- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Custom Article Title: Pompey at Half Mast

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Pompey at Half Mast

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In September 1929 John Monash, ex-commander of the Australian Corps in France, sat down to reply to his former subordinate, Harold ‘Pompey’ Elliott, a National Party senator and militia major-general. Elliott had asked why he had been passed over for a division in 1918. What ‘secret offence’ had he committed that General Birdwood, the English chief of Australian forces, had denied him advancement? Monash was disturbed that Elliott’s sense of injury should be so raw a decade after the guns had fallen silent. In a tactful, compassionate reply, he set aside the idea of a secret offence and gently reminded Elliott that others, too, had had complaints, and had left them behind. The affection of their men mattered more than honours: ‘This same affection and confidence you have enjoyed in rich measure, and no one can question that it was well deserved. After all, you commanded a celebrated Brigade during the period of its greatest successes … Then why worry as to the verdict of posterity upon so brilliant and soldierly a career?’

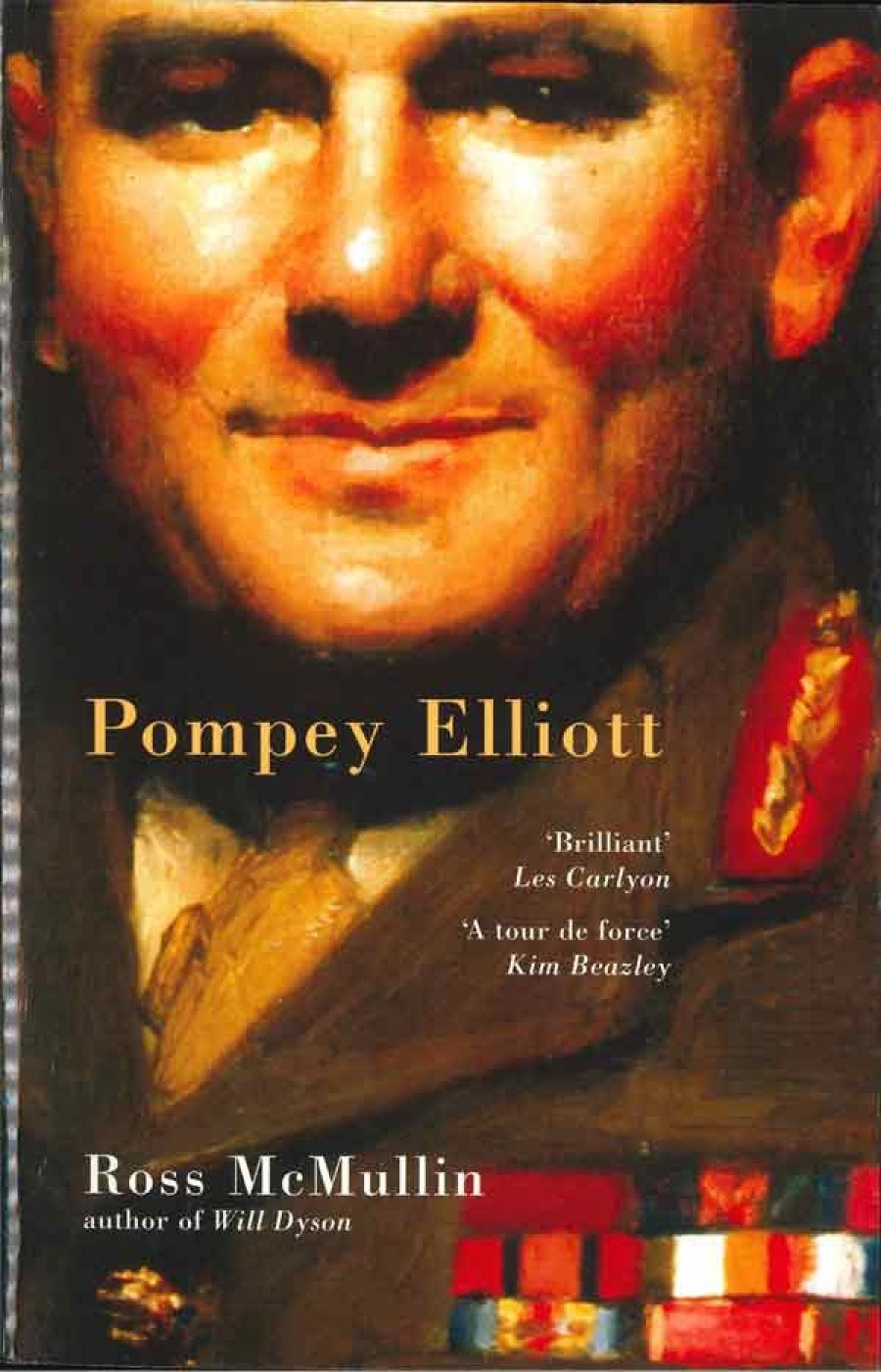

- Book 1 Title: Pompey Elliott

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribe, $45 pb, 732 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Ross McMullin argues rightly that an Australian who achieved so much ‘deserves to be better remembered’. His vivid, thorough biography is the first full account of Elliott’s life – surprising, given Pompey’s eminence, popularity and personality. McMullin takes the opportunity to reappraise events and people, to weigh Elliott’s career and to seek an answer to the question that consumed him: given his achievements, was he treated unjustly? McMullin thinks so, and blames Birdwood and his right-hand man, Brudenell White. Not all readers will be convinced, however much they admire the heroic figure McMullin creates.

Elliott’s family lived frugally by farming close to Charlton until his father struck gold near Coolgardie in 1894. Harold went to Ormond College, studied law and indulged his interest in military affairs. Two tours to the Boer War brought him a DCM and a reputation as a skilful leader and tactician. He was christened ‘Pompey’ – after a footballer rather than the Roman general. By 1914 Lieutenant-Colonel Elliott was commanding the 7th Battalion, a Victorian unit he led ashore on the first day at Gallipoli. He was often where the action was hottest, living up to his article of faith: ‘No officer should order his men to go where he is afraid to go himself.’ Yet his inspired leadership did not bring a decoration. Not for the last time he felt overlooked. Instead he was given the 15th Brigade, a command he held through the war. He identified heart and soul with his ‘boys’ and led them through some of the worst fighting on the Western Front. He met the returning survivors of the Fromelles disaster with tears streaming down his cheeks. He led them to victory, too, at Polygon Wood, Villers-Bretonneux and Peronne. The army was regaled with Pompey stories: shot in the buttocks near Amiens, he directed the fight with his trousers at half mast while medics tended the wound. He also spoke his mind, criticised superiors, dissected their flawed tactics, berated British staff officers and threatened to shoot deserters. When the Armistice came, the 15th paraded spontaneously to give its brigadier three cheers. But he didn’t get a division.

It is easy to probe the book’s soft spots. Tighter writing, fewer tautologies and repetitions, and a few more good maps would have helped. Occasionally, I would have welcomed a cooler tone: Elliott was big enough not to need superlatives. McMullin charts Elliott’s shifting states of mind but seldom plumbs his psychological depths. But the strong points hold. A powerful portrait emerges from McMullin’s prodigious research, which included interviews with Pompey’s ‘boys’. He is good at teasing out intrigues at the top and at postwar manoeuvres to gain the high ground in official accounts.

The biography emphasises what all concede: that Elliott was a masterly tactician and an outstanding commander on and off the field. Why then was he passed over? McMullin does not disguise Elliott’s explosive character or his capacity to take unreasoning offence. Brudenell White told Elliott in 1918 that no one doubted his courage or ability, but added, ‘you mar it by not keeping your judgement under complete control’. McMullin records enough bizarre incidents to support that view, among them an extraordinary public squabble with a brother officer over a couple of social functions in Melbourne.

Perhaps no commander was so loved by his men or gave so much of himself in return. Years later, Elliott still remembered every private soldier who had served with him. Doubtless he also remembered those who, like his brother, remained somewhere on the Western Front. ‘One might wish to have died with them,’ he wrote shortly before he sailed for home in 1919, feeling, as so many did, that his best years were behind him. Elliott’s story – the great-hearted captain broken by life’s blows – is a tragedy of Shakespearean dimensions, and our history is the richer for McMullin’s telling of it.

Comments powered by CComment