- Free Article: No

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Rather Different Poets

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Since 1982, Robyn Rowland has published three poetry collections at roughly ten-year intervals. She has also been an eminent, sometimes controversial, academic. Her poetry must have been a release from the stylistic and emotional restrictions of her academic work.

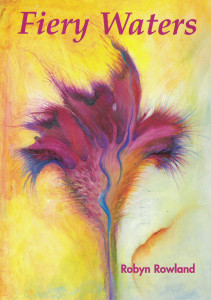

Fiery Waters, her new collection, is a leisurely and deeply felt progress across most aspects of a middle-aged woman’s life. Both sensual and sensuous, it is concerned with the ‘real world’, whether in apparently autobiographical poems of love and loss or in her more political poems against injustices here and overseas.

- Book 1 Title: The Sixth Swan

- Book 1 Biblio: Five Islands Press, $16.45 pb, 116pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Title: Fiery Waters

- Book 2 Biblio: Five Islands Press, $16.45 pb, 89pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

The third section is mainly a lament for the departed lover. It is in a poem such as ‘A Stretch of Time’ that one sees the virtues and some possible limitations of Rowland’s approach. The poem begins with a Neruda-like catalogue of all the things that will be the case when ‘I will awake one morning / and you won’t be the first thought / on my mind’. It is a poem written with great personal intensity, but readers may differ as to whether or not the poet tips over into sentimentality at the end: ‘I watch the steady ageing of my skin / and remember yours still smooth / and silky taut. /And I know it. / But for now / you are just gone. / And I miss you.’

In case this makes Rowland sound too self-absorbed, readers should also consult the section ‘Bevelled Edges’, where she deals tellingly with a range of injustices around the world, always bringing out their human dimensions rather than simply wringing her hands. The poems cover stolen Aboriginal children, the ‘disappeared’ in Argentina, the killing of women and children in East Timor after the plebiscite, cruelty to animals (an elephant in this case), gang rape, female genital mutilation, and the suffering of women during the Greek civil war.

The last two sections of the book open light-heartedly enough with ‘Men Only’, a very female meditation about just what it is that men do when they head off from a BYO restaurant to find a bottle shop. By the end of the collection, however, we are back in more harrowing territory with an extensive account of the 1983 Ash Wednesday bushfires and four poems dealing with the poet’s brush with breast cancer. The book ends affirmatively with ‘Alone and in Darkness’, inspired by the Sufi poet Hafiz. Here are its last three lines: ‘Feeling fear, give it some rightful place. / Feeling calmness shared, and some kind of grace. / Travel with me now like this. Courage sweetly comes.’

Rowland is hard to slot into the frame of contemporary Australian poetry. She holds no obvious stylistic or literary or political allegiance. She has had a major career elsewhere. It is probably best to regard her simply as a talented woman writing directly and courageously out of her own experiences – and taking the risks (including the occasional cliché and sentimental line) that this seems to involve.

Diane Fahey is a very different kind of poet. In The Sixth Swan, her seventh collection, readers will detect nothing of the author’s private life. They will, however, form a strong sense of her personality: introspective, sardonic, drawn to the mystical, and with a love of language for its own sake. And all this will come simply from her retelling of stories first written down almost two hundred years ago, and probably composed centuries before that.

In this book and most of her previous ones, Fahey works in a genre that is popular with contemporary Australian women poets. She is one of its most accomplished practitioners (if not quite its creator). The art is to take an old myth or story (the Greeks are a good source) and give it a contemporary, usually feminist, spin. The dangers here are considerable, however. The archetypal mysteries of the myths may be trivialised for a quick joke. The original myth may be too obscure for most readers. Sometimes, too, the ultra-contemporary slang may sound too clever by half.

Fortunately, Diane Fahey in The Sixth Swan, avoids most of these traps most of the time. Some of the Grimms’ fairy stories will be unknown to many readers, but Fahey overcomes this by printing bald summaries at the back of the book. The contrast between the flatness of these outlines and the language of the poetry is instructive and more than justifies Fahey’s rewriting them in her own manner.

In most of the poems, Fahey adopts a new angle on the story by employing a monologue or series of monologues to ‘update’ the story’s eternal point about human nature. In others, less convincingly, Fahey simply retells the story in her own words. Many of the poems, for instance ‘Marriage’ and the title poem, are impressive feats of social observation or pure imagination. In ‘Marriage’, the queen, who once could see everything in her kingdom, has married the suitor who successfully hid from her, and now ‘The only glass left in the palace // is in the spectacles he wears, / these autumn days, for reading. / Mostly, life is peaceful: the fact / that she doesn’t know something // he does know is they’re both aware – / what makes their union possible. / And it can go on for a lifetime. / All he has to do is keep his nerve.’

In the title poem, Fahey evokes just as effectively the almost opposite feelings of a young man metamorphosed back to humanity from swanhood but who, due to a slightly imperfect spell, still has a wing instead of his left arm: ‘He climbs the steps of the tower. It’s midnight. / The sky is a page of stars he can’t write on, / a compendium of invincible memories.’

Fahey and her colleagues are on to something with their retellings. Perhaps this is what we have always done, updating our myths to renew their relevance. That’s why poets and scholars keep translating The Iliad and The Divine Comedy. It’s an interesting question, though, whether or not the Jungian depths of the Brothers Grimm are as profound or congenial to the rewriting process as some of the other myths Fahey has used. One suspects that Fahey may be nearing the end of the line in The Sixth Swan, and that her next book will move into a more direct and personal engagement with our contemporary world, which is not to say that her present poems do not have much to tell us.

Comments powered by CComment