- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

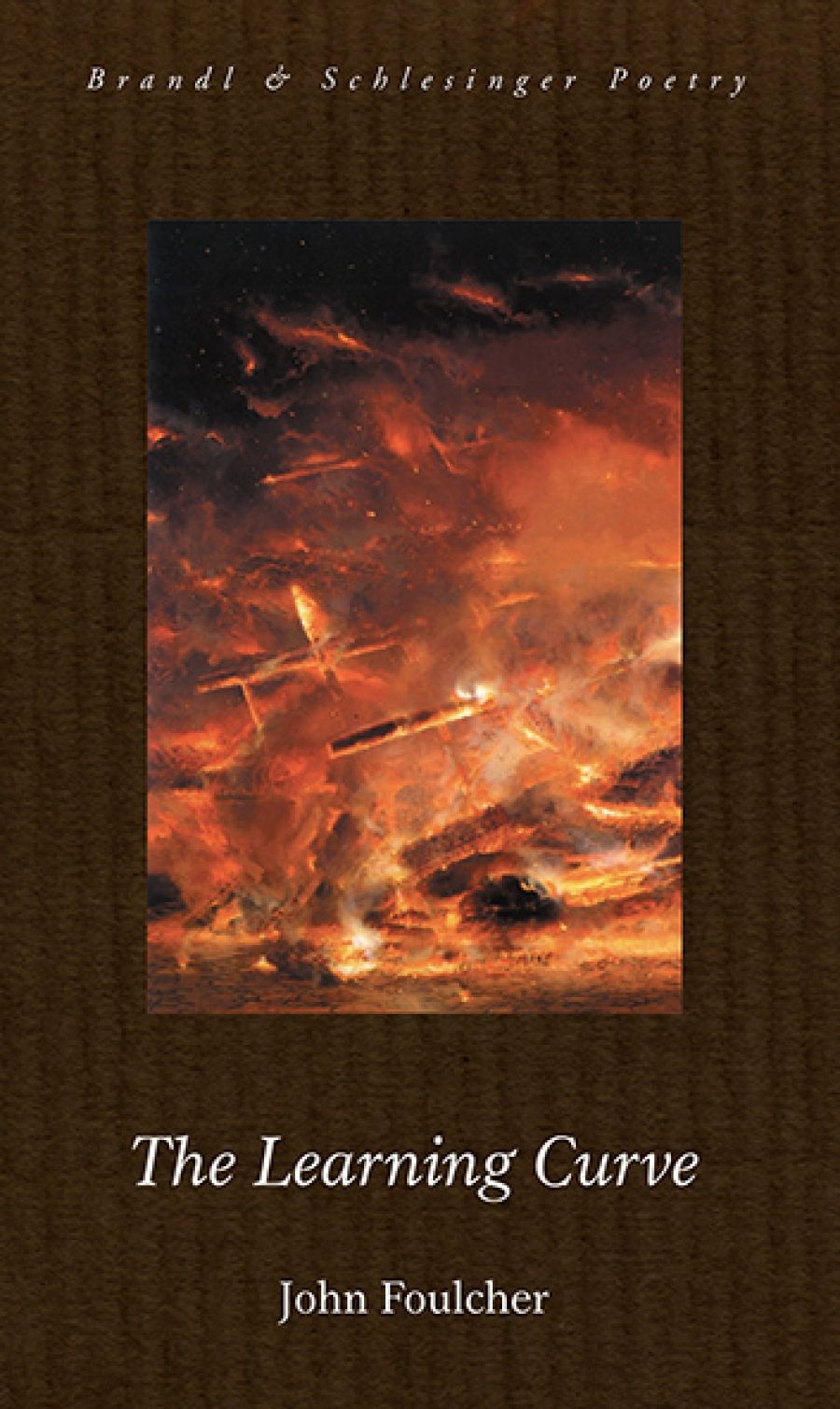

- Article Title: School of Hard Knocks

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

John Foulcher’s The Learning Curve is a sequence of poems set in a fictional school called Saint Joseph’s. The ancient chestnut in which a mother’s attempts to get her son off to school are met with a lot of sulking about the pointlessness of the work and the nastiness of the children – to which she responds that as the school’s headmaster he really has to go – feels peculiarly appropriate: neither the students nor the teachers particularly want to be there. Using mainly dramatic monologues, Foulcher paints a depressing picture of a school where professional disappointments, an inept and religion-infested staff, and a general air of mutual loathing combine to produce what amounts to a psychological tragedy (with some physical tragedies thrown in for good measure). Sometimes it’s as if Joyce Grenfell’s scripts tenderly mocking English schoolmistresses have been violently revised by a Writer in Residence at the proverbial School of Hard Knocks.

Masturbation, girls. Don’t blush,

Edwina, we need to be direct

when dealing with the facts of life.

There will be some temptation

for girls who do not share a room –

God loves the sinner, hates the sin,

just remember this. Masturbation.

