- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The Wilder Shores

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Art is divided into three parts – at least for amateur painters who ask, when they begin acquaintance, ‘Do you do abstract, impressionist or surrealist art?’ Of these, surrealism has the strongest interest for a mass audience, and the deepest penetration into popular culture. When it was new, surrealism was quickly appropriated into commercial and advertising art. Today, commercial cinema is awash with some of surrealism’s youthful political idealism, but more with its fantasies of shock-horror and sex.

Surrealist literature never came to much. The artists took over. If Picasso was the greatest twentieth-century artist, his surrealist paintings from the 1920s onwards might be his own best work. Remember how the best exhibition ever produced in Australia, Surrealism: Revolution by Night (National Gallery of Australia 1993, by Michael Lloyd, Ted Gott and Christopher Chapman), showcased Picasso ahead of Miró, Dalí, Magritte and Ernst. And the star of the Australian component of the exhibition was James Gleeson.

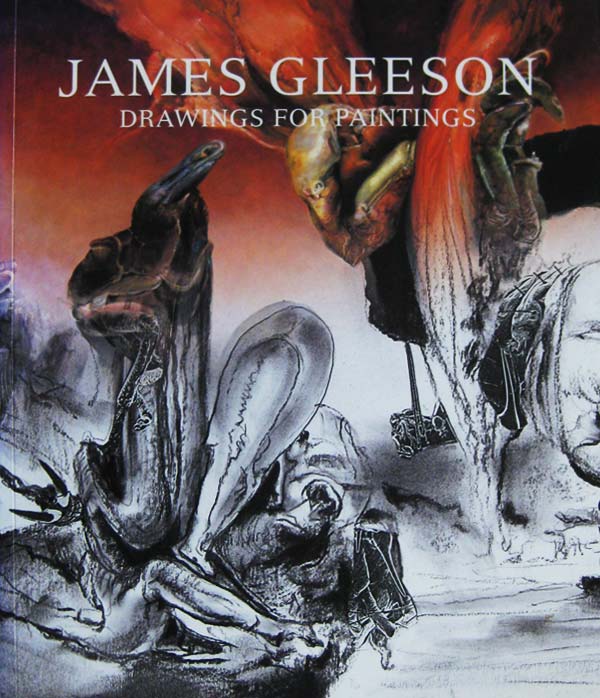

- Book 1 Title: James Gleeson

- Book 1 Subtitle: Drawings for paintings

- Book 1 Biblio: Art Gallery of NSW, $60 hb, 128 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Aged eighty-seven – and with a big show of new paintings last month at Watters Gallery, Sydney – Gleeson, now that Nolan, Boyd, Tucker and Klippel are gone, must be our only surviving artist formed by 1930s politics, Freudianism and surrealist poetry. His first exhibited works, in 1938, were Daliesque. They were promptly reproduced in the local art magazines. In 1940 Art in Australia published his essay ‘What is surrealism?’, and in 1941 the NGV acquired his seashore painting We inhabit the corrosive littoral of habit.

Seashores were a recurrent theme in Dalí’s art. They were personal memories of childhood play on the Spanish Costa Brava, or of private places for sexual congress, but also a general statement of wonder at planet Earth’s most fertile zone for biological geological and meteorological evolution and transformation. Similarly, Gleeson, who grew up at Gosford, spent much of his childhood exploring anemones and shellfish in rockpools at Terrigal; he described a 1951 painting of a drowned Phoenician sailor as suffering a ‘sea-change; he has become coral and sea growths, pearls and sponge’. Gleeson later took holidays at Peregian near Noosa, and his art for the past twenty years has returned to the shore in an astonishing series of over 300 large, two-metre canvases of strange coasts. There are no humans in, say, Infested dune, La Costa Metamorfica or Alert on a quickened coast. Rocks, clouds and shadows, polyps, cysts, bones, indeterminate viscera and occasional foetuses or eyes wave and surge in a primordial stew. The world is always, it would seem, at the point of quickening into new forms of life.

