- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Suffering in a Golden Age

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Eugenia Williams’s appealing memoir of a Czech–Hungarian family spans many defining moments of twentieth-century European history. In the final days of World War II, the author and her family were part of the civilian population trapped between retreating and advancing armies. The memoir concludes more than two decades later. In 1969, one year after the Czechoslovakian democracy movement was crushed by the Russians, the family joined a refugee exodus to Austria, and eventually received immigrant permits to Australia. Williams appears to have been cushioned from trauma by her nurturing family and community. The bright surface of the narrative also reflects her buoyant temperament.

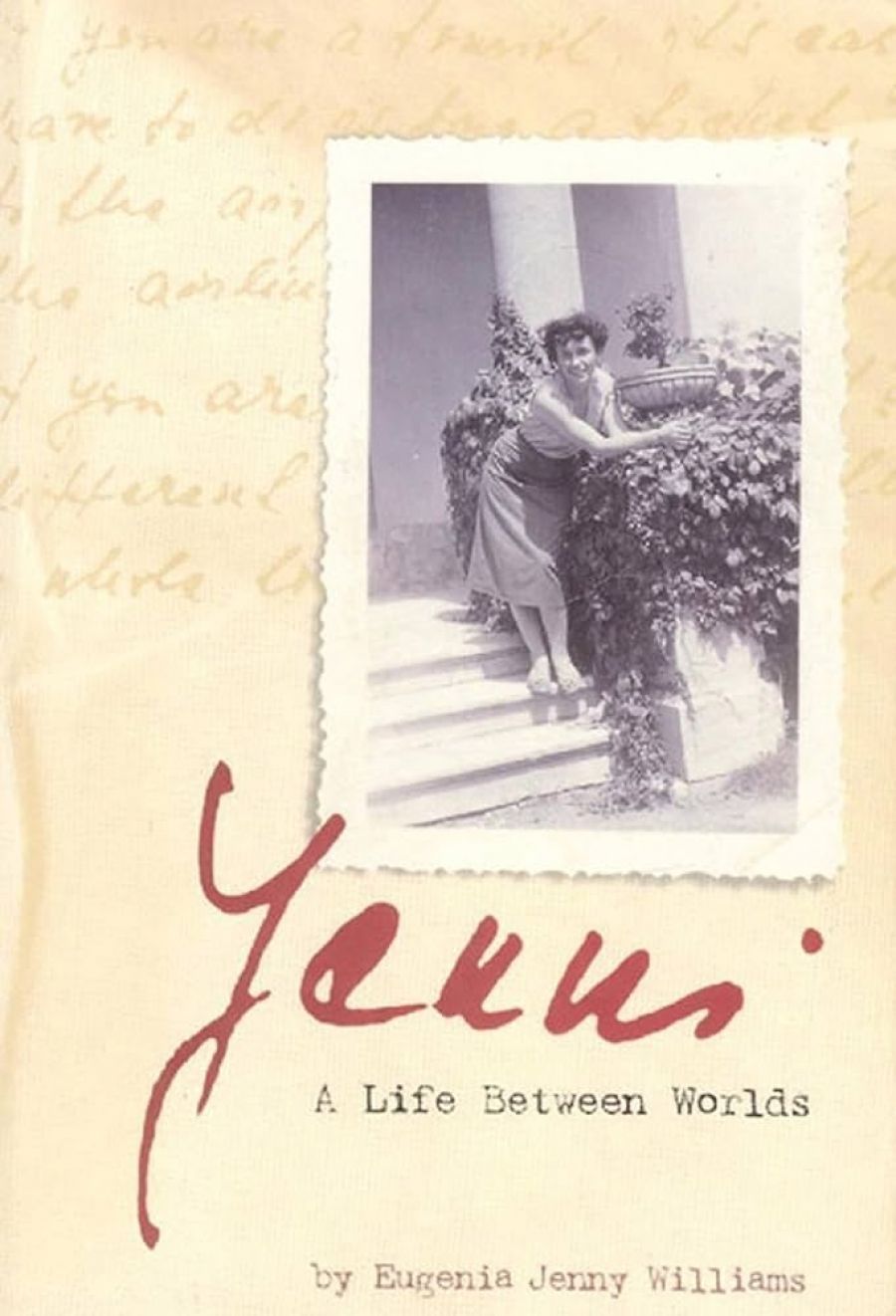

- Book 1 Title: Yenni

- Book 1 Subtitle: A Life Between Worlds

- Book 1 Biblio: Pluto Press, $29.95 pb, 342 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Yenni: A Life Between Worlds begins with vivid snapshots of childhood. Yenni is alone in a cart with a runaway horse. Woken by aerial bombardment, Yenni’s family sprint down the street to a freezing cellar. Her grandparents make mysterious trips up a ladder to a manhole in the toilet ceiling. Out of nowhere, foreign soldiers appear pointing guns. Without an adult frame of reference, it is all strange and wonderful. With remarkable facility, Williams re-creates the emotional and physical textures of events from early childhood, through her strong-willed and adventurous adolescence, to adulthood. However, as a narrative strategy, the ‘knee-high’ innocent gaze is a trifle overworked. The autobiographical element is not as captivating as her occasional gems of social observation.

Williams grew up in a relatively privileged, middle-class, Hungarian-speaking home in Slovakia. The early loss of her father, housing shortages and the necessity for women to work had paradoxical benefits. Children enjoyed the nurturing of three or four generations in shared households. In the ethnically-mixed border regions of Hungary and Slovakia, communism coexisted with a resilient village and small-town culture. A deep-rooted black economy was based on networks of family, friends and community. The black economy, the backdoor version of free enterprise, may have prevented the unpopular régimes of Eastern Europe from imploding much earlier. But Williams has no political axe to grind. Learning how it worked was just part of growing up, becoming streetwise.

Williams’s energetic endeavours to get a two-room flat entailed a visit to Comrade Babchakova’s crystal-filled apartment. The comrade, who distributed housing permits, was a divorcée supporting her elderly mother and son’s university studies with the proceeds. She told Williams she did not want any more crystal. For my money, Williams’s DIY bribery and corruption tips produce the funniest and most memorable writing in the book. Shrewd and non-judgmental, her observations are reminiscent of many great Czech satirical films.

