- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Children's and Young Adult Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Cultural Clashes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

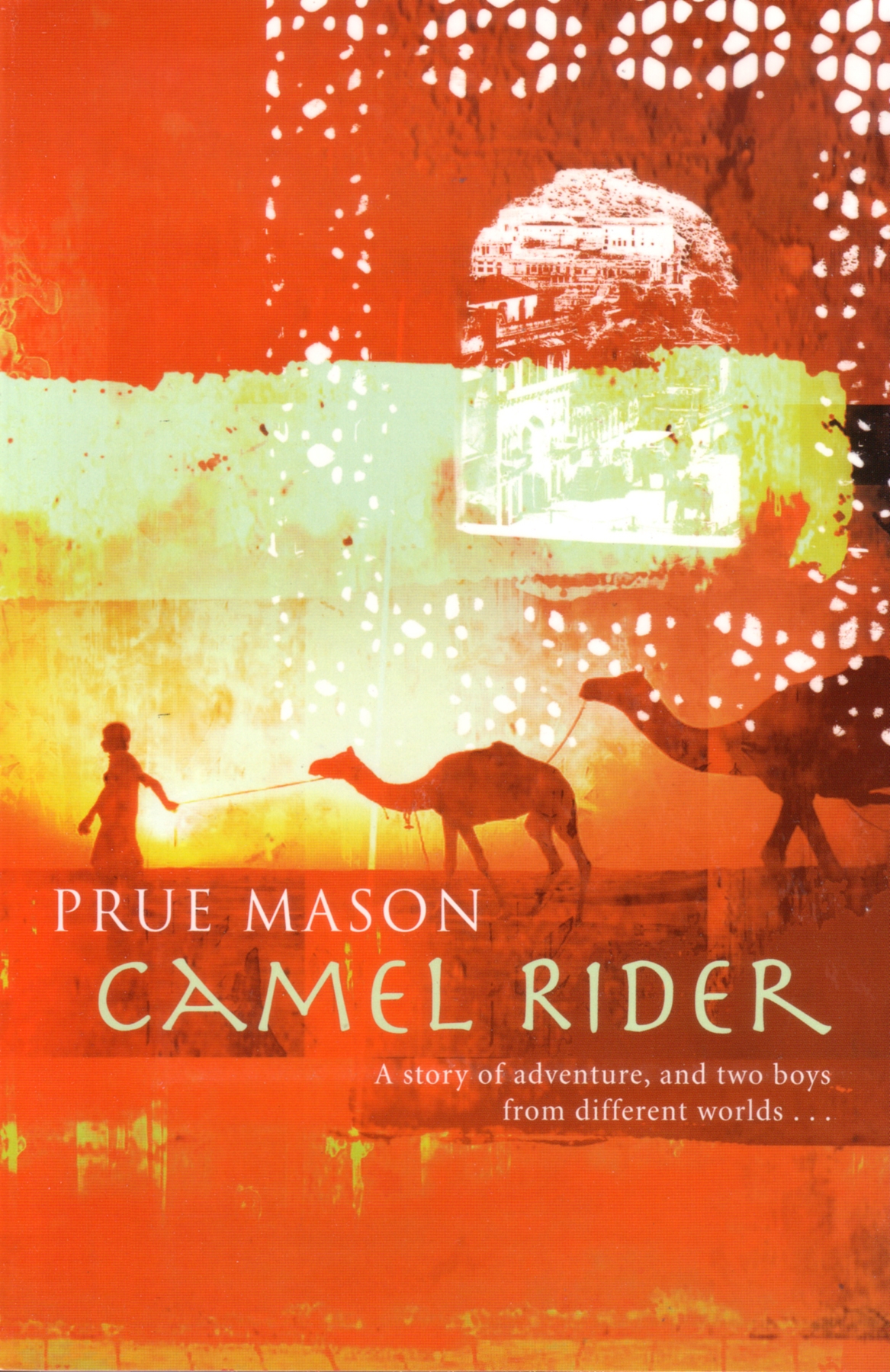

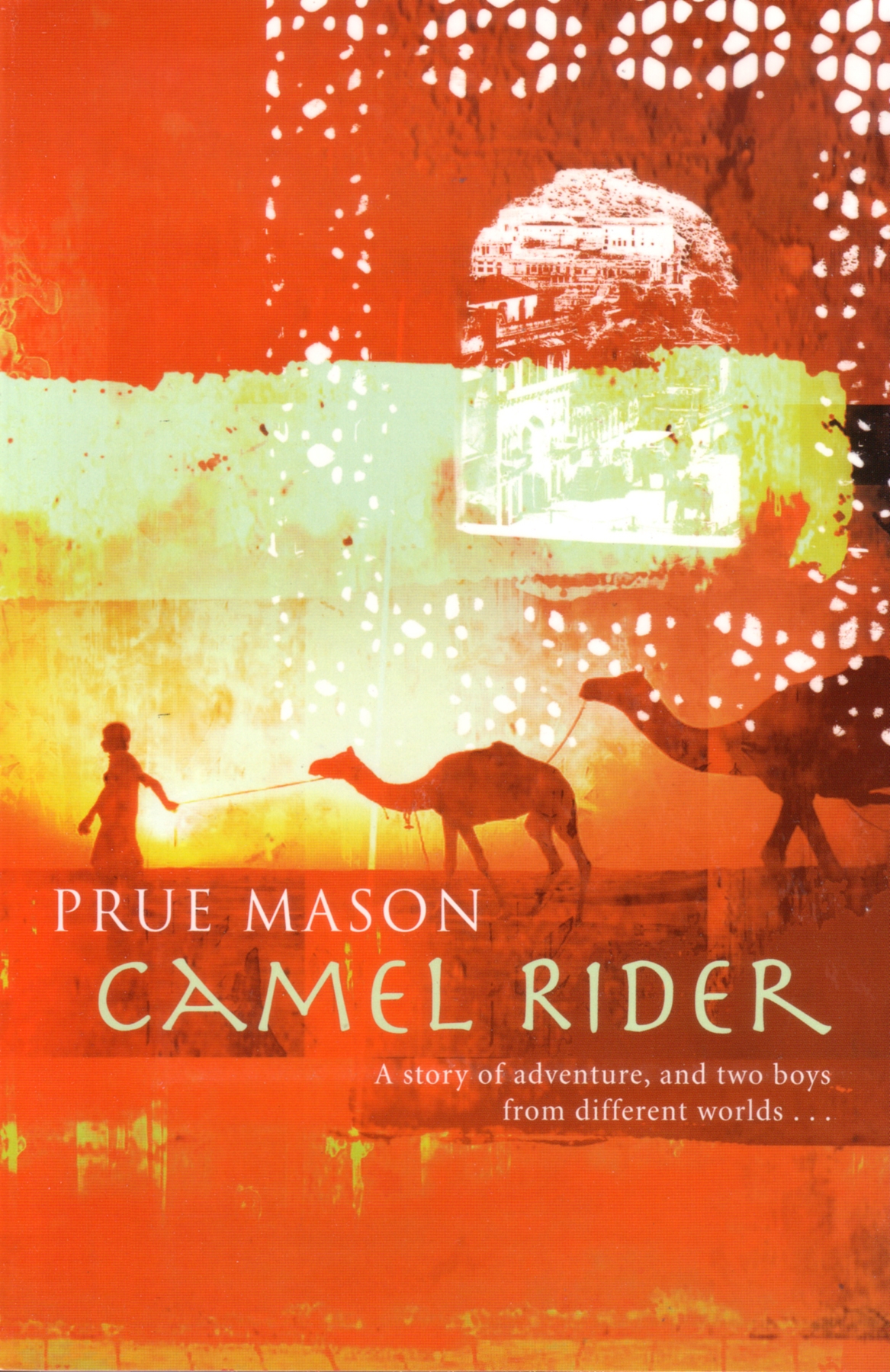

Camel Rider is, according to the Penguin press release, the story of a young American boy living in the Middle East. When war breaks out, the release goes on, the boy is left behind as his family flees to safety. He befriends a young Arab boy, who has been kidnapped and taken to the desert as a camel jockey. Actually, no. Camel Rider is the story of a young Australian boy, Adam, living in the Middle East. When the city is invaded, his family does not flee. His father, a pilot, is away on a four-day trip (with Adam’s passport tucked unknowingly in his flight bag); his mother is on her way to Melbourne alone simply because, without a passport, Adam is unable to travel with her. In the desert, Adam meets a young Bangladeshi boy, who has not been kidnapped but rather sold to slave traders. Should it matter that a press release has it so wrong? I think it does.