The size, the sensuous paint-handling, the atmospherics of Gleeson’s late canvases are, however, a conscious departure from his first dry, hard-edged Dalinean style; they instead acknowledge the sublimity of J.M.W. Turner, most obviously in The arrival of implacable gifts (1985). There an upside-down appropriation of Turner’s storm-tossed, sinking Slave ship (1840) inhabits the sky, dropping malign, cargo-cult mystery parcels onto a wild shore, while a severed self-portrait head of the mild, bespectacled, Sydney-suburban artist watches serenely from behind a cephalopod-rock. We always come out of our wildest dreams unharmed. Lie back and enjoy the unfamiliar, the unpredictable; the horrid might even turn out benign. Do not inhabit a world filled with corrosive over-familiar habits. Dreams are good for our psychic health.

Dreams were adored by anti-rational surrealism. So Gleeson took up the custom of a bedside pad to capture his dreams, to make them into paintings. Sometimes a fully developed composition drawing, complete with title, emerged on waking. An exceptionally vivid trans-action from the night was Crater with revenant (1966), painted direct to canvas, without a preparatory drawing.

This we learn from the Art Gallery of NSW’s wonderful exhibition book of Gleeson’s drawings for paintings. We already had Lou Klepac’s James Gleeson: Landscape out of Nature (1987), in which thirty-eight of the late paintings were paired with a preparatory charcoal drawing. There it was interesting to note the variations, more or fewer teeth in Aurora dentata, hardening or softening of vertebrae, the addition of a veined hammerhead cloud to Fossilized storm of the Triassic period, and the self-portrait head in Implacable gifts. The new book gives drawings for sixty paintings, of all periods, 1938-2000, and sometimes as many as seven drawings for a single painting. With detailed information on each work, it is a rich and generous feast.

Figures appeared in all the early work (except the brief phase of abstract expressionist pourings around 1958). Besides a few appropriations of figures from Renaissance and Victorian art, there is at least one traditionally beautiful body, that of the Sydney poet Roland Robinson, who posed for two life-class figures in the painting Fête champêtre, a lethal regulation (1944). But most figures look different from the usual conventions, and we wonder who they might be.

The eroded, empty head that looks out at us in 1940 from We inhabit the corrosive littoral of habit was, says Gleeson, ‘not a portrait. Just a face, possibly taken from a magazine.’

Further, Hendrik Kolenberg and Anne Ryan tell us that male figures in Gleeson’s paintings of the 1950s and 1960s – a phase more symbolist than surrealist – were generally based on photographs in physical-culture magazines, concerned with health and strength. So the poses, unfamiliar in high art, come from the competitive subculture of bodybuilding, in which photographs are styled merely to display muscular development, rather than to signify states such as courage, fear, grief or ecstasy. These paintings were plainly homoerotic, yet the figures seemed strangely unsexy. Now we know why.

Further still, we learn that Frank O’Keefe, Gleeson’s partner since 1949, modelled for figures in Italy (1951), The crucifixion (1952) and the already-mentioned Crater with revenant (1966). His body resembles a bodybuilder’s, so perhaps the nude gym rats uneasily appropriated into the myth and dream paintings are substitutes for Frank. We begin to appreciate this phase better; the paintings gain warmth. And, in The crucifixion, Frank appears for once as a good-sized fore-ground figure, upon whom the gaze is distinctly tender.

Cinema or cinema advertisements might be an earlier source. Now that we are alerted to appropriation, we can wonder whether, before he settled on physical-culture sources, Gleeson pinched sexpot faces from Cocteau’s surrealist movies. A case in point is Sea wrack involving the heads of Tristan and Isolde (1947). These elaborately cut-and-pasted compositions of appropriated imagery could have been a conscious device in their day, like musical dissonance. Now they look strangely up to date, like postmodern digital imaging. (And this new book notes that its ‘Cover illustrations have been digitally merged [painting with drawing], with the permission of the artist.’) Yet some might still prefer a 1944 anti-war masterpiece, The sower, harmoniously based on a single figure of agricultural labour by J.-F. Millet but warped and dislocated into bleak dismay by the time’s immense, mad genocides.

Renée Free’s book James Gleeson: Images from the Shadows (1993, expanded 1996) is a reworking of the material for a retrospective exhibition that did not take place at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. She offered a focused Jungian interpretation of Gleeson’s art, based on the absence of a father, dead when James was three. The National Gallery of Victoria has scheduled a full retrospective for 2006, when Gleeson will be ninety. Let’s hope the promised exhibition includes some of these drawings, many of which are gifts to AGNSW from Frank O’Keefe, and that its interpretation discusses not only the absence of a father but also the presence of love.

Comments powered by CComment