- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Winning Stories in the Kimberley

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Ian Crawford’s title announces his book’s challenge: to provide a view of Kimberley history that builds on the foundations of Aboriginal oral tradition. The title is taken from Aboriginal storyteller Sam Woolagoodjah’s account of the first pastoral settlement of the Kimberley in the early 1860s.

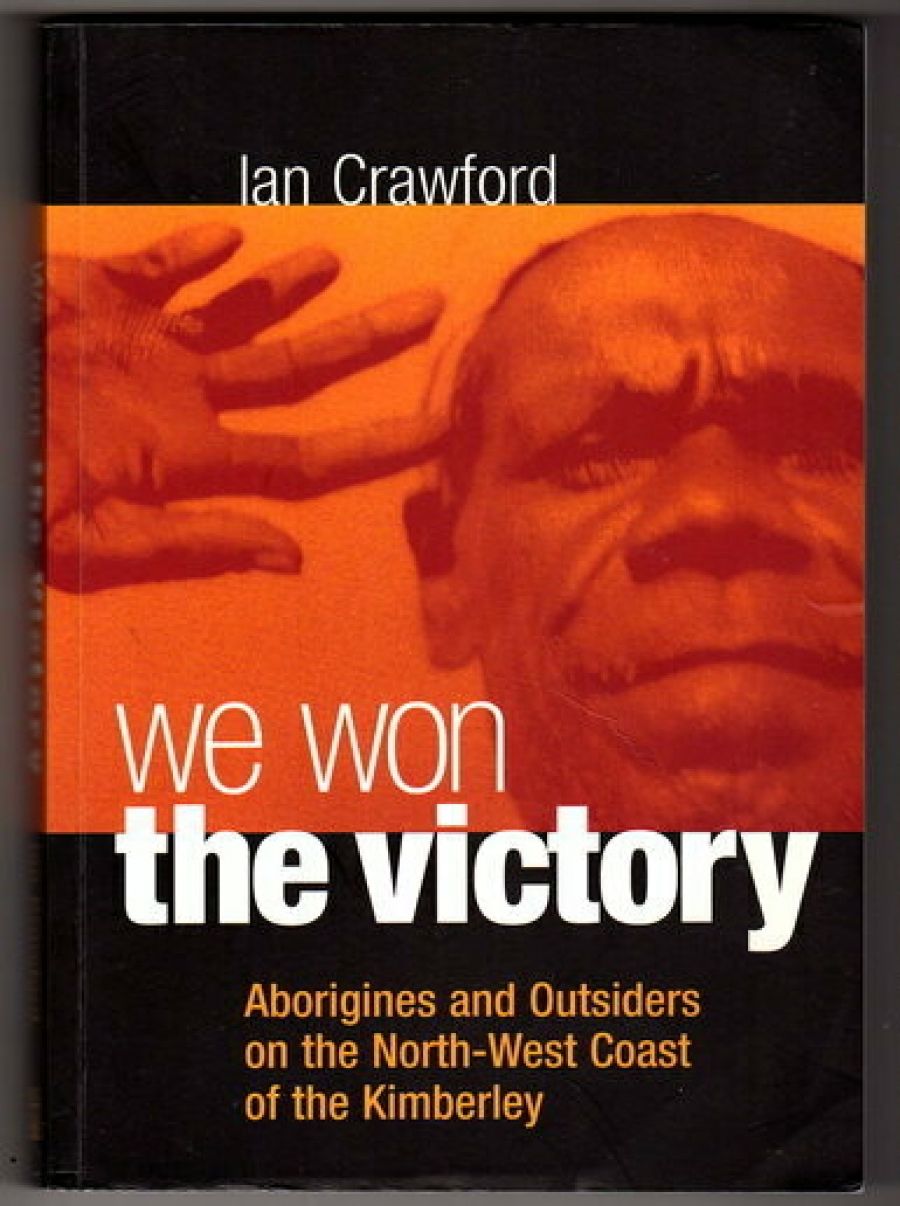

- Book 1 Title: We Won the Victory

- Book 1 Subtitle: Aborigines and Outsiders on the North-West Coast of the Kimberley

