- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Letter collection

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

How good is Shaw Neilson? The question has hung around ever since A.G. Stephens, publishing the poet’s first book, Heart of Spring, in 1919, prefaced it with comparisons to Shakespeare and Blake and declared this unknown to be the ‘first of Australian poets’. The claim provoked competitive jealousies in a possessive, parochial literary world and reviewers responded by insinuating doubts. The question remains: is Neilson the greatest Australian poet? For those who want literature to be a horse race, it is unsatisfactory that there is no declared winner, brandishing medal and loot. Neilson loved horses but he disliked the hold that the sporting mentality had over his fellow Australians – especially men. Yet like most writers he was anxious about his standing and, in his perfectionist’s concern to put his best foot forward, he probably contributed to his readers’ uncertainties. Difficulties with his singularity as a poet were compounded by Neilson’s circumstances, particularly the bad eyesight that made him dependent on others in preparing final versions of his work. That was part of a more general dependency on editors, critics, and supporters who had their own ideas of where they wanted to take him

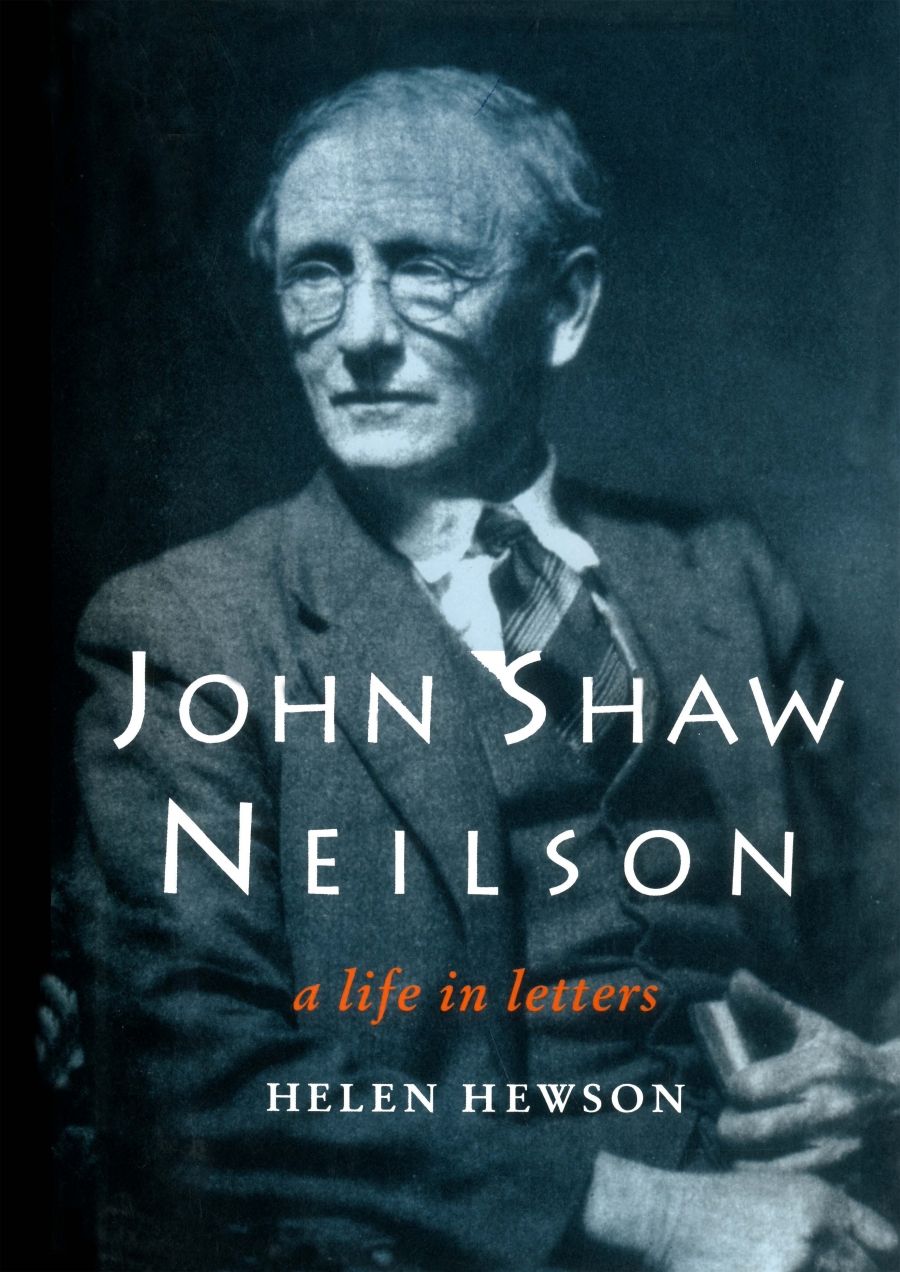

- Book 1 Title: John Shaw Neilson

- Book 1 Subtitle: A life in letters

- Book 1 Biblio: Miegunyah Press $69.95 hb, 503 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/MGGB3

Stephens discovered Neilson and played the crucial role of mentor and sounding board. His praise of the poet may have been premature but, as Neilson knew, the critic was a ‘wizard’ when it came to telling grain from chaff. After Stephens’s death, the baton passed to James Devaney, an ardent advocate who saved much Neilson material and became his first biographer. Among the poet’s early fans were discerning and influential readers such as Mary Gilmore, Nettie Palmer, Percival Serle, and Louise Dyer. Asked for a puff, Chris Brennan adapted Milton's compliment to Shakespeare in L’Allegro, acknowledging the ‘charm of native wood-notes’. Later editors went further afield for comparisons. In his 1965 edition, A.H. Chisholm invoked St Francis of Assisi, the French Symbolists and Rilke. In 1993 Robert Gray, making the contrast with Whitman, nicely concluded that ‘instead of a waterfall, as an origin to our modem poetry, we have in this country [an] ... extremely pure spring’. He follows Judith Wright, who enshrined Neilson at the mysterious heart of her classic Preoccupations in Australian Poetry (1965): ‘The light fell on him unfiltered.’ The dedication Neilson has inspired in his admirers is surely one measure of the poet. As devoted as any, in recent years, in his efforts to keep Neilson in pride of place has been Cliff Hanna, whose studies of the poet culminated in the valuable biographical explorations of Jock: A life story of John Shaw Neilson (1999).

Yet Neilson is far from a household name. In the Great Australian poet stakes, other starters occlude him: Brennan and Wright, Kenneth Slessor, Les Murray. Henry Lawson, and Mary Gilmore are the writers on the money. Have Neilson’s admirers outplayed their hand?

To the elect list of those who have laboured to save Neilson for us must now be added Helen Hewson and the Miegunyah Press. The splendid book they have produced is well titled ‘a life in letters’. It includes ninety-one letters written by Neilson in his own hand, 219 he dictated to different amanuenses, eighty-six letters addressed to him and ninety between other correspondents about him, mostly edited and published for the first time. There are extracts from other sources, including Neilson’s own autobiographical sketches, a compendium of critical responses during his lifetime, a generous who’s who of people appearing in the correspondence, photographs and images, and an introduction that focuses sensitively on sources and influences on the poetry. Light, lively annotation belies the scholarship behind this fine production, which is not only a thing of beauty but as friendly as can be to the user. It lays before us most of the primary material we need – apart from the poems, of course – to get close to this elusive poet.

A double portrait emerges of an inner man who was unwaveringly a poet and an outer man who, for all his privation, sorrow and idiosyncrasy, was equally a poet in his public sense of himself. In one of many letters to Stephens, where he rakes over contractual matters, he explains his long memory for details by saying, ‘I have not much else except my rhymes to think about’. His poetry drew everything else to it. Vance Palmer caught the quality that many people noticed: ‘a queer bird, delicate, sensitive, a little weather-beaten with the rough life he’s led yet with a “peculiar firmness and expressiveness in his nervous horny hands”’. Neilson was at once out of the world and in it.

