- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Here we have the first intimations of the coming flowering of the Donald Friend diaries, which are to be published by the National Library with support from Morris West’s benefaction. Friendliness was not always the same as ugliness or cleanliness when he was alive. So, it is somehow comforting that two Australian artists, so different from each other in lifestyle, should after their deaths find common cause.

- Book 1 Title: The Genius of Donald Friend

- Book 1 Subtitle: Drawings from the diaries 1942–1989

- Book 1 Biblio: National Library of Australia, $59.95 hb, 144 pp

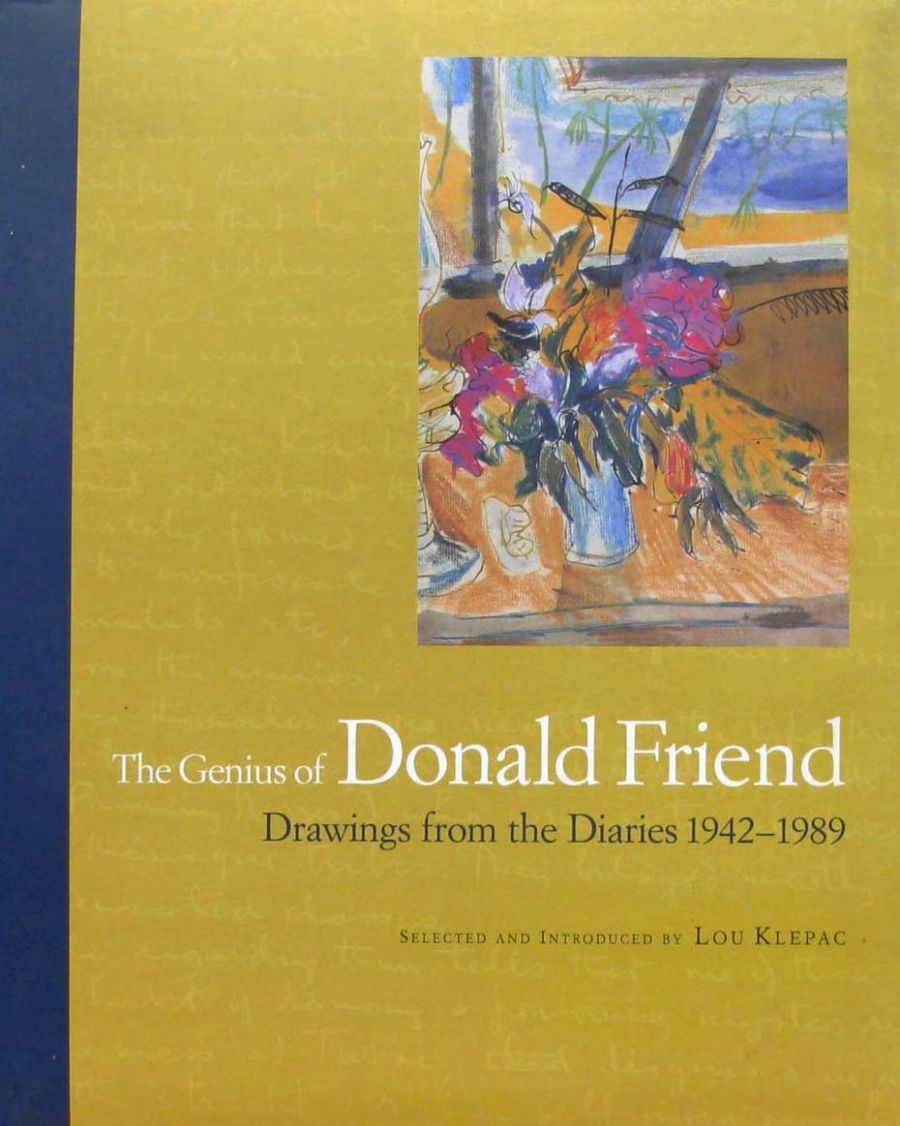

Lou Klepac’s edition of the drawings has been published a year ahead of the diaries. It is a visual and tactile celebration of his friend and client Its sleek ebony cover is gold-lettered, and it has a paper jacket the colour of damp clay, faintly inscribed with Friend’s lefty, slightly backhand script. The spine and margins seem to have been organically dyed from ripe avocado skin. On the cover is a WYWH still life from Magnetic Island. The self-portrait on the back is so in your face it may surprise the young to see it was done in 1944.