- Book 1 Biblio: FACP, $24.95 pb, 336 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

The events that led the settlers to abandon the Kimberley after just a few years are only sketched here. Crawford opts instead for the short version of the story given by Aboriginal people, which credits their ancestors with ‘getting rid’ of the first pastoralists; in other words, ‘We won the victory’. The ‘victory’ was hollow and its details are missing, but by the end of this book we know that the title is also a reference to the irony and ambivalence felt by Aboriginal storytellers towards Europeans.

Crawford’s tapping of dialogues, attitudes, motivations and experiences from over a hundred years ago is a fascinating exercise that leads to intriguing scenarios. He admits that some of the accounts of events in this region are pieced together from scant documentary sources. Some are based on just a few words in diaries, stories or songs, then linked precariously with paintings or maps or fragments from old campsites. Such is the nature of the historical traces from this remote region of Australia where a ragbag of characters lived in daily contact with Aboriginal people on this rugged coastline. As Crawford points out, it was these types that shaped many Aboriginal people’s views of white society. They were also the earliest settlers of northern Australia.

Crawford draws on taped narratives and songs from men and women of the far north Kimberley coast for his exploration of relationships between the indigenous occupants and the many visitors who came in contact with their country over a period of nearly two hundred years. These stories are integrated with Crawford’s own archaeological research and observations, as well as recollections of conversations that span almost forty years from his initial fieldwork in the north Kimberley in the early 1960s. Crawford’s account of Father Sanz at Kulumburu Mission is based on his recollections of a conversation with Sanz in about 1973. Father Sanz is described as disillusioned with his task since he could only influence about two hundred Aboriginal souls. He was contemplating a move to South America where his flock might contain two thousand people. According to Crawford, Sanz commented that there were further frustrations in the north of Australia where he had only just managed to ‘kick’ people inside the door of heaven where they would probably remain until his own time came.

The author positions himself alongside Aboriginal people, often working as a scribe and interpreter. He is conscious of the problems of calling aloud the names of deceased Aboriginal men and women, and provides a footnote trail of permissions to use someone’s name.

Some texts are transcribed from tapes of conversations, interviews, songs and ceremonies. Albert Barunga’s explanation of rain is an example of the poetic turn of phrase that Crawford occasionally captures in his faithful rendering of taped narratives: ‘[When] the earth is hot … it breathes: the earth, it breathes, it is alive. When it breathes, it’s a steam go up, and it gives cloud to give rain.’ Characters full of humour emerge from the transcribed oral historical texts. Jack Karadada’s ‘Um’ story is a high point of creative storytelling. He describes Aboriginal men from different language groups engaging in a dialogue of meaningful hand signals and ‘umms’. This style of storytelling takes non-Aboriginal readers into an unfamiliar world of oral history and dramatic re-enactments of conversations from long ago.

Such reporting provides an intimate perspective on relationships developed over many years between a multinational group of missionaries, pearlers, beachcombers, farmers and Aboriginal people. This triangulation of documentary record, physical objects found on various archaeological field trips, and the oral tradition comes together to enhance the understanding of events in this remote area.

Some already documented are enlarged, such as first-hand observations of the bombing of the northern coast by the Japanese during World War II; others are significantly reinterpreted. Crawford comes into his own with the discussion of Macassan visitors to the Kimberley coast and the cultural and material exchanges that occurred between them and indigenous people over hundreds of years of contact.

The book’s literary strengths can also lead to absences. Crawford does not engage with current academic debates nor review the full range of written historical documents or secondary texts that might touch on events and relationships mentioned in his book. In my view, he doesn’t need to; that would be another book.

Comments powered by CComment