- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Strict Logic and High Technique

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Owen Dixon joined the Melbourne bar in 1911. By 1918 he was among its leaders, with the young R.G. Menzies as his pupil (and future lifelong friend). In 1926, five months as an acting Supreme Court judge convinced him ‘that I would never be a judge’; but in January 1929 he accepted an appointment to the High Court. There he would stay for thirty-five years – almost from the beginning as the Court’s undoubted intellectual leader, and from 1952 to 1964 as Chief Justice. He is commonly regarded as the twentieth century’s greatest Australian judge, and often as its greatest judge in the English-speaking world. His biography is long overdue.

Australian judicial biographies are rare. Mostly they deal with men whose judicial work was only one phase in a controversial political career. Biographers without legal training have sometimes uncomfortably skirted the edges of the judicial material; but, for Dixon, no such skirting is possible. In this splendid biography, Philip Ayres has risen to the challenge.

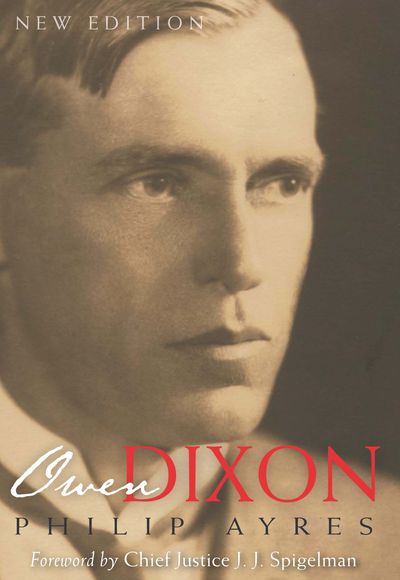

- Book 1 Title: Owen Dixon

- Book 1 Biblio: Miegunyah Press, $65 hb, 420 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

The focus is not only judicial. During World War II, Dixon chaired an ever-increasing number of government committees, including the Central Wool Committee. From May 1942 to October 1944 he was ‘Envoy Extraordinary’ to the Roosevelt White House, smoothing away the irritation of US political and military advisers at Australia’s constant demands for support. There he formed lasting friendships. Dean Acheson (later Secretary of State) expressed ‘complete trust and confidence’ in his ‘disinterestedness, wisdom and integrity’; General George Marshall found him ‘the most perceptive and understanding’ of Allied spokesmen. His wartime reputation and contacts led to his selection in 1950, by the UN Security Council, for a frustrating five-month attempt to mediate the Kashmir dispute between India and Pakistan.

The wartime committee work, the Washington mission and the Kashmir mediation each receive a separate chapter in Ayres’s biography, and add to the picture of an extraordinarily talented and complex man. Though Dixon professed to despise political life, and held himself strictly aloof from it, he was clearly fascinated by it; and despite his judicial preoccupation with what he called ‘basal principle’, his immediate rapport with soldiers such as Marshall depended on his pragmatism, scientific and technical curiosity, and scrupulous attention to detail.

Ayres’s narrative is enriched by anecdotes and personal recollections from Dixon’s former associates and others, and even more by Dixon’s personal diaries for 1935–65 (and two brief earlier periods). While the reminiscences dwell on Dixon’s infectious humour and spontaneous laughter, the diaries reveal a state of chronic depression and melancholia, deep unhappiness as a judge and contempt for most of his colleagues. His old-fashioned courtesy and personal gentleness are remembered as a lack of arrogance; but, in his diary entries, he showed no doubt about his own superiority, and no inhibitions in saying so. (Perhaps, of course, he was only letting off steam and indulging his sardonic humour.)

In Dixon’s family background, there may well have been reasons for chronic depression. His maternal grandfather died at thirty-seven of delirium tremens, after twice committing his wife to mental asylums. Dixon’s father, after failing at the bar because of deafness, had increasingly taken to drink; often, as a young barrister, Dixon had to stay home all day (or up all night) to look after him. Dixon’s daughters were both ‘regular, charming people’, but both his sons had difficulty adjusting to everyday life. He coped with their troubles lovingly and spoke of them proudly, but they must have caused him anxiety. In 1939 he took them on a five-month visit to England, seeking medical treatment for the older boy, Franklin; this trip, too, has a chapter in Ayres’s book. The treatment of family difficulties is candid, but admirably discreet and delicate, sometimes to the point of ellipsis.

A passionate Anglophile, Dixon had the prejudices of his generation. In London in 1939, a demonstration of television seemed to him to foreshadow ‘another means of debasing public taste & destroying standards’. On an earlier trip, in 1924, he sought out the ship’s smoking room but was ‘horrified to find women and Italians with a gramophone’. In 1943 he told a Tennessee audience that Australia was ‘a southern stronghold of the white race’; ‘the aboriginal native’ was a Stone Age relic doomed by advancing civilisation. In India, he found ‘such a lack of understanding among the people of the advantages of progress that it looks hopeless’; the experience taught him ‘how utterly impossible it is for us to relax the White Australia policy’. In 1950 he found the United Nations ‘full of visionaries, otherwise crackpots’, with ‘a huge staff, all of whom pursue fruitless ends and many of whom pass idle lives’.