The portrait will always have its gaps, as Hanna’s biography admitted, for reasons partly of happenstance but also related to Neilson’s own concealments. Books and papers were eaten in the mice plague at Chinkapook in 1917, while other documents were left behind by the canny poet in the course of a wandering life. The earliest letter in the book dates from 1906, when Neilson was already in his mid-thirties, ten years after his first poem had been published in the Bulletin. His own readiness to discard his literary remains added to the ‘cold neglect’ with which the world by and large treated him. His texts, as we have them, are not all definitive and there can be a suggestion of something lost or unfinished that continues into his reputation’s struggle with posterity today. John Shaw Neilson: A Life in Letters recovers all it can and works tactfully around the gaps. It should ideally be followed by a complete variorum edition of the poems in chronological order – not a task to be undertaken lightly.

As it is, the letters make certain things clear. Neilson always aimed high: his modesty was a kind of discipline. He was an astute critic of other people’s work, and a good judge of his own. The dozen letters between Neilson and Stephens as ‘Song for a Honeymoon’ evolves are a revelation of creative (sometimes destructive) tensions at work. Neilson looked for a quality he called ‘music’, echoing Verlaine (in Nettie Palmer’s translation). He found it in old songs and hymns, like ‘Waly, Waly’ and ‘Abide with Me’, in the Book of Ecclesiastes, in Shakespeare's songs, in Keats and Stephen Foster. His music was a form of concentrated, almost surreal, imaginative apprehension, and he was its final arbiter. The music in other popular poets of the day – Shelley, Tennyson, Whitman, Kipling, Masefield – was wrong. He called it ‘booming’, showing his distrust of any sort of national laureate role. (He disliked Wagner.) Neilson was a modern in rejecting Victorian cant and Edwardian bombast, but his more original (radically Australian?) solution was to jump back over the imperially inherited conventions of Literature that saddled other contemporary writers in order to touch the pre-modern springs of lyric poetry.

Neilson called himself a singer. He took as much care to get every word right as Irving Berlin must have done when writing ‘Always’. In an era when sheet music was the equivalent of today’s Napster downloads, he was keen to see his lyrics set to music. Through Louise Dyer’s introduction it might have happened with Gustav Holst, but that was another hope that fell by the wayside. In one letter Neilson tells Devaney how his poems came to him. The connection with music is intimate and bodily:

Sunlight & nothing particular to bother one help the urge … Riding along slowly on a quiet back I would try to bum the tunes I knew. I would become dissatisfied with these. I would try to hum tunes of my own. This vanity I believe has been a great help to me. In a quarter of an hour or so I would find out that I was quite powerless to compose a tune of my own. Then as a sort of consolation to my wounded pride I would start to make a rhyme.

The rhythm of song, and of the horse’s movement and the natural world, and some abandonment of ego, combine in slow creativity. Elsewhere, Devaney describes taking dictation from the poet in old age:

He would sit with his eyes closed, his lips moving as they shaped silent words, his head sometimes shaking as though he were rejecting words or phrases. But sometimes when he had found the words he would look up with a strange intentness. Then he had a beautiful direct look …

There is something shamanistic about this, suggesting connections with deep oral and folk lore. In another letter, Neilson compares his ‘rhyming ability’ to a ‘holiday horse’ that he would like to pass on ‘to some young fellow possessing plenty of vigour to carry on’. His gift belongs not to himself but impersonally to a vital line of transmission. I am reminded here of Walter Benjamin's storyteller who ‘takes what he tells from experience … [and] in turn makes it the experience of those who are listening … Not only a man’s knowledge or wisdom, but above all his real life – and this is the stuff that stories are made of – first assumes transmissible form at the moment of his death ... it is natural history to which his stories refer back.’ That is what tradition means. In the premature loss of those closest to him – baby brother, mother, sisters – the moment of death loomed early in Neilson’s life, shaping and, in Benjamin's sense, authorising the natural history he transmitted. The first poems are each about death; his best-known asks that his song be ‘delicate’ in order to live where ‘death is abroad.