Friend’s signature is splashed across the double-title page with calligraphic panache. He uses capital R in ‘Friend’ and the Greek E occasionally, but not consistently – only when he remembers to do so. On page one is the cover of Friend’s last dial)’, a splotchy, primary-coloured still life with a cynical subscript, done with the right hand after a stroke disabled his left, painting arm.

The endpapers are even more poignant. At the front is a black-and-white photograph taken over the artist’s head in 1989, looking down on his worktable. It is neatly set out with pens, ink bottles, paint dishes, a brick to hold down the paper or perhaps to Jean on, a work in progress, a cup of coffee, newspaper classifieds underneath, and friend’s right hand with two watches, cigarette in hand. Slanting across the endpapers at the back is his final diary entry, dated nineteenth December 1988. (He died the following August, without seeing his retrospective at the Art Gallery of New South Wales.) He had only three remaining friends, he wrote. In a barely legible scrawl, with the right hand, he added: ‘Were I God I’d rearrange things so that healthy laughter and wit did not rely for mirth on the spectacle of aged genius fallen in the mire. I’d spare men such as myself the disgraces of indignity and the suffering of suspense.’

Genius? Klepac’s title claims it. Certainly, Friend thought so. But as a lifelong diarist, he did not lack the capacity to face up to his shortcomings. At sixty-eight, re-reading his schoolboy diaries, he wrote:

Self-centred, conceited, atrociously snobbish, frivolous, obsessed with aristocratic delusions, adept at self-deceit. None of that’s changed. Already I was infatuated with the spectacle of myself as a superior being, a genius destined for fame moving wittily around in a world composed of romantic subject matter, arranged for my own delectation.

The G-word again. Robert Hughes early recognised Friend’s drawing talent, and Barry Pearce was always convinced of the quality of his achievement. But the dust-jacket blurb is more restrained, calling Friend ‘one of Australia’s finest draughtsmen’. As an artist dedicated to figurative representation, Friend felt marginalised during the decades when abstraction and colour field and psychedelia succeeded each oilier as the ruling vogues. The tide of neglect turned in the late 1980s, but too late to reassure a depressed Friend that his life’s aspirations had not been derisory.

Klepac, who was Friend’s agent, has written a brief account of the ‘fantastic and charmed life’ that Friend led in the years covered by the diaries: from 1942 when he joined the army, through his friendship with Drysdale and their exploits at Hill End, the periods he spent in Europe, Nigeria, Sri Lanka, and Bali, to 1979 when he returned to Bondi, until1989 when he died in Paddington. This introduces Klepac’s selection of drawings from the diaries, which for years were stored by James Fairfax in a safe at the Sydney Morning Herald. A few have disappeared, but almost all of them are now in the National Library.

The diaries, Klepac asserts, are not mere sketchbooks but contain fully realised works. Yet what are dearly studies in the diaries presage many finished works in the galleries. Klepac’s favourite, a 1984 still life in Paddington that he bought by instalments, appears here opposite a watercolour diary sketch of the same subject. Klepac illuminates how Friend’s early interest in two English illustrators, Thomas Rowlandson in the eighteenth century and Edward Ardizzone in the twentieth, led to his series of diary sketches of guests cavorting on the staircase at Elizabeth Bay House and to his wartime sketches and satires. I would have liked more of this detailed approach applied to his Sri Lanka and Bali periods, or more reasons given for their comparative absence. But for me, two Bondi Junction diary paintings from 1982, a whirling merry-go-round and a mackerel sky, are outstanding.

Drysdale and Friend corresponded constantly during the war. In one letter, Drysdale as good as warns Friend to concentrate harder on being an artist. But what is clear from the diaries – and from Friend’s other writings – is that he was almost equally gifted as a writer. So, it’s a pity that, while several whole diary pages are reproduced in full, others begin and are cut off in mid-sentence, and in some the script is too small to read. Those who take Friend’s genius seriously will now await the publication of the diaries.

Comments powered by CComment