Ayres allows these attitudes to speak for themselves. Only as to Dixon’s apparent anti-Semitism does he offer a defence or explanation: given a stereotype of Jewishness as ‘something “oriental” or Levantine’, Dixon tended to notice ‘those examples that confirmed his expectations’. Thus, in 1939, as he steered his son around the London eye specialists, he was quick to stigmatise those who seemed ‘Jewish’; but when one of them later moved to Australia, she became a much-admired friend. The explanation is persuasive: the most enduring of Dixon’s Washington friendships was with Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter; and in 1957 Dixon wrote that he had never expected ‘to find myself in such full sympathy with the Jews in Palestine’.

The judicial chapters refer to some ninety of Dixon’s judgments – a tiny sample, but, on the whole, a representative one. Lawyers will find some pleasing inclusions and some disappointing omissions; not all of us will have the same list. We are told of Dixon’s increasing discomfort in the 1950s with appeals to the Privy Council, but not of his extraordinary role in 1925 in sending Pirrie v McFarlane to the Privy Council despite its removal into the High Court. (Ayres does note that, as a barrister, Dixon ‘was not averse to impudent devices’.) He insists that Dixon ‘gave full weight’ to federal supremacy under section 109 of the Constitution; but omits Dixon’s classic exposition in Ex parte McLean (1930) of how section 109 works. He outlines Dixon’s decisive role in the Melbourne Corporation Case (1947), establishing a limited State immunity from Commonwealth interference; and also his (‘controversial’) insistence in the Cigamatic Case (1962) on an area of Commonwealth immunity from State interference. But the two doctrines are twice presented as ‘mutual’, though in Melbourne Corporation Dixon insisted that ‘these are two quite different questions … affected by considerations that are not the same’.

We are shown how Dixon developed these doctrines by clawing back ‘exceptions’ to the Engineers’ Case (1920), which abolished an earlier doctrine of reciprocal governmental immunities. In stating Dixon’s position as at 1937, Ayres is careful not to ‘overstate the matter’, acknowledging that Dixon saw Engineers as ‘a valid check’ on earlier ‘excesses’. Yet, when Engineers itself first appears in Ayres’s chronological narrative, he appears to lament its ‘centralism’ in rhetorically loaded terms. Again, from the vantage point of 1937, Ayres harks back to Dixon’s first restatement of Engineers in the ARU Case (1930), but gives no account of how Dixon took control of that case, repeatedly redirecting the argument to make room for his restatement. Other relevant cases are summarised so elliptically as to be misleading: for example, the discussion in Farley’s Case (1940) of limited Commonwealth power over the States is explained without mention of Dixon’s concern with the limits of State power over the Commonwealth.

At times, Ayres is too concerned to insist that Dixon’s doctrines are ‘apolitical’. Ironically, he is also sometimes too ready to introduce a political tone. He indignantly rejects any imputation that Dixon’s view of the constitutional freedom of interstate trade could promote the ideology of a laissez-faire market, insisting that any criticism of Dixon’s theory must reflect the ‘pragmatic, regulatory’ bias found ‘in government, and sometimes in the courts and law schools’. That the issue is more complex than this is sufficiently shown by Chapman v Suttie (1962), where Dixon (dissenting from the majority’s application of his own theory) insisted that gun controls should not be struck down unless there was ‘clear proof’ that they affected interstate trade. He then took an extraordinarily narrow view of the evidence to show that no interstate element had been conclusively proven. Ayres notes the case, but misses the point.

What makes such observations important is the difficulty of doing full justice to Dixon’s judicial method. On becoming Chief Justice in 1952, Dixon made a famous plea for ‘strict and complete legalism’. His meaning has often been mis-construed: like Jane Austen, Dixon has often been ill-served by his admirers.

Fortunately, Ayres is aware of the problem. He acknowledges Dixon’s capacity to ‘develop’ the law – for example, patent law in the National Research Development Case (1959), or torts in Commissioner of Railways v Cardy (1960). He knows that Dixon’s ‘legalism’ included his belief in the common law ‘as an ultimate constitutional foundation’. He recognises the distinction between legalism and ‘literalism’, and the subtlety of Dixon’s handling of precedent. He works carefully through the text of Dixon’s 1955 lecture ‘Concerning Judicial Method’, which insisted on the importance of ‘strict logic and high technique’, and rejected both the hubris of ‘the conscious judicial innovator’ and the ‘false doctrine’ of judicial impotence. Arguably, Ayres gives too much weight to the former rejection and too little to the latter. Yet he recognises the potential for misunderstandings. In a letter to Frankfurter, Dixon explained that the line about ‘judicial innovators’ was aimed at their English contemporary, Lord Denning; yet he also reported wryly that Denning had written ‘saying he completely agreed with everything I wrote’.

In an epilogue, Ayres returns to these issues. He assembles an intricate list of Dixonian qualities balancing rigorous legal technique with ‘deep understanding of human nature’, ‘independence of thought’ and ability to give principled effect to ‘changing conceptions of justice and convenience’. The balance is judiciously struck.

Regrettably, the careful discussion of Dixon’s 1952 plea for ‘legalism’ is marred by an unnecessary attack on the ‘creativity’ of the Mason Court ‘in the 1980s and early 1990s’. Repeated on the final page, the attack is a gratuitous and offensive blemish on an otherwise impressive achievement.

Comments powered by CComment