(‘Sister Lucy’s Sex Education Class’)

In ‘Another English Test’, students are asked to read a poem and ‘write an essay discussing its value’. One of the things to which they are required to make particular reference happens to be ‘register’, perhaps suggesting some wry anticipation on the poet’s part of the way in which The Learning Curve itself will be evaluated. Such a reliance on dramatic monologue does, indeed, invite a judgment as to the distinctiveness and believability of individual voices. Unfortunately, in this respect, the book is found to be wanting. So bleak is Foulcher’s outlook that the idiosyncrasies by which we come to believe in a character are lost to the overall atmosphere of resentment and stupidity (‘we’re all fuckin’ sick and fuckin’ tired’; ‘Sometimes it’s good, a death in a school’). Indeed, the reader will come to feel that many of the ‘characters’ merely reflect the poet’s own rage, or the poet’s own position (that the only couple of Nice Guys happen to hail from Humanities – from the Art and Drama departments – may add to this impression). Robert Gray’s assertion, quoted on the book’s back cover, that Foulcher’s collection has captured ‘the authentic backstage smell of a secondary school’ is wide of the mark to say the least.

Like The Learning Curve, Graeme Hetherington’s Life Given (Indigo, $18 pb, 86 pp) is effectively a sequence and deals at length with the traumas of childhood. Unlike The Learning Curve, however, Life Given gives it to the reader straight, in traditional lyric form. So explicit, indeed, is Hetherington about his own unpleasant childhood and general state of mind that a reference to ‘confessional’ poetry is almost unavoidable. Since public self-examination tends to be labelled as indecent exposure, confessional poetry will be successful only if the poet can convince his readers that his personal pain has impersonal resonance. Thus, Hetherington attempts to link his traumatic Tasmanian childhood with Tasmania’s bloody convict past. Much of the action – mental and physical – centres on Hell’s Gates, which allows the poet to jump rather easily from one theme to the other (Hell’s Gates, of course, denoting both the perilous entrance to Macquarie Harbour through which the convicts would have passed and Hetherington’s own, purgatorial state, the ‘rot of guilt’ and suffering). Here is a typical passage, from ‘West Coast, Tasmania’:

Hell’s Gates, where convicts knelt to fuck

Each other and for prayers before

Their nightly or eternal rest

From knotted rope or blow behind

That they might then be eaten raw,

Supplied my past, and C of E

Boys’ boarding school, housemaster cruel,

Dickensian, was living proof.

This, surely, is too big a jump. Of course, the past affects us in ways that may indeed be detrimental, even catastrophic. But to say that there is a concrete link between the treatment of British convicts and one’s experience of boarding school – to say, as in a later poem Hetherington actually does, ‘The past’s worked itself out in me’ – suggests an implausible level of insight, or else an overdeveloped sense of one’s own victim status. At one point, Hetherington employs the image, ‘My shadow drowned, lost like the blacks’. To which those ‘blacks’ who were not lost might respond that this is just a friendlier form of cultural usurpation.

The above quotation also demonstrates Hetherington’s peculiar style. ‘Their nightly or eternal rest / From knotted rope or blow behind’ seems pointlessly oblique. What the poet is hinting at is clear; why he is hinting is less so. Syntactical disruptions like ‘housemaster cruel’ seem pointless, too. These stylistic oddities, though, are far from pointless: they are there to fill out the form – the unrhymed, iambic tetrameter to which the poet commits himself for the larger part of this book, and for which, as his contortions suggest, he lacks the requisite skill.

After reading John Foulcher and Graeme Hetherington, both of whose books are profoundly dark, I found myself in sympathy – though certainly not in agreement – with the eponymous ‘He’ in Michael Sharkey’s ‘Look, He Said’:

… he told me that there wasn’t any future

writing up domestic stuff,

since everybody knows life’s tough for other people:

that’s not art:

poetry must liberate us from the world and sleaze;

our mission statement’s how to live inside our heads

with language,

see what beauty we can find.

Since some great poets of ‘the world and sleaze’ have been poets of exceptional beauty too (Yeats and Auden come to mind), this is a largely false dichotomy. And while Michael Sharkey is surely right to keep the poet here at arm’s length (signing off, ‘I said, good luck’), the view that poems concerned with the seamier side of life will tend to be unbeautiful is a recipe for sloppy writing.

Many of the poems in History: Selected Poems 1978–2000 (Five Islands Press, $19.95 pb, 110 pp) would, I think, have benefited from a bit of smartening up. The title poem, for example – a meditation on Australian history sparked by seeing a pretty girl in ‘a jacket that comes from a sheep’ (which is to say, a sheepskin jacket) – is written in a rather featureless style that, though it may reflect the poet’s enervation (‘When I get off / I have lived here for 200 years’), is far from being a pleasure to read. This is a shame, because Sharkey can write attractively. His best poems are those about love, which have a distracted, outsiderish quality. From ‘Poem for Translation into Any Other Tongue’: ‘How can I talk freely of your breasts? / Hot avocados. // What I like about your neck / is your head on it, / laughing.’ I also liked ‘Without You’, with its easeful lines of one to three stresses, each of its four short stanzas pegged with one, otherwise random rhyme (‘without you / all music /would be late quartets and blues: / there’d be no news / to fuel poems: / paintings would hang down / their heads in shame’). Generally, though, I found this a disappointing book.

Comments powered by CComment