Williams’s political awakening was delayed until the Prague Spring, the political movement for reform that precipitated the Russian invasion. ‘By the second half of 1967 everyone felt the unease, even people like me, politically naïve and optimistic.’ Although Williams characterises herself as politically naïve, it would be more accurate to describe her as conditioned by a national ethic of pragmatism. Her priorities were personal and domestic: getting better housing; managing her job, her children, her budget; and occasional holidays with her wayward husband. Scarcity enhanced the value of commodities Westerners take for granted. By the time she left, Williams had an impressive repertoire of contacts and survival strategies. Her drive and resourcefulness incidentally illustrate the classic Darwinian explanation for immigrant success.

Despite the crackdown after the Prague Spring, Williams never felt in any personal danger. Nowadays, she would be classified as an economic migrant gambling on a better life. After their daring escape to Vienna, she and her family were stuck in the proverbial queue, putting their lives on hold, while their savings dwindled. Waiting was more demoralising than fear. But the uncertainty that tormented them was whether they had made the right decision, and how soon, not if, they would get their immigration permits. She suffered her share of humiliation but, in comparison to the lot of refugees today, she is describing a lost golden age.

As a character, Yenni/Eugenia appears to step straight out of the brilliant tradition of Czech political satire. Her social conformity and robust pursuit of material goals reflect traditional Czech pragmatism, reinforced by powerful feminine nurturing instincts. But the ordinariness of Eugenia Williams’s story is double-edged. An affirmation of humanity in difficult times, her confessions about her love life, or lack of it, her husband’s unfaithfulness, her interest in nice furniture, clothes and recipes also verge on banality.

Williams’s diffidence about her English is quite unjustified, but the writing is sometimes flat and repetitive. Occasional lapses of syntax and punctuation are attributable only to poor editing. It is hard to believe anyone whose native language was not English could have written: ‘I desperately want to repair the situation between Yirka and I’; or this sentence: ‘The household expenses were shared between her and our grandparents, we had no financial problems.’ Overall, more could have been done editorially to shape this work and tease out its self-understanding.

Yenni is a valuable contribution to the growing genre of migrant literature. Its human interest is inseparable from its complex historical and political background.

Comments powered by CComment