- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Molony’s Paradox

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Luther’s Pine is a beautiful account of an old man’s encounter with his younger self. John Molony’s life has an iconic quality. His father fought on the Western Front during World War I, sustaining injury from mustard gas, before returning to marriage and settlement in the Mallee area of Western Victoria, close to Sea Lake. Sea Lake was also the home of John Shaw Neilsen. Young Molony, born in 1927, shared some of Neilsen’s ability to find beauty in an arid landscape: ‘in that poor country, no pauper was I.’

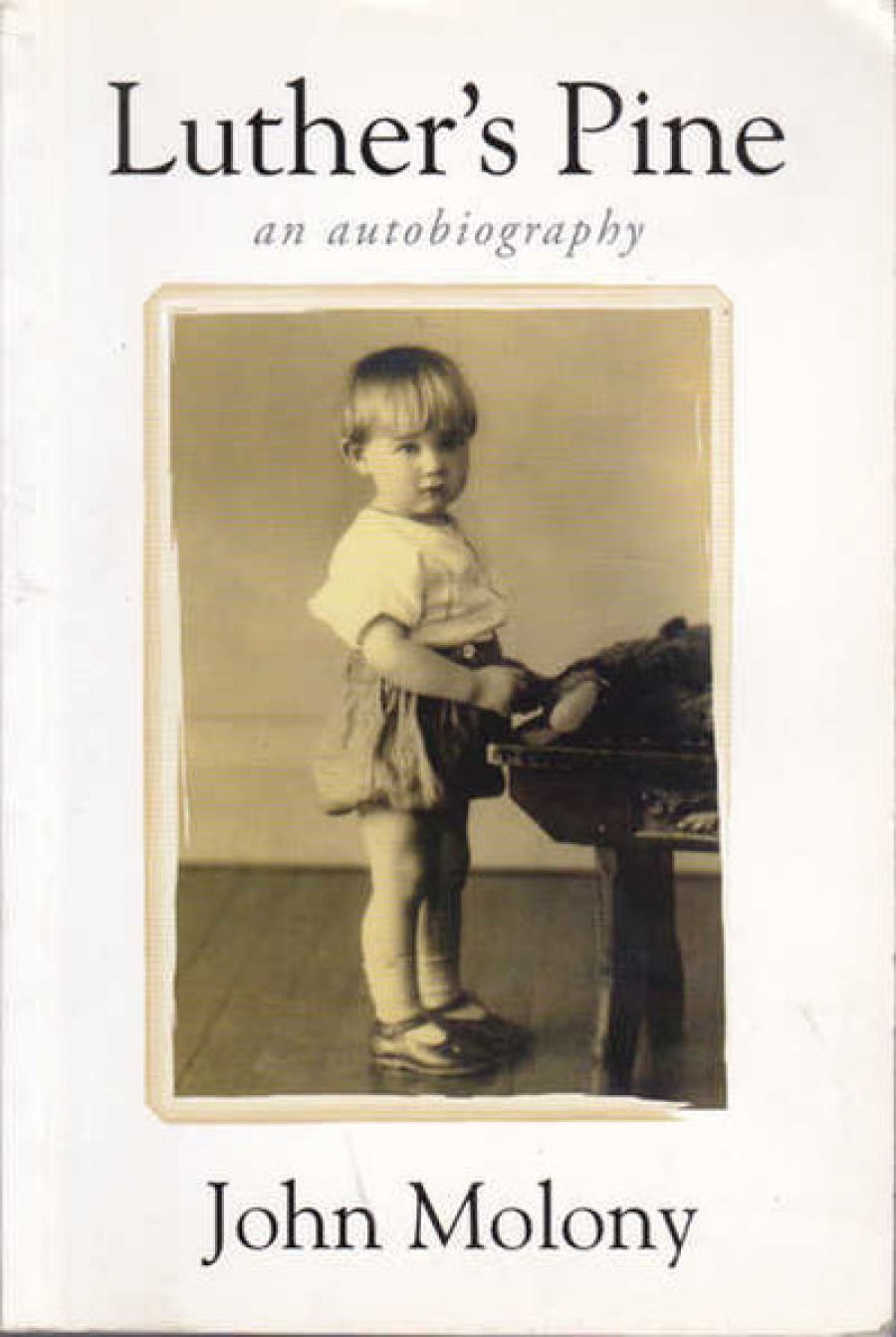

- Book 1 Title: Luther’s Pine

- Book 1 Subtitle: An autobiography

- Book 1 Biblio: Pandanus, $45 pb, 299 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Drought and depression made life on the land impossible; by the mid-1930s the family had relocated to Melbourne, where Molony’s father struggled, selling vacuum cleaners until managing to secure a job as a truck driver for a petrol company. Molony describes himself as a ‘nomad of the schools’, but, while a student at St Patrick’s College, Ballarat, he decided he would like to be a Catholic priest. It is this decision that sets up the most gripping part of Luther’s Pine. The book describes in great detail and colour the course of training Molony embarked upon in 1945 at the age of seventeen, first at the seminary that Archbishop Mannix had founded at Werribee, at that stage a town separate from Melbourne.

From 1947 onwards, Molony trained at the Propaganda Fide College in Rome. It was a considerable honour to be chosen to study in Rome; ‘Prop’, as it was generally known, was the liveliest part of the Catholic Ivy League. The college produced squadrons of bishops and archbishops. The book that first made Molony’s name as an historian, The Roman Mould of the Australian Catholic Church (1968), spelt out the impact of this training system on local Catholic communities in Australia.

Luther’s Pine pays warm tribute to a generation of Catholic leaders in Australia (Bede Heather and Frank Little among them) that worked long and hard to develop a vibrant church in Australia and then received very shabby treatment from their feudal overlords. That is not so much Molony’s story, although it is one that needs to be told. Molony knew these men as young idealists. He makes great reading out of the seemingly arcane minutiae of daily life at the college. He tells us what it is like to be far from home and feeling crook.

A deep sadness runs through this book. The story ends much too soon. I declare my interest as a friend of the author, and own that the last line of Luther’s Pine stopped me in my tracks and sent me back to reread the whole work. The book concludes the moment Molony says his first Mass: ‘Above Peter’s Tomb, in Rome on 21 December 1950 I was at last doing what my God had given me life for in Melbourne on 15 April 1927.’ Yet the back cover states that John Molony has a wife, four children and seven grandchildren. I was astonished that, given these happy circumstances, Molony would still describe himself as being brought into the world to say Mass. The closer you get to this book, the clearer it becomes that it derives much of its restless energy from this paradox.

