- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: An Intricate Dance

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In a number of guises, the question ‘why’ reverberated throughout my reading of Whatever the Gods Do: A Memoir. This book opens with Patti Miller describing her sadness at the departure of ten-year-old Theo, who is leaving for Melbourne to live with his father. We soon discover that the author has been Theo’s substitute mother for the past seven years since the tragic death of Dina, his birth mother and Miller’s friend. Dina suffered a brain haemorrhage when Theo was two years old. She spent thirteen months in a virtually immobile state before her death at thirty-eight. Why the vibrant, attractive Dina should have been struck down when she had so much to live for is a legitimate question, but, of course, an unanswerable one. Why Miller should choose to write about her own life through this incident is also worth asking. Few are more qualified than Miller to address the reasons for, and benefits of, life-writing: she has run ‘life stories’ workshops around the country for more than ten years. In her bestselling manual Writing Your Life: A journey of discovery (1994), she identifies various motivations for, and rewards of, life-writing, including healing and self-understanding, recording family and social history for future generations, remembering happiness and sharing one’s wisdom.

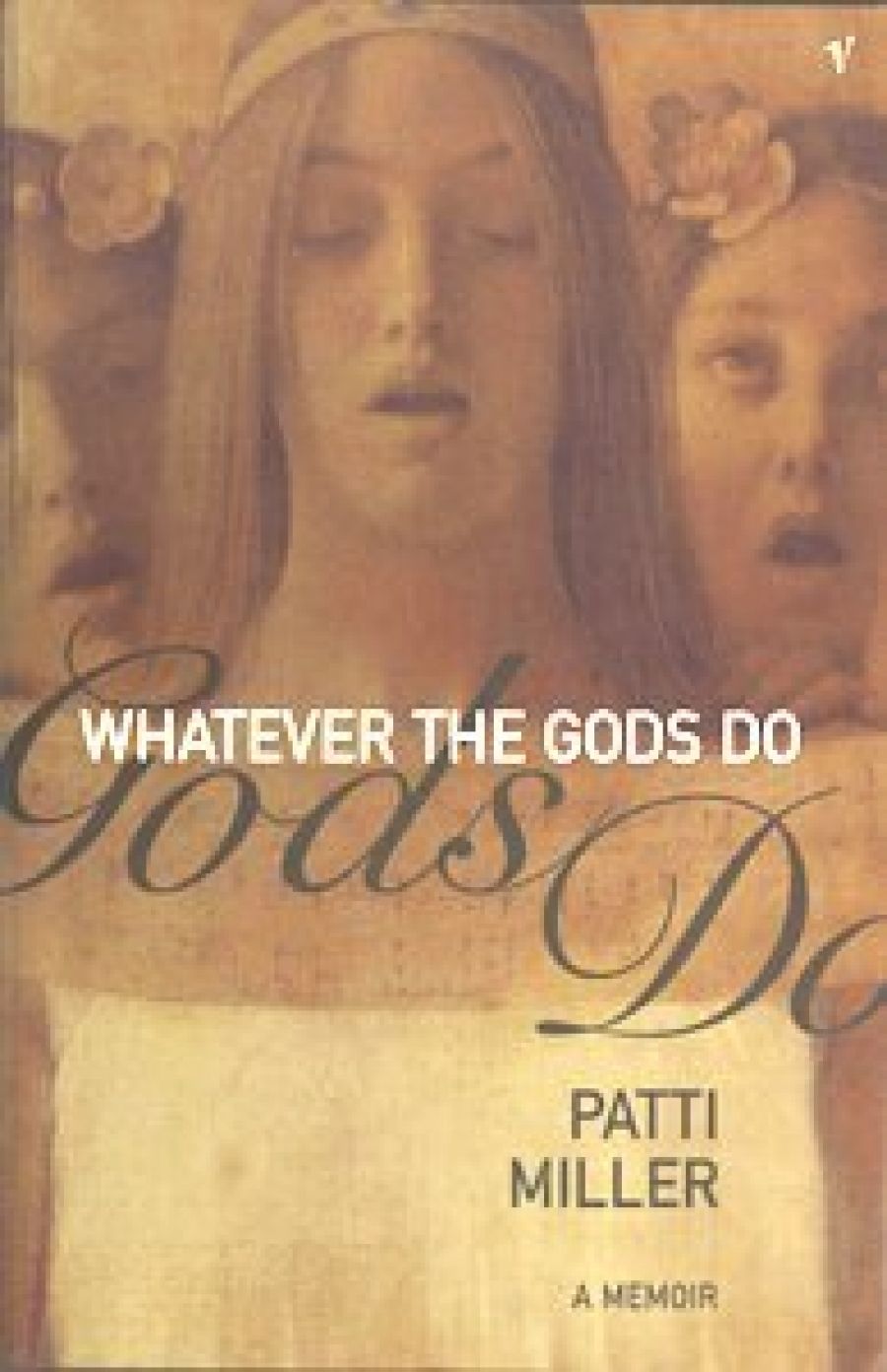

- Book 1 Title: Whatever the Gods do

- Book 1 Subtitle: A memoir

- Book 1 Biblio: Vintage, $21.95pb, 227pp

Clearly, Miller could have various personal reasons for writing about recent events in her life. In the current publishing climate, many such accounts of relatively ordinary lives are finding publishers and willing readers. Nor is Miller alone in ruminating in print upon a journey into what Susan Sontag termed ‘the kingdom of the ill’. Some intimate memoirs of sickness and death have been written in the first person, such as Robert McCrum’s My Year Off: Rediscovering life after stroke (1998) or Inga Clendinnen’s Tiger’s Eye (2000). Others have been written by family members, such as Linda Grant’s Remind Me Who I Am, Again (1998) or, closer to home, Peter Rose’s Rose Boys (2001). Most recently, Sonia Orchard published an exquisitely written account of her best friend Emma’s doomed battle with cancer, Something More Wonderful (2003), which has many parallels with Dina’s story.

The question I find harder to answer, therefore, is not why Miller has published an account of a friend’s protracted death, but why she has done so in such a fragmentary and, frankly, irritating form. While Dina’s illness and death, and the roles they ultimately provided for Patti in relation to Theo, are central to Miller’s memoir, this narrative thread is constantly interrupted by episodes from her own life. She interweaves reflections on her longing to learn to sing and related symbolic associations (birdsong and drought), excruciating descriptions of her singing lessons, details of her loss of desire and menstruation (her own ‘drought’), flashbacks to her childhood, accounts of her dreams, shards from other people’s stories told in her life-writing classes, and self-conscious, present-tense reflections on her struggles with writing this memoir. Presented in short, disjointed segments, this excessive fracturing means that the book lacks cohesion. This detracts from the most interesting aspect of the book: how Dina’s life was halted and how her husband, friends, and child responded to this situation. Miller’s own life should simply have been reflected through this story, rather than being brought sharply into focus. When the spotlight shines only on Miller, my interest waned.

It’s not that Miller fails to produce compelling prose: parts of her memoir are beautifully rendered and perceptively evoked. When she first visits Dina after she has emerged from her post-haemorrhage coma, Miller comments: ‘There was a coldness around her, a miasma of hopelessness. It wasn’t so much in her face – she could not move enough of her facial muscles to indicate feeling – but a misery so profound it emanated from her. Her life had blown up from the inside without warning and there was no redemption anywhere in sight.’ Similarly, Miller’s descriptions of the growing intimacy between Theo and herself as she fills in for his hospital-bound and helpless mother hum with poignancy. They perform an intricate dance as this little boy, pining for a mother’s physical presence, reaches out to this alternative maternal figure, while establishing rules of engagement. The first time he slyly kisses Miller, he adds, ‘My mummy is sick’. As Miller records: ‘For weeks, each kiss was followed by a statement about his mother. He was only a chubby toddler, but he understood loyalty and knew exactly the correct rhythm and pace for forming a new attachment.’ On another occasion, Miller finds herself being deliberately introduced by Theo to familiar adults and certain children at childcare, coming to the realisation that this was a form of ‘adoption’ ceremony. Throughout, Miller is open and brutally honest about how her blossoming relationship with Theo must have seemed to Dina. Miller feels like a ‘usurper’ and worries that one day Theo will realise ‘that his loss has been my gain’.

The intricate patterns woven into these descriptions of human interactions do, however, serve to highlight the banality of some of Miller’s reflections, dreams, and her singing lessons, which she has chosen to bear the symbolic weight of this book. I suspect that Miller has learnt some of her Writing Your Life lessons too well. In this manual, she emphasises the importance of symbolic imagery as a key to memory, recommending free association across random memories. Moreover, while her writing handbook recognises the importance of structure, she advises: ‘Structure created before the fact of writing is artificial and limiting … I like to leave a discussion of structure until plenty of writing has been done.’ These comments provide insight into Whatever’s failings: Miller has followed her tips for sparking the fuse of memory and stimulating the flow of writing, but life-writing still requires crafting, sifting, and artful remembering before publication.

Comments powered by CComment