Delicacy was the sly force with which he countered the crude noise of jingoism and slip-rail all around him. He was ‘delicate’ about his diction, intent on getting it right. In one exchange with Stephens he writes: ‘I know pretty well how men and women on the land express things. One has to dodge too much of the old conventional Ballad speech but must avoid the other extreme ...’ His reference is the oral world of a tribe. A teenage girl he met in Brisbane in old age recalled: ‘The Irish use a flowery sort of speech, and that’s the way he used to talk. It was certainly not of our culture.’ That verbal attunement to distant sources marks a deeper craftmanship, as Mary Gilmore saw: ‘There is a scholar in you & a scholarship, not in the rest of us. It is the want of scholarship that is the curse of Australian writing & leaves us all temporary. Scholarship is not in references but in matured and controlled thought’.

John Shaw Neilson: A life in letters puts to rest the debate about where the humble Mallee boy got it all from. It's clear he could have got it from anywhere: what matters is what he did with it. Early twentieth-century Australia was eager for a national culture, yet, despite a few sophisticates and visionaries, was weighed down by social conservatism and uncertain where to look. Against that background, Neilson's reminders, in so many letters, of an older, tougher reality are more stirring than the literary names he drops:

In ‘26 when I was working at the Iron Ore Quarry at Cadia in N.S.W. had for a mate an old bushman. He was seventy-two years of age. He told me that became from Tasmania to the Bathurst district. He was then a lad of twelve. He said that he could remember a squatter giving a letter to a convict to go to Bathurst Gaol to get a flogging. The convict walked all day on a wet day to do this. This would be about ‘66. I had no idea floggings existed so long.

The story inspired a ballad that Neilson worried about publishing: ‘The main trouble is that many people would misunderstand this and think that I am a red-ragger.’ He had strong political views, but was reticent about them, as about other things we nowadays want to know: sex, transgression and insanity. What are we to make, in this era of paedophile hotlines, of a fifty-year-old bachelor who writes: ‘I am again trying a girl say about sixteen a momentous creature’? Why does he urge a young rhyming comrade to read Otto Weininger’s Sex and Character, a theory of psychological types that justifies misogyny and anti-Semitism? This scary book influenced Wittgenstein and when Weininger, Jewish and homosexual, shot himself he was remembered by Hitler as ‘one good Jew’ who killed himself out of self-disgust.

Some of Neilson’s comments seem to make wild gestures towards our own hybrid present. ‘my eyes are no good for a couple of days yet,’ he writes in 1938.

I strained them badly yesterday looking at Albert Namatjira’s water colour. I think is it a wonderful show. The tree trunks seem very like the real thing and the skies & hills remind me of Japanese prints. It is possible that our blacks may be very distant cousins of some of the Japanese.

It is easy to feel sorry for Neilson, but the letters – cagey, courtly, argumentative, luminous – affirm his determination and his freedom. ‘Are you still at the Pharmacy,’ he asks Victor Kennedy after recommending Weininger.

Don't you think a bit of knocking about would do you good. Say a season in (a) shearing shed, or at a grape-picking and harvesting ... I think a bit of roving does a young fellow good.

Neilson's own hard roving was the shell that protected the delicate truth of his art. For most of last century, poetry and criticism moved in different directions from Neilson’s. We still don't really know how to talk about him – not as suggestively as Hubert Church, deaf New Zealand émigré, could when he wrote in 1921:

Many times I hear in Neilson’s music the chords of the great dead. Not for imitation; there is none of it. True poets are in a rich confraternity, like roses on a tree. There are better and best; all have the music of devotion, which centres in the troubled heart and finds its impulse in solitary deeps.

Yet perhaps we come to speak of Australia in new, multiple ways – an environment haunted by the death but capable of stubborn, delicate resistance; a culture of transmission from deeply old to harmonically new – we may come to connect differently with this remarkable figure. Until then, what Hugh McCrae said back in 1955 must stand: ‘Shaw Neilson reigns forever amoung the stars – unreachable.’

Comments powered by CComment