Molony appears to live with unresolved issues, at least in relation to the church. He speaks of his admiration for the papacy as an institution. As he approaches ordination, his friend and mentor, Archbishop Simonds, makes it clear that he expects Molony to become a bishop himself. And at times, this autobiography does read like the memoirs of an archbishop. But Molony didn’t become a bishop. He left active ministry and married, a story that stands in the wings of this drama, where you can hear its feet shuffling impatiently. He describes two subsequent encounters with priests who had been important to him, one in Australia and one in Rome. On both occasions, Molony expresses gratitude that these august men would still want to be his friends. I found this hard to read. It seems to me that Molony never had more right to expect his friends to act as friends than when he left. It is almost as if he is apologising for causing hurt. A less generous man would point out that some apologies may well be owing to him.

Molony carries his grief with such dignity that at times I felt a lump in my throat. ln 1999 he returns as an old man to the seminary in Werribee, now open to the public, and stands on the very spot from which, aged nineteen, he was despatched to Rome, not to see his family for years on end. He recreates his time in Rome from letters that had been faithfully stored in a tin. By such means, the old writer enters into a rare intimacy with himself as a young person. Molony’s father hovers over much of what he writes like an absent god: ‘he rarely wrote to me during the long time I was away, but, when he did so, I treasured his every word.’ John learns after his father’s death that he had described one of John’s return letters as ‘just another bloody sermon’.

As much as I was embraced by and wrapped up in the humanity of this story, I was also alienated by much of its religious sensibility. The centre of Molony’s faith is the performance of Mass, something which, for him, takes place in church and for which you need special clothes and so on. He does not like the word Eucharist, a word that became familiar after Vatican II and that means the same as Mass but with a different nuance. For me, the Eucharist describes the whole of life. I, too, am a former priest. In some ways, I stopped being a priest so that I could celebrate the Eucharist, something that happens in my life when we give thanks around a family table. For me, what happens in church is simply the drawing of the intimate experience of the Eucharist into a broader context of community. John Molony sees it very differently. For him, Mass is an enclosed celebration from which he feels excluded. He pines. It is unjust and sad to see a man, with such a gift for reaching out to others, live with this pain.

Comments powered by CComment