain this. Rather, I believe it most likely that the Labor Party set up an ad hoc fund to which Wren would have contributed, but I have no evidence. The Dean also says Theodore was not ‘short of money after his government had paid £40,000 for the Mungana Mining Company, in which he held an undisclosed interest’. However, this is just a cheap shot. The Dean is guessing again. But there exists a letter from Theodore to Wren at this period asking for a loan of £1000.

Ross McMullin’s centennial history of the Labor Party, The Light on the Hill (1991), contains sixteen separate references to Wren. Only six of them are sourced. Wren is firstly described as:

Short, shrewd and unemotional; his most distinctive feature was his piercing gaze. A variety of shady activities, notably an illegal totalisator brazenly conducted … enabled him to rise from the slums to affluence.

(I hope readers enjoy ‘brazenly’. How should it have been conducted?) Clearly, McMullin does not like Wren, and it is downhill from there. He laments that Frank Anstey, a left-wing hero, accepted money from Wren and ‘seems to have discounted the possibility that donations from Wren could compromise his political ideals’. Quite true, but did they? I have yet to read of Anstey making such compromises or of Wren obliging him to do so. Ian Turner, hardly a right-winger, says of Anstey: ‘A freethinker and a Freemason, he enjoyed the friendship and patronage of John Wren; but he never betrayed his deeply held beliefs.’ Anstey accepted a £500 cheque from George (‘Aspro’) Nicholas for helping him gain a permit for the manufacture of aspirin during World War I. Who complained? What if it had been Wren asking for extra racing dates?

What the ‘embourgeoised’ critics (e.g. Clark, Macintyre) fail to understand among other things are Wren’s Collingwood background and the poverty of the Labor Party. Until 1950, it could not meet the salary of a fulltime secretary; even then it had to be supplemented. The Federal Executive lived on budgets, said L.F. Crisp, ‘which would have shamed an outer-suburban football team’. Until at least the end of World War II, Labor had to rely on meagre membership fees, chook raffles, socials, fêtes or slush funds from breweries, hoteliers and bookmakers, or loans and gifts from mates. Labor MPs tended to lack inherited wealth, even home ownership in some cases; and tenure could be uncertain with challenges from without and within. Labor had not only John Wren but J.J. Liston of the liquor trade, J.P. Jones, and even, as occasion warranted, some businessmen as providers. Conservatives had … do I need to name them? I can safely leave that to Hewett and Macintyre.

This critique is not meant to glorify Wren; he will be dealt with in due course in my biography in as much of his entirety as can be researched. But it is a protest against calumny pretending to be history or fiction, and against gullibility and recycled opinionation. How are we to account for the tribute of Tom Ryan, respected Queensland Premier (1915–19), MHR (1919–21), and tipped, before his death, as a future Labor prime minister? ‘To Australian democracy as a whole,’ he said, ‘Wren was a good friend.’ That same night, 16 November 1920, Hugh Mahon, who had just been expelled from Federal Parliament for ‘sedition’, called him ‘the most strenuous and stalwart friend of democracy and liberty in Australia today’. He was presented with ‘an easy chair, bearing the crest of an open arm with raised scimitar and a lion rampant on a coat of arms’. Quite hyperbolic, of course, but not what could have happened to Al Capone. Still, Wren’s reputation has been such that the late Dennis Murphy, worthy biographer of Tom Ryan, had never heard of this incident and told me in 1982 that Ryan would never have anything to do with Wren. The biographer of James Scullin, John Robertson, says:

It is hard to imagine him finding congenial companionship in John Wren, a shady Roman Catholic entrepreneur who made money through catering for some of mankind’s less exalted pastimes, by arranging boxing matches and running an illegal totalizator.

This is too prissy altogether. Wren and Scullin were well acquainted.

Clark did not live to heed the discovery of a protracted correspondence to Wren from his hero, Dr H.V. Evatt, ‘The man who,’ according to Clark, ‘had the image of Christ in his heart and the teaching of the enlightenment in his mind’. ‘I really need a friend like you,’ wrote Evatt to Wren in 1946. Evatt’s ten letters were made available for his centennial biography which was backed by the Evatt Foundation, but Ken Buckley was not to be nonplussed. He referred to only two of the letters. Evatt was ‘highly respectable’; Wren is ‘unsavoury’. Wren always worked on ‘an exchange of favours’, says Buckley, although what Evatt had to offer him in return for his assistance is never specified. Of course, there is the requisite, gratuitous, sectarian sneer: ‘Wren aimed to buy his way into heaven through his close association with Archbishop Mannix’ (just as, in his recent Concise History of Australia, a curmudgeonly Stuart Macintyre writes out religion and the Irish and puts Caroline Chisholm’s care for young women down merely to a concern with mortal sin). No serious attempt to analyse the Evatt/Wren correspondence was made, although it threw new light on two important men.

Now that Pauline Armstrong’s Frank Hardy has been published, no one should doubt what many of us have always known: PWG was meant to be an assault on the Labor Party and the Catholic Church; and it was planned by the local Communist politburo who found the appropriate literary hoodlum, dishonest researcher and inveterate liar to do it. That does not mean PWG cannot be enjoyed as fiction (if one is undiscriminating) – but it is not history. Dal Stivens managed a much better novel, Jimmy Brockett, based on H.D. (‘Huge Deal’) McIntosh without scurrilously close identifications and silly pseudonyms.

Former Communist Rupert Lockwood has put his finger on one reason for the widespread acceptance of PWG as history: ‘“Irish conspiracies” … Catholic plans for the control in vital fields … substituted in Australia for European antisemitism.’ And its basic impact? Lockwood says:

By concentrating on Irish-Catholics, the Hardy book shielded the real economic owners, the finance manipulators and political rulers of Australia. The interests thus shielded welcomed Power Without Glory.

But one final piece of Wren folklore. On 9 May 1996, at 11.30 a.m. – I knew I would have to record this immediately – I ran into the Dean of Arts in the National Library of Australia. He denied knowledge of his clanger over ‘Wren’s Truth’. A prolific historian, he had obviously forgotten, and countered with a story that recently, at a book launch, Bob Pratt, famous full-forward, had said he had been telephoned by Wren in 1934 and offered £80 to play dead in the Grand Final. I demurred: Collingwood (Wren’s club) did not play in the Grand Final that year. Well, then, whenever, he replied. I said Collingwood did play South Melbourne in 1935, but surely a tycoon would get someone else to offer bribes or, more likely for that sum, it was someone pretending to be Wren. However, there exists a tape of the One Hundred Years of Australian Football television program on which Pratt appeared. It turned out to be Squizzy Taylor, not Wren, to whom Pratt had referred, and the sum was £100. Unfortunately, Squizzy was killed in 1927! As for 1935, Pratt was knocked down by a van at a tram stop in Prahran two days before the Grand Final and did not play. Was Wren, Truth might have asked, ‘prowling in Prahran for Pratt’, riding shotgun to do it in person? Unfortunately, again, the driver turned up soon after at Pratt’s home to apologise with some compensatory cigarettes. He was a South Melbourne supporter.

Obviously anyone such as an historian who hears ‘Wren’ for ‘Squizzy Taylor’ (or reads ‘Wren’ for ‘Norton’) would be well advised to leave Wren and Power Without Glory alone.

Comments powered by CComment