- Book 1 Title: The Silver Donkey

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $24.95hb, 191pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Title: Camel Rider

- Book 2 Biblio: Penguin, $16.95pb, 172pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 3 Title: The Last Muster

- Book 3 Biblio: Scholastic, $16.95pb, 170pp

- Book 3 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 3 Cover (800 x 1200):

Through Adam and Walid, writer Prue Mason explores, on a micro-level, the complexity of the Middle Eastern conflict. The boys, products of their elders’ prejudiced stories, come together with an inbred mistrust and wariness of each other. But as they head deeper into the desert, it soon becomes obvious to both boys that they must overcome these cultural differences in order to survive. What follows is an action-packed adventure. Apart from the dangers of the brutal desert itself, the boys are chased, shot at and kidnapped. They survive a car crash, heatstroke and an all-night camel trek. They endure hunger and thirst and – the worst-case scenario for some – a mobile phone with a flat battery. Gradually, a genuine friendship develops.

On any meaningful journey, characters must evolve and grow. While Adam does redeem himself during the ordeal (this is a boy who lives in a Muslim country but complains bitterly about the daily calls to prayer, and who smugly dismisses his messy bedroom, knowing that the Indian maid will clean it), it is Walid who must sacrifice the most. He steals a car and a camel, and forgoes prayers – actions that sit uncomfortably with his Muslim faith.

Mason, who has lived and worked in the United Arab Emirates, has an intimate knowledge of the local people, language and culture. She wrote Camel Rider to bring attention to the plight of young boys sold into camel racing in the Middle East. I think she also brings to light another phenomenon – that of the precociously privileged and prejudiced expatriate child.

Another novel that deals with cultural differences is Leonie Norrington’s The Last Muster. As with her earlier novels, The Barrumbi Kids (2002) and The Spirit of Barrumbi (2003), Norrington sets this story in northern Australia. Her teenage protagonists, Shane, a white boy, and Red, a mixed-race Aboriginal girl, live on a cattle station in the Kimberley. When the children stumble across a wild stallion roaming the property, Shane is determined to tame it. The stallion’s appearance, and the ensuing journey that the children take to capture it, open old wounds and stir bitter secrets. Shane’s father, whose family settled the land nearly one hundred years earlier, is now only manager of the station. ‘The Company’ has bought him out, leaving him bitter and resentful. Lofty, Red’s grandfather, is the only Aborigine left on the station, the others having been forced to move on after the company takeover. Lofty has refused to leave his country, and continues to stay on with Red. While Shane’s father and Lofty have grown up together and developed a deep friendship, there are underlying tensions between the two.

When the Company decides to merge several stations in the area, Shane’s father is outraged that his family may be forced off the land. Norrington sensitively visits the issue of connection to country. While Lofty has deep spiritual links to the land, he does not consider that Shane’s father, a whitefella and outsider, could possibly have the same attachment. Shane and Red hatch a plan for Lofty to claim land rights, which may enable them access to parts of the property. However, Norrington does not provide a simplistic, happy-ever-after scenario. We sense that, as much as the children think they have found the perfect solution, Shane’s father will not be content to ‘squat’ out in the stone country, and it is unclear whether Red will be prepared to live a traditional life with her grandfather.

Having grown up on an Aboriginal community in the Northern Territory, Norrington writes with the confidence of one who knows the people and country well. She has created a distinct voice, merging English with Kriol. Her dialogue flows, so that sentences such as ‘Dad reckon, old time one Aboriginal man, wild man, name Pigeon, been killing people ...’, jarring when taken out of context, enhance the story.

Another story told beautifully is The Silver Donkey, Sonya Hartnett’s first novel for children. While much could be read into this story – the symbolism of the donkey for starters (stupidity, ignorance, idleness, or courage, loyalty, humility, depending on your culture of choice) – this is, for me, a tale about the age-old tradition of storytelling.

When two young girls find a soldier, blinded by the horrors of war, in the woods near their home, he becomes their delicious secret. He carries with him a tiny silver donkey, a good luck charm given to him by his brother. Over the next few days, as the soldier rests and the girls plan how to help him return home, he tells them stories. All are about donkeys – loyal, courageous and humble. Hartnett writes with a formality that sits well with the setting (early twentieth-century France), but this will not alienate her readers. Despite the soldier’s accounts of his horrific war, Hartnett recalls a time of innocence when children could wander alone into the woods, and when talking to a stranger wasn’t considered dangerous. It was also a time when something as simple as a tiny silver donkey could excite a child’s imagination. This is not a story with big issues but a gentle one depicting courage, loyalty and bravery – shown not just by the donkeys in the stories but the young girls, their brother and a friend as they help the soldier. It will resonate with children and adults of all ages.

Comments